Perspective on Risk - June 28, 2023 (Demographics Update)

Recent Observations; Some Implications; How Much Does Aging Really Hurt A Country? Climate Change Is A Wildcard; The World in 2075; ++Glastonbury 2023

It’s time to talk again about the third leg of my long-term view: demographics. This is perhaps the most knowable of the three drivers (demographic, technological change, globalization/decoupling)

For those new to the framework, I discussed the other drivers in these posts: I’m not going to rehash topics from the Sept. 16 PoR, so you may want to review that first (if you have any interest in the topic).

Demographics

Perspective on Risk - Sept. 16, 2022 (Demographics)

Technological Change

Perspective on Risk - Dec. 9, 2022 (Technology)

Perspective on Risk = Jan. 17, 2023 (Technology & Productivity)

Perspective on Risk Jan. 25, 2023 - Technology Implications

Globalization/Decoupling

Perspectives on Risk - Oct. 14, 2022 (Decoupling)

Perspective on Risk - Jan. 31, 2023 (Decoupling Update)

TL;DR

Here is the takeaway to put in your brain.

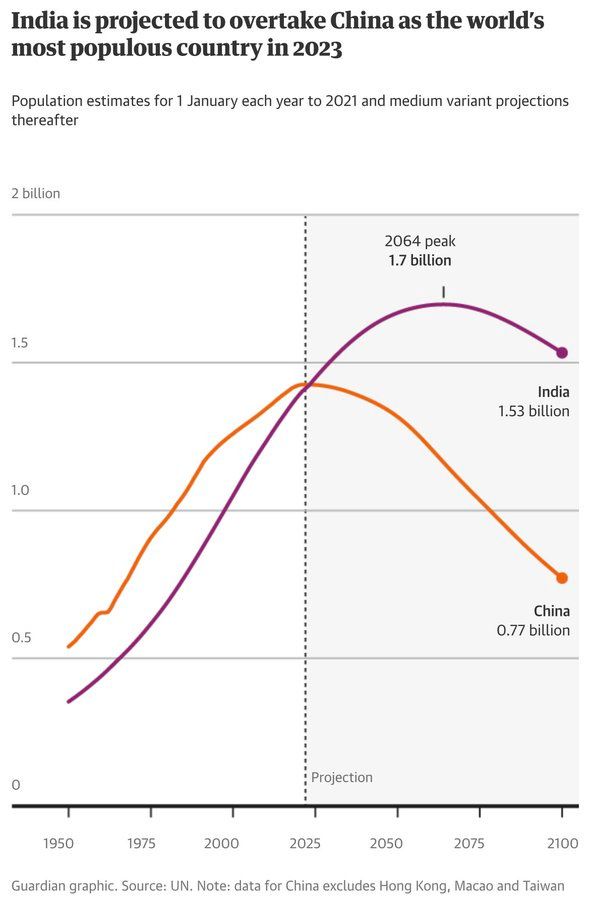

In 2023 India surpasses China as the most populated country

Disposing China after 200 years

The West has begun to shift away from China to embrace India (despite Modi’s shortcomings). This may be the most important for finance.

China has begun to age and shrink; India and Africa are young and growing rapidly

By 2100, India will be twice the size of China

By the end of the century, Africa will be home to 40% of the world’s population1

China has supplanted the US as the major trading partner

China will soon be the dominant source of global demand

But may be falling into the ‘middle income trap’

The developed world is aging, and aging is (for the most part) inflationary.

Japan will lose 1/3rd of its population by 2060

Most countries (except India and sub-Saharan Africa) will face additional inflationary pressures as their dependency ratios worsen.

Climate related migration is a wild-card; currently, the vast majority of cross-border migration IS NOT climate driven, however the 2nd order effects of climate change on migration patterns appears to be non-linear.

Recent Observations

The last demographic post went into considerable detail on the global changes underway, and the implications per Goodhart and Pradhan on global growth (via the change in the global dependency ratio). Here I will share a few recent observations.

Global

8 billion and counting (ABC)

While the Earth’s population is growing quickly, the growth rate is starting to slow down. Eventually, it will start falling and our societies will shrink.

We’ve already hit peak child – there will never again be more children alive than there are today, with fertility rates plummeting across the globe.

We’re getting older and older, which means there are fewer people able to work to support more people who can’t.

Cities are expanding, chewing up arable farmland as they go.

We’re seeing a major shake-up of the huge population centres of the world.

Under its most likely scenario, the UN projects the world population will reach about 10.4 billion in the 2080s.

