Perspective on Risk - Dec 27, 2023 (Big Picture update)

TL;DR; The Big Three (demographics, globalization, technology);

Let’s close the year by revisiting the big picture thesis. The Big Picture discussion evolved out of reviewing Zoltan Poszar’s decoupling work back with this Sept. 1, 2022 Perspective. The thesis is that these three factors drive longer-term evolution. The interlocking circles were introduced in a discussion of demographics in the Sept. 16, 2022 Perspective. I’ve posted a list of Big Picture related Perspectives in the footnotes.1

Summary; TL;DR

If you don’t want to read the whole piece:

Demographics

Little has changed; unsurprising as this is the slowest moving of the three forces

US population is projected to be stable, reaching a high of nearly 370 million in 2080 before edging downward to 366 million in 2100.

By 2050, people age 65 and older will make up nearly 40 percent of the population in some parts of East Asia and Europe. That’s almost twice the share of older adults in Florida, America’s retirement capital. Extraordinary numbers of retirees will be dependent on a shrinking number of working-age people to support them.

Increasingly, it looks like “China will get old before it gets rich.”

Deglobalization/decoupling/dedollarization

Trade integration has been more rapid than ever (hyperglobalization); it is dematerialized, with the growing importance of services trade;

We are on the cusp of a proliferation of regional and preferential trade agreements and is on the cusp of mega-regionalism as the world's largest traders pursue such agreements with each other

Between the US & China, we’d expect to see a decoupling of foreign direct investment long before we saw a decoupling in actual trade. … That’s exactly what we’re seeing right now.

Foreign FDI into China has fallen off the cliff, and China may be reorienting its outflows away from Western economies towards ‘strategic relationships’ in Asia and Africa.

Technology

We’re seeing the emergence of a whole new computing paradigm (Generative AI), and it’s very very early.

The effects of Generative AI on productivity, income inequality, and industrial concentration is quite uncertain, and the path that results in low productivity growth, higher income inequality, and higher industrial concentration has the least resistance.

The real question is whether this is just normal technological progress or instead represents something more. I probably vote for ‘normal progress.’

China will use technology (capital deepening) to increase productivity as its working age population shrinks.

China is at the Intersection of All Three

They have the biggest demographic transition underway

Lacking a trusted convertible currency, they are vulnerable to dollar-based financing.

They need capital deepening to avoid the ‘middle income trap.’

Demographics

Demographic changes is perhaps the most predictable of the changes. We’ve reached the low point of the Chinese dependency ratio, and they have started to age quickly. India has grown and now surpassed the UK, France and Italy Perhaps the most interesting change is around the US. The US dependency ratio was projected to remain relatively stable, and the US population relatively younger than Europe and other areas, due to immigration.

I won’t spend much time here as this has been widely discussed previously. The NY Times has a nice summary piece: How a Vast Demographic Shift Will Reshape the World (NY Times)

By 2050, people age 65 and older will make up nearly 40 percent of the population in some parts of East Asia and Europe. That’s almost twice the share of older adults in Florida, America’s retirement capital. Extraordinary numbers of retirees will be dependent on a shrinking number of working-age people to support them.

This is a sea change for Europe, the United States, China and other top economies, which have had some of the most working-age people in the world, adjusted for their populations. Their large work forces have helped to drive their economic growth.

Not only are Asian countries aging much faster, but some are also becoming old before they become rich. While Japan, South Korea and Singapore have relatively high income levels, China reached its peak working-age population at 20 percent the income level that the United States had at the same point. Vietnam reached the same peak at 14 percent the same level.

Soon, the best-balanced work forces will mostly be in South and Southeast Asia, Africa and the Middle East, according to U.N. projections.

U.S. Population Projected to Begin Declining in Second Half of Century

The U.S. population is projected to reach a high of nearly 370 million in 2080 before edging downward to 366 million in 2100. By 2100, the total U.S. resident population is projected to increase by only 9.7% from 2022, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau population projections released today.

In each of the projection scenarios except for the zero-immigration scenario, immigration is projected to become the largest contributor to population growth.

(De)Globalization

Deglobalization —> Decoupling —> Dedollarization

The discussion of deglobalization has morphed to a more specific discussion of decoupling from China. Globalization is not dead, but is changing (dematerializing; regionalizing; increasingly north-south), and the US government has taken a much greater interest in making sure nationally critical strategic industries are in friendly hands (if not completely on-shored).

Deglobalization with Chinese Characteristics

Perhaps the most interesting new paper on globalization comes from Subramanian and Kessler, writing for the Peterson Institute: The Hyperglobalization of Trade and Its Future. If you’re a globalization nerd like me, this is your holiday reading.

This paper describes seven salient features of trade integration in the 21st century:

Trade integration has been more rapid than ever (hyperglobalization);

it is dematerialized, with the growing importance of services trade;

it is democratic, because openness has been embraced widely;

it is crisscrossing because similar goods and investment flows now go from South to North as well as the reverse;

it has witnessed the emergence of a mega-trader (China), the first since Imperial Britain;

it has involved the proliferation of regional and preferential trade agreements and is on the cusp of mega-regionalism as the world's largest traders pursue such agreements with each other; and

it is impeded by the continued existence of high barriers to trade in services.

Going forward, the trading system will have to tackle three fundamental challenges:

In developed countries, the domestic support for globalization needs to be sustained in the face of economic weakness and the reduced ability to maintain social insurance mechanisms.

Second, China has become the world’s largest trader and a major beneficiary of the current rules of the game. It will be called upon to shoulder more of the responsibilities of maintaining an open system.

The third challenge will be to prevent the rise of mega-regionalism from leading to discrimination and becoming a source of trade conflicts. We suggest a way forward—including new areas of cooperation such as taxes—to maintain the open multilateral trading system and ensure that it benefits all countries.

Another paper from the IMF, Long Live Globalization: Geopolitical Shocks and International Trade, comes to similar conclusions:

Are we really witnessing the death of globalization? … Using an extensive dataset with more than 4 million observations, I develop an augmented gravity model … and find that the much-debated geopolitical alignment between countries has contradictory and statistically insignificant effects on trade, depending on the level of economic development.

Ed Price comments on this later paper in the Global trade ≠ globalisation (FT Alphaