Perspective on Risk - Jan. 31, 2023 (Decoupling Update)

Globalization is (almost) dead; The End of the System of the World; Globalization is in Retreat; Pettis on China Decoupling; Not Reversing Any Time Soon; Decoupling is a Forecast; Cost of Reshoring;

Promised I had a big post coming. I’ve accumulated enough stuff to update the ‘decoupling’ theme. Lot’s of red meat for those that like this stuff. The next few will probably be more basic risk management.

Globalization is Dead and No One is Listening

Kevin Xu wrote an excellent recap of TSMC Chairman Morris Chang’s remarks on globalization at the ‘tool-in’ of their new Arizona semiconductor fab. If you read any of my links, read this one.

Taiwan’s TSMC is unarguably at the intersection of globalization and technology. While we have viewed deglobalization primarily through the great-powers lens, it is very informative to read a perspective by those affected. He argues, persuasively, that Chang provides a critical perspective as

TSMC is arguably the one company that most epitomizes all the forces of globalization – free trade, hyper specialization, cross-border supply chain, and the assumption of geopolitical stability that lets all these forces interact and interconnect.

Chang … reflected on the core nature of globalization and free trade, of which he and TSMC are beneficiaries.

In his speech, Chang declares:

“Globalization is almost dead. Free trade is almost dead. And a lot of people still wish they would come back, but I really don’t think they will be back for a while.”

Among the points Xu and Chang make are:

the chips produced from TSMC Arizona may cost “at least 50% more” than the chips from TSMC Taiwan. … The unfortunate second-order effect of the death of globalization that no one likes to talk about is the rising cost of all kinds of goods and products – a future that may make persistent inflation even worse.

TSMC cannot find enough qualified American talent to do the jobs TSMC needs to operate. So it must spend extra money (more cost) to send every new hire in America to Taiwan to get trained. Furthermore, due to this talent shortage, additional engineers from Taiwan must be hired, trained, and deployed to America to make TSMC Arizona function

there is also an equipment shortage and supplier shortage problem, so much so that TSMC has been shipping as many tools and equipment as possible, directly from Taiwan to Arizona.

The End of the System of the World

Noah Smith has authored The end of the system of the world. It is his ‘big-think’ attempt to understand and describe developments. It provides a nice long-term perspective.

The system of the world, 2001-2021

After the end of the Cold War, the United States forged a new world. The driving, animating idea behind this new world was the belief that global trade integration would restrain international conflict.

The U.S. and Europe championed the admission of China into the World Trade Organization, and deliberately looked the other way on a number of things that might have given us reason to restrict trade with China … As a result, the global economy underwent a titanic shift. Whereas global manufacturing, trading networks, and supply chains had once been dominated by the U.S., Japan, and Germany, China now came to occupy the central place in all of these:

The System Strains & Ruptures

In the mid-2010s, this compromise began to break down. On the U.S. side, there was increasing anger over the long-term decline of good manufacturing jobs, and an increasing feeling of the U.S. in second place. … An increasingly thin, fraying elite consensus in favor of the system snapped when Donald Trump came to power.

Meanwhile, in China, Xi Jinping initiated a program to onshore the production of high-value intermediate goods, even as rising labor costs started to force some low-value labor-intensive assembly work to places like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Xi also shifted China’s industrial policy from a regional patchwork to a unified national effort. Foreign direct investment as a percent of China’s economy dropped under Xi

In 2020 and 2021, a number of events convinced China’s leaders (and many observers in the U.S. and around the world) that China’s system had surpassed the U.S. in terms of economic vitality, political stability, and comprehensive national power. Most of these events were connected to the Covid pandemic.

Xi seemed to feel that China had extracted all it could from the Chimerica system, and that the benefits no longer outweighed the costs.

The key thing to understand about this decoupling, I think, and the reason it’s for real, is that this is something the leaders of both the U.S. and China want.

The new world system

One reasonable prediction is that the era of global value chains will not come to an end.

The second bloc is less certain. I expect the Biden administration and/or its successor to get tripped up for a while by the mirage of a self-sufficient U.S., and to implement “Buy American” policies that hurt our allies and trading partners and slow the formation of a bloc that can match China.

That bloc would not only include America’s formal allies or the developed democracies; instead it would include lots of developing countries that would like to hedge against Chinese power and secure access to rich-world markets. Two prime examples are India and Vietnam.

the economic relationship between China and developed democracies will stop being a symbiotic one and start to be a competitive one. Instead of being part of a value chain, Chinese and DD companies will go head to head in developing-country markets in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. Industrial policy in the DD countries will likely increase in order to maintain key technological edges that are relevant for military advantage.

the geostrategic competition between the DD countries and the China/Russia axis is obviously going to rely on a lot of export controls.

Finally, the disengagement from China is not going to be total or abrupt, no matter how much impetus there is in that direction.

a largely but not completely bifurcated global system of production and trade, with two technologically advanced high-output blocs competing head to head — seems like the most likely replacement for the Chimerica system that dominated the global economy over the past two decades.

Globalization is in Retreat

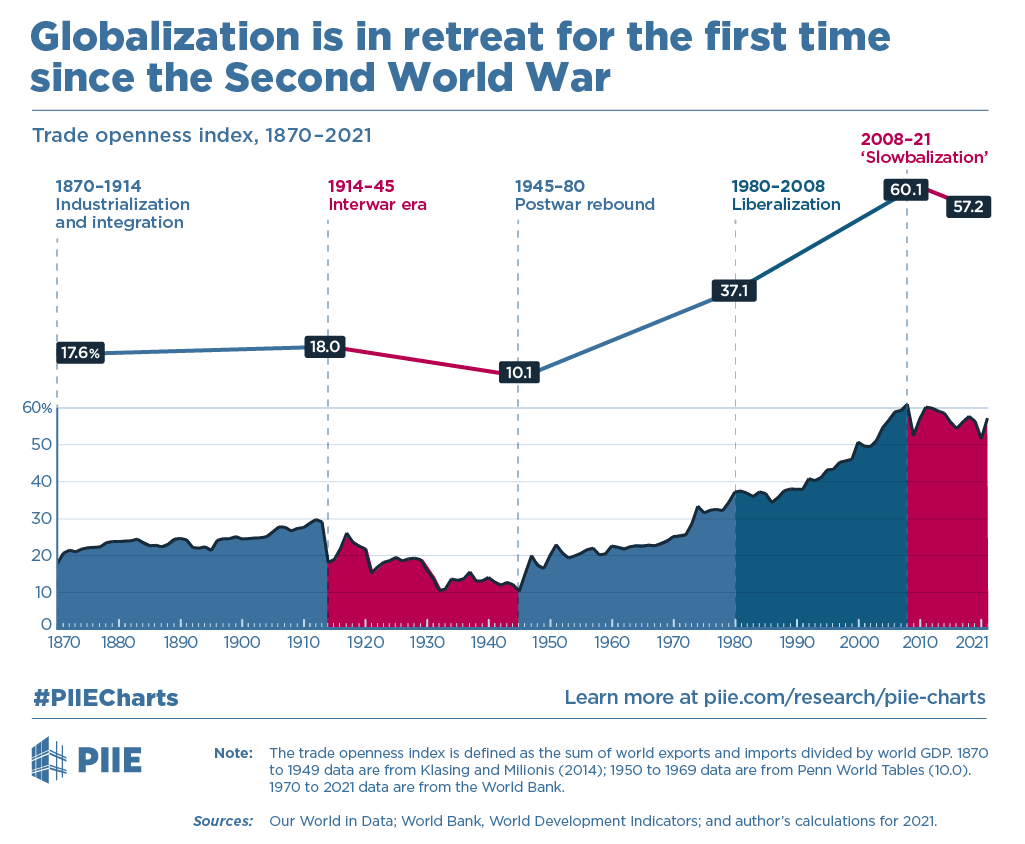

The Peterson Institute broke down history into five epochs in Globalization is in retreat for the first time since the Second World War, and argue that liberalization peaked in 2008.

Tracing global trade openness—the ratio of world imports and exports to world GDP—reveals five distinct eras of globalization since 1870.

Advancements in transportation deepened international economic integration prior to the outbreak of World War I.

The economic dislocation of war and protectionism during the Great Depression led to a reversal of globalization from 1914 to 1945.

Economic integration rebounded after the Second World War and continued to increase for the latter half of the 20th century.

An embrace of economic liberalization saw the removal of trade barriers in large emerging markets and led to unprecedented levels of international economic cooperation, peaking in 2008 at 60.1 percent.

Since this era of peak globalization, economic integration has been in retreat, falling to 57.2 percent on the openness index in 2021.

For those interested, the Peterson Institute is having a one-hour virtual presentation Globalization is dead—long live globalization! You can register at the link.

Pettis on China Decoupling

The China-specialist, economist, and iconoclast Michael Pettis weighs in on decoupling and supply chains, and flips the narrative on its head, and argues

The conventional explanation is that deglobalization is driven largely by politics, and that the economic problems associated with deglobalization are thus the consequences of this political process of deglobalization.

It could be that the adverse economic consequences are in fact the results of a global capital and trade regime that has been made obsolete by changes in global political arrangements and by innovations in transportation, communication and financial technology.

The alternate view argues that deglobalization is the reaction to a global capital and trade regime that has encouraged rising income inequality and surging debt, and has accommodated enormous – and enormously disruptive – trade and capital imbalances.

He further argues in this tweet stream

"decoupling from China isn’t going to be easy" for foreign manufacturers.

This is because

China-based manufacturers are so "competitive" internationally [because of] Chinese subsidies [that are] are far greater than those of any other country.

The extent of these subsidies explains China's huge domestic imbalances and the persistent weakness in its domestic demand. These subsidies must be paid for … by the household sector.

As long as China maintains these very high direct and indirect subsidies … moving manufacturing operations elsewhere will make them less competitive internationally.

So this raises a real issue of unintended consequences. The more we tariff Chinese goods, and encourage the movement of manufacturing out of China, the more we actually reduce the cost of China moving from its infrastructure-led policies to one based on greater domestic consumption.

Pettis notes:

Beijing has been promising to restructure the economy for well over a decade, in fact it is proving extremely difficult to do so, to the point that when Beijing worries about weak domestic demand, it typically responds by doubling down on manufacturing subsidies.

And the shift of China from a surplus to a deficit country is probably one of the bigger risks to dollar dominance (discussed later).

This Direction of Travel is Not Reversing Back to “Normal” Any Time Soon

Paul Singer is the Principal at Elliott Advisors. He’s usually an interesting read, and his letter last year was the basis of one of my first Perspectives. In a recent investor letter he laid out his views: Paul Singer’s Letter:

Globalization

Over decades, globalization lowered prices, increased efficiency, enhanced global growth and was widely considered a win-win for rich and poor countries alike. De-globalization is the reversal of those elements, driven by the physical supply chain issues unleashed by COVID-19 as well as the realization that countries which control important products, metals, minerals, and elements may not be reliably “friendly” toward the U.S. or other developed countries. Rather, they may actually be adversaries or enemies, and the low prices and reliable supply from such countries come with serious and possibly unaffordable costs, which may not only be measured in money. All of these factors go under the heading of sudden realizations. Obliviousness in these matters is yesterday’s newspaper. Realism is advancing. But make no mistake: De-globalization is inflationary and growth-suppressive. This direction of travel is not reversing back to “normal” any time soon, if ever.

Decoupling (of Supply Chains) is a Forecast

The American Prospect has an article, The Enduring Corporate Entrenchment in China, where they seek to debunk

claims that China has finally driven U.S. businesses away with rampant IP theft and obstacles to market access.