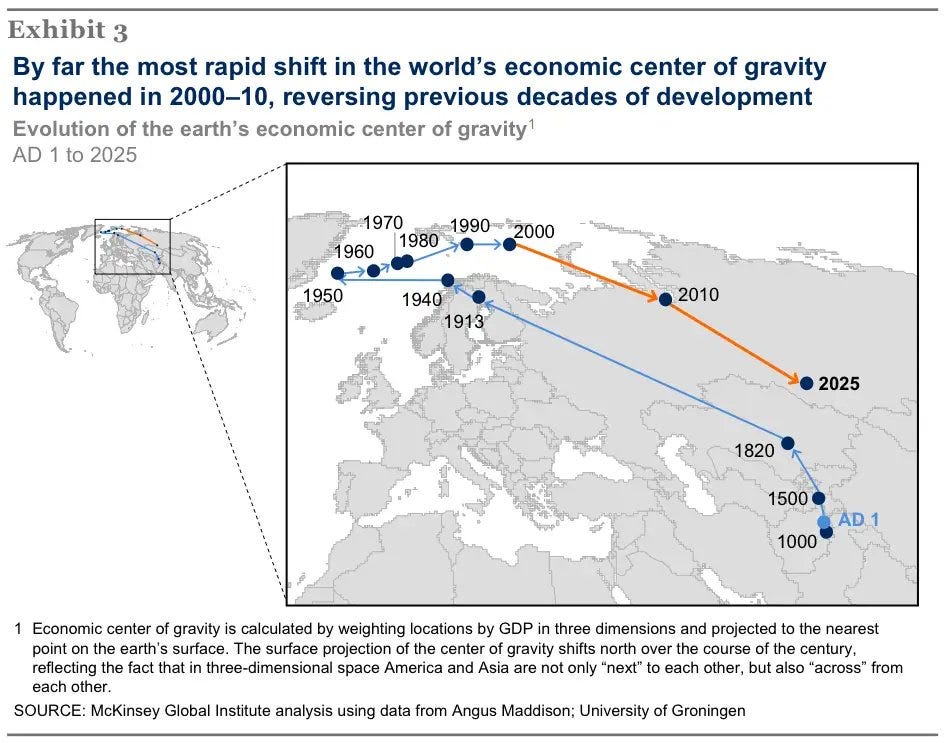

The Center of Economic Gravity Moved East

China Emerging As Dominant Source of Demand

[**** EXPAND THIS SECTION ***]

[In China], the number of households with disposable income above 35,000 US dollars will be twice as large as the total number of households in the US in 2030.2

Chinese Aging

China’s Biggest Threat Is Coming From Within (Bloomberg)

The country’s working-age population peaked a decade ago, and has since shrunk by 50 million people, Standard Chartered analysts highlight. The number of young workers (15 to 24) saw its all-time peak way back in 1987. The decline in the ranks of working-age people will accelerate from 2028, averaging 11 million a year to 2050, the bank says.

That’s a lot fewer income-earners to buy goods, and a lot fewer contributors to the public pension system.

The West (Finally) Pivots Towards India

Close India relations reflect bipartisan consensus in US politics (Chatham House)

Combined with its position as the world’s largest democracy, a leader in technology and science, and a youthful nation, India makes for a compelling and attractive partner. US–India connections are already strong: 4 million Indians reside in the US – a rapidly growing demographic and a wealthy one, with incomes double that of the median American household. The US is also India’s largest trade partner, with trade between the countries exceeding $191 billion in 2022.

Biden’s embrace of Modi is unambiguous. Modi’s US visit was timed to follow, and rather grandly, on the heels of US diplomacy in Asia, including high-level visits to South Korea, Japan, and finally Secretary Blinken’s trip to Beijing.

The strategic relationship also reaps material benefits. Modi’s visit concluded with announcements for deepening defence, technology, and space cooperation. India would also join the Mineral Security Partnership. An Indian Ocean Dialogue, designed to promote regional coordination across the region, was launched.

An agreement for General Electric to co-produce fighter jet engines designed by the US in India stood out – especially given India’s status as a partner, not an ally, of the US.

BP Comment: Finally, an aggressive shift towards India. I have bee espousing the need for this for a long time. With investment in China now facing frictions, opening India to capital flows solves a few problems. The US/West has excess savings and needs suitable investments; India needs capital deepening to support its rapid growth. India needs to fix its legal system and governance, but the history of Indian migration to the US sets up a stronger relationship than going into Africa at this time. Indonesia should be a major target as well.

US Trade With Africa Has Fallen, While Chinese Trade Has Expanded

Implications of Demographic Shifts

Demographics & Inflation

In 2018, the BIS published a study: The enduring link between demography and inflation.

[I]nflationary pressure rises when the share of dependants increases and, conversely, subsides when the share of working age population increases. This relationship accounts for the bulk of trend inflation, for instance, about 7 percentage points of US disinflation since the 1980s. It predicts rising inflation over the coming decades.

An economic interpretation of the age structure effect reveal a distinct pattern: the young age cohorts are inflationary, the working age cohorts are disinflationary, whereas the old are initially inflationary but turn highly disinflationary as they grow very old.

Our findings (as of 2018) suggest that the deflationary effect that the age structure has had on inflation for the past four decades will reverse over the coming decades and become inflationary.

Demographics & Growth

The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population

It is a distinct possibility that global population will decline rather than stabilize in the long run. In standard models, this has profound implications: rather than continued exponential growth, living standards stagnate for a population that vanishes. Moreover, even the optimal allocation can get trapped in this outcome if there are delays in implementing optimal policy

In many growth models based on the discovery of new ideas, the size of the population plays a crucial role. Other things equal, a larger population means more researchers which in turn leads to more new ideas and to higher living standards.

To sustain a constant population requires a total fertility rate slightly greater than two in order to compensate for mortality. The graph shows that high income countries as a whole, as well as the United States and China individually, have been substantially below two in recent years. According to the United Nations’ World Population Prospects 2019, the total fertility rate in the most recent data is 1.8 for the United States, 1.7 for China and for High Income Countries on average, 1.6 for Germany, 1.4 for Japan, and 1.3 for Italy and Spain. In other words, fertility rates in the rich countries of the world are already consistent with negative long-run population growth

When population growth is negative, both endogenous and semi-endogenous growth models produce what we call the Empty Planet result: knowledge and living standards stagnate for a population that gradually vanishes.

How Much Does Aging Really Hurt A Country?

Noah Smith covers aging in a Substack titled How much does aging really hurt a country?

The most obvious way that aging harms a country’s living standards is just by increasing the old-age dependency ratio — that is, the ratio of people over 64 to people aged 15-64. Retirees are retired, and hence they’re not adding much economic production to the country. So when a country gets older, it means that a shrinking percentage of workers has to support a growing percentage of retirees — that’s just simple arithmetic. Here’s a map of old-age dependency ratios around the world; you can see that Europe and Japan really stand out.

A higher dependency ratio means that productivity growth doesn’t translate into as big of an increase in living standards.

It’s actually pretty easy to study the effect of aging on the whole economy. … there’s a component of aging that’s basically baked into the demographic cake, and you can use that predictable component to study how aging affects the economy without worrying about reverse causation. In a 2022 paper, Maestas, Mullen, & Powell … find a strong negative effect of aging on growth for a number of economic variables:

Ozimek, DeAntonio, & Zandi (2018) look at specific industries within specific states, and … find that workers who have older coworkers tend to earn less — which, on average, probably means they’re less productive (though that relationship is far from exact). For skilled workers, the impact is even greater. …

In other words, even though studies generally find that older workers themselves are only very slightly less productive, there does seem to be some evidence that when a company is chock full of older workers, that company becomes less productive in general — possibly through the “ossified management” effect

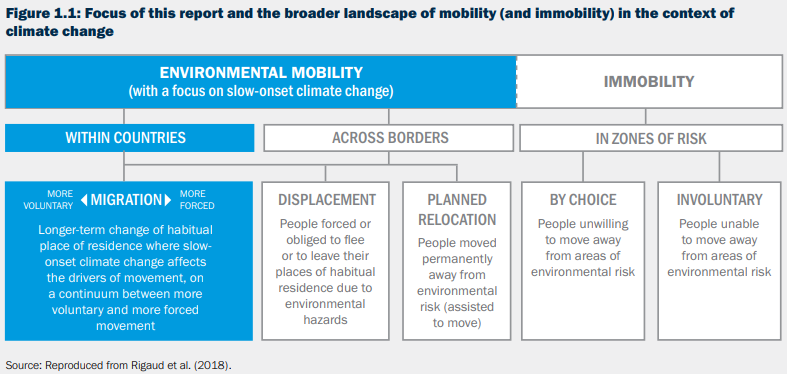

Climate Change Introduces a Wildcard

As the climate changes, it causes changes in peoples economic prospects. This seems to be a major cause of any migration (as opposed to the direct effect, such as the ocean taking away your land). The studies I have read suggest that migration is strongest over the shortest distance; first within country, then to nearby neighbors, and finally to significant distances (Africa to Europe; Venezuela to the US).