They state the following:

“There hasn’t been an across-the-board decoupling,” said Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Center on Foreign Relations and former senior adviser to the United States trade representative, over email. “The U.S. and the Chinese trade data don’t completely agree anymore (China reports more exports than the U.S. does imports) but the numbers suggest that China remains a very important source of supply for many manufactured goods. China’s share of global trade is actually up significantly compared to the year before the pandemic,” said Setser. …

A recent report by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai found that 19 percent of U.S. companies plan to reduce their investments in China, up from only 10 percent last year. According to that same study, another 30 percent plan to increase their investments.

Further:

On the other side, China can’t afford to cut ties with the global economy. The Chinese economy is reliant on exporting manufactured goods to acquire capital.

Concluding:

Current data and incentives therefore show that we can anticipate U.S.-China business as usual for some time.

Brad Setzer, in a Tweet stream notes:

China's overall data actually tells a story of the reglobalization of China's economy after the pandemic. Exports to GDP had been trending down from 2010 to 2018 -- but have moved up strongly in the past year.

And there is absolutely no sign that the G-7 already has decoupled from China as a source of supply! (imports from China have clearly boomed in the last 3ys)

In that light, Carl Quintanilla shared a UBS chart on intentions:

The Cost of Reshoring

Swiss Re has published A new world economic order in the making

The world is becoming more fragmented, with concerns about security exposing growing fissures.

We see a new world order taking shake, one of multi-polar blocs of economic and strategic influence.

we believe the global circumstances currently in play are bringing renewed recognition of and focus on the real economy. With respect to a multi-polar global economy and what it means for the insurance industry, we see three real economy tenets shaping the world that will be:

Global supply-chain restructuring: The COVID-19 pandemic led to interruptions to trade flows, also of input goods. Deglobalisation sentiment was already in play before the pandemic began, but we expect supply chains will now further shrink and realign around regional trading blocs as a means to insulate businesses against future global shocks. The war in Ukraine has only instilled more urgency for re- and friend-shoring of production activity.

̤ Transition to a green economy: The move from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy is one pillar of the drive to mitigate the effects of climate change, and also achieve net-zero emission goals. The war in Ukraine has led to national energy security concerns and high energy prices, reaffirming and adding urgency to the need for national economies to go green.

Volatile and higher food prices: Food prices have soared since last year, and the war in Ukraine has also led to food shortages in many parts of the world. We expect food prices will remain volatile and higher than pre-pandemic levels and that in a multi-polar world, food insecurity could become more commonplace.

Current high levels of inflation are driving interest rates higher, leading to a reallocation of investment to the real economy.

Governments are set to provide a more meaningful catalyst for economic growth through higher spending on national defence, public infrastructure and the transition to a green economy

A second change is potential reform of the global monetary and financial system. In a world economy made up of multi-polar blocs with different trade and technology standards, payment systems and reserve currencies, the US dollarʼs dominance as the world’s currency reserve may no longer be sustainable, nor economically efficient. To cater to the needs of the more fragmented global economy, a future monetary system may continue to evolve into a direction where central banks hold a wider range of reserve assets.

We expect that interest rates will remain higher over the longer term, as inflation moves structurally higher rather than lower, as in the last 40 years. The following factors will underpin this dynamic:

The green transition will likely push inflation structurally higher due to drivers such as “fossilflation”, “greenflation” and “fiscalflation”.8 This is one of the key reasons we forecast that US headline CPI inflation will be around 0.6 percentage points (ppt) higher (+0.7 ppt for the euro area) on average in the years 2024 to 2033 than the average of the previous economic cycle (2010‒2019). This will feed into the higher interest rate environment. We forecast average 10-year yields of 3.4% in the year 2024 to 2033, up from 2.4% in the last cycle.

Weaker global yield anchors: Euro area and Japanese yields are often said to be the global low yield anchors. This comes as European and Japanese investors allocate funds overseas (eg, to US Treasury bonds) in search of returns, resulting in compressed yields in other regions. The European Central Bank (ECB), however, has brought down the curtain on years of ultra-loose monetary policy and is instead launching an anti-fragmentation tool aimed at staving off the danger of a sovereign debt storm.9 And in Japan, while the central bank has reiterated that the top priority is support economic activity with aggressive monetary easing centred on yield curve control,10 it is coming under increasing pressure to change course. This as other major central banks continue to accelerate the pace of monetary tightening, the effects of which manifest in a sharply depreciating yen.