The risk here is that migration behavior may be non-linear and the option to migrate may be coming closer to the strike as temperatures increase.

Climate migration is forecast to be significant WITHIN countries

The initial model underlying the World Bank’s Groundswell Report3 forecasts that climate change may lead to nearly three percent of the population (totaling more than 143 million people) in three regions - Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America - to move within their country of origin by 2050.

[Part 2 of the Groundswell Report4 ] builds on the work of the first, modeling three additional regions, namely East Asia and the Pacific, North Africa, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia—to provide a global estimate of up to 216 million [within country] climate migrants by 2050 across all six regions.

Much of the published research focuses on migration WITHIN countries; there is a relative paucity of published research on the effect across countries.

A 2014 paper by Obokata, Veronis and McLeman, Empirical research on international environmental migration: a systematic review, provides an overview of the then existent literature. The papers they identify tended to look at specific countries and tended to focus on the specific effects of drought, not the broader set of climate issues. Many of the studies faced a paucity of useful data.

A significant question we asked was whether the empirical evidence bears out the starting assumption that environmental factors can influence international migration. Of the 31 empirical articles reviewed, 23 found some evidence of environmental factors influencing migration across international borders, while five others that looked for evidence did not find it.

They did state, however, that climate change was rarely the sole factor in “pushing” cross-border migration.

Finally, it cannot be overstated that the articles reviewed demonstrate that environmental influences rarely, if ever, act as a sole ‘‘push’’ factor of migration, meaning that political, economic, social, and demographic factors constantly interact with direct connections to whether, or how far, a person may migrate in times of environmental stress.

Summing up, our review suggests that, at least for the present, international migration for obvious environmental reasons is not occurring in vast numbers. There is evidence that second- and third-order impacts of environmental events and conditions also influence migration decisions, but there is insufficient evidence to offer an opinion as to how much larger the global number of international environmental migrants would be if these were taken into account. No definite conclusions can yet be drawn with respect to how international migration trends or patterns respond to specific environmental factors, or to specific socioeconomic drivers, individual circumstances, or combinations thereof; at this point, all that can be said with confidence is that there are many possibilities.

More recently, Šedová, Čizmaziová, and Cook published A meta-analysis of climate migration literature. They conclude:

Climate migration is most likely to emerge due to contemporaneous events, to originate in rural areas and to take place in middle-income countries, internally, to cities.

Their meta analysis finds:

While both extreme precipitation reduction and droughts unlikely reduce migration, their positive, yet insignificant effects on migration increase further support broader conclusions from the literature. Sea-level rise is likely to have an insignificant effect, contradicting conclusions … that sea-level rise is positively associated with migration. A possible explanation of our rather counter-intuitive findings is that the historical sea-level rise has not yet crossed the critical magnitudes that would trigger out-migration. Floods are likely to have an insignificant migration effect …We further find that hurricanes are unlikely to reduce migration…

We show that slow-onset climatic events (particularly temperature extremes and drying conditions) are generally more likely to increase migration than sudden-onset events(i.e. floods and hurricanes).

Our findings indicate an inverted U-shaped relationship between countries’ income levels and climate migration. We further show that migration responds to slow onset climatic events particularly in rural areas. Additionally, climate migration is likely to increase in response to contemporaneous rather than lagged adverse climatic events. As regards the destination choices, climate migration likely takes place in middle income countries, internally, and to destinations with lower dependence on the agricultural sector (i.e. cities).

Propublica and the NY Times have estimated that the failure to address climate-related migration will add apx. 680,000 legal migrants (and up to twice this amount of illegal migrants) to the US in the next 30 years above what would otherwise occur.

The NY Times Sunday Magazine had an article THE GREAT CLIMATE MIGRATION that had some original research.

We focused on changes in Central America and used climate and economic-development data to examine a range of scenarios. Our model projects that migration will rise every year regardless of climate, but that the amount of migration increases substantially as the climate changes. In the most extreme climate scenarios, more than 30 million migrants would head toward the U.S. border over the course of the next 30 years.

The model helps us see which migrants are driven primarily by climate, finding that they would make up as much as 5 percent of the total. If governments take modest action to reduce climate emissions, about 680,000 climate migrants might move from Central America and Mexico to the United States between now and 2050. If emissions continue unabated, leading to more extreme warming, that number jumps to more than a million people. (None of these figures include undocumented immigrants, whose numbers could be twice as high.)