Potential for “reverse currency wars” as interest rates in major economies are hiked aggressively to fight inflation. Today, policymakers welcome stronger currencies to tame inflation, and also to maintain purchasing power over imports. The Fedʼs hawkishness has driven the US dollar significantly higher with the euro falling back to parity in mid-July this year, the first time this has happened since the global financial crisis. The spectre of currency depreciation is exerting further pressure on other economies to keep pace with the Fed as weaker currencies experience additional inflationary pressures. It has been estimated that central banks in major advanced economies will need to raise interest rates on average by an extra 0.1 ppt to offset a 1% decline in their currencies.11

Central bank balance sheet reduction: As central banks embark on quantitative tightening (QT) to reduce their balance sheets, the associated reversal of liquidity provisions should increase the cost of capital, pushing yields higher. This is especially true should QT be conducted through active sales of securities on central bank balance sheets, rather than letting the investment mature and subsequently decrease central bank reserves. In contrast to the last tightening cycle and QT episode, the Fed now has reverse repurchase operations through which it drains excess liquidity. As long as the US Treasury funds itself through bills and notes (the current baseline), the private sector does not need to absorb more duration. Hence mechanically higher yield levels are not a given.

Geopolitical developments could call into question the functioning of the global financial system……such as a new Bretton Woods, or a Bretton Woods 3.0. We identify three key principles for Bretton Woods 3.0:̤

reinforce the system of international governance and cooperation in an increasingly multi-polar world (including increasing the pace and scale of global reforms to enable a more environmentally sound, sustainable, and inclusive future);

expand the scale and scope of the Global Financial Safety Net (GFNS); and

build fiscal policy space at a global level to be allocated to individual nations according to need and circumstance

Role of the Dollar

Michael Pettis discounts the risk to dollar dominance; he suggests our superpower is:

[providing] the deficits needed to accommodate the surpluses of countries like China, Germany, and Japan, by running the capital account surpluses that accommodate their excess savings, the US share of global manufacturing must decline as the share of the surplus countries rises.

As long as these countries run surpluses, and as long as the US financial markets absorb their excess savings, the US must run deficits.

So the risk is that some other country (China) shifts from running surpluses to deficits. Probably not going to happen anytime soon, but who knows.

Hyun Song Shin, the Head of Research at the BIS, was prodded by the OddLots team to consider Zoltan Poszar’s thesis that the world will move away from the US dollar. He notes, as summarized by Weisenthal and Alloway:

The dollar’s strength is reinforced by an interlocking web of receipts and liabilities that are difficult to untangle.

and

any move away from a dollar-centric universe runs into practical and theoretical problems

The BIS further notes, in its Triennial Survey that the dollar remains dominant.

Confirmation Bias

Global central banks bought almost 400 tons of gold in the third quarter last year, the biggest quarterly addition on record, according to data published by the World Gold Council in January. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) was among the buyers, it said, while Russia was rumoured to have also loaded up.

The PBOC bought 30 tons of gold in December to diversify its foreign reserves, after adding 32 tons in November in its first purchases since September 2019. The two rounds of buying lifted its holding to 2,010 tons, valued at about US$120 billion at current market prices, or 3.6 per cent of its US$3.3 trillion reserves.

Just for reference, the United States holds the largest stockpile of gold reserves in the world, with over 8,100 tons.

Biden sends top officials to try to win over African nations long-wooed by China and Russia (CBS)

The United States' Ambassador to the United Nations is heading to Africa this week. She'll be the second member of the Biden cabinet to visit this month as the administration seeks to demonstrate its commitment to addressing the myriad challenges facing the continent, from conflict to climate change.

While neither Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield nor Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who arrived several days ago, have spoken directly about countering any other nation's influence, their visits are also a clear bid by Washington to answer both China and Russia's significant and expanding economic, political, and military influence across Africa.