Details about their model is here: Our Climate Migration Model

In Summary, The World in 2075

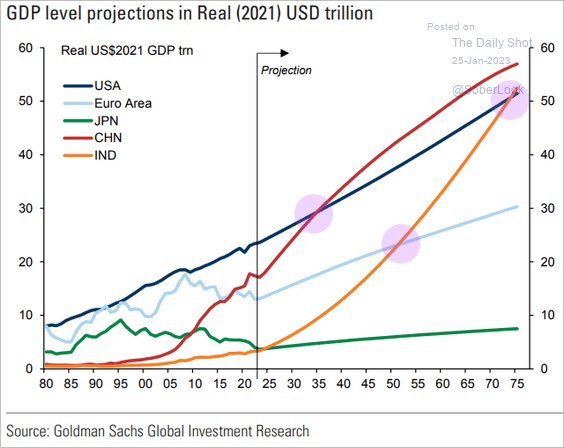

What Does World Economy Look Like Through 2075? Here’s What Goldman Sachs Thinks (Bloomberg)

Global growth will average just under 3% a year over the next decade, down from 3.6% in the decade before the financial crisis, and will be on a gradually declining path afterwards, reflecting a slowing of labor force growth.

Emerging markets will continue to converge with industrial nations as China, the US, India, Indonesia and Germany top the league table of largest economies when measured in dollars. Nigeria, Pakistan and Egypt could also be among the biggest.

The US is unlikely to repeat its relative strong performance of the last decade, and the dollar’s exceptional robustness also unwind over the next 10 years.

While income inequality between countries has fallen, it will continue to rise within them.

Our projections imply that we have passed the high-water mark of global potential growth,” the economists wrote in the note. “Most of this projected slowdown is due to demographics. Global population growth has halved over the past 50 years.

Glastonbury 2023

An awful lot of geezer rock (Elton John, GnR, Billy Idol, Crissie Hyndes; Blondie, etc) on the main stage. They looked like they needed wheelchairs.

Who knew that the highlight would be Rick Ashley doing a Smiths set, playing drums on Highway to Hell, and of course leading a sing-along?

Rick Astley with Blossoms - There Is A Light That Never Goes Out (Glastonbury 2023; youtube)

Rick Ashley - Highway to Hell (Glastonbury 2023; twitter)

Rick Astley - Never Gonna Give You Up (Glastonbury 2023; youtube)

Glastonbury is best watched on the BBC’s iPlayer where you can watch full sets.

I really enjoyed someone I never heard of before:

Rina Sawayama - XS (Glastonbury 2023; youtube)

Rina Sawayama - This Hell (Glastonbury 2023; youtube)

And I’m a huge Jacob Collier fan, so him leading a singalong is always a favorite of mine.

Jacob Collier - Somebody To Love (Glastonbury 2023; youtube)

And for fans of rave/electronica/dance:

Fatboy Slim - Praising You (Feat. Rita Ora) (Glastonbury 2023)

French, Megalopolis: how coastal west Africa will shape the coming century, The Guardian

BLS Capital: 2022 Annual Letter

Rigaud KK, De Sherbinin A, Jones B, Bergmann J, Clement V, Ober K et al (2018) “Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration,” The World Bank, Washington, D.C., (https://doi.org/10.7916/D8Z33FNS).

Clement, Viviane; Rigaud, Kanta Kumari; de Sherbinin, Alex; Jones, Bryan; Adamo, Susana; Schewe, Jacob; Sadiq, Nian; Shabahat, Elham. 2021. Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. © World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/36248 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Really great post Brian! A few thoughts come up as I read through it:

If so many societies will be struggling with aging populations and the inflationary consequences, could there be greater competition to attract younger working age talent to the affected economies? Seems to go against the trend of anti-immigration movements, and could also be counter to the likely growing trend of climate-related migration, though the latter could be a catalyst to encourage the pursuit of superior economic opportunities.

The other thought I had was whether the growing proximity of older populations to wildlife, which will likely continue to see its habitat shrink, could create 2020-like virus outbreaks and pandemics, which could rebalance the demographic picture. It is not clear that future pandemics would be more lethal to older populations, like in 1918 (I think). Climate change could also have a direct impact on this, with vector-borne diseases and heat-related deaths set to become more prevalent in higher latitudes.

I know this post is about the demographic factor, not technology, but it is impossible to think about productivity and inflation in the long term without considering the effect that the proliferation of AI will have on price dynamics. A shrinking working age population could still prove to be 5-10x more productive than your average worker in the age of ChatGPT and widespread plug-ins, as well as increased automation in manufacturing. A single worker armed with AI tools, could be as productive as an entire office, in theory. That could greatly offset tightness in the labor market and still generate enough growth to overcome the growing old age dependency ratio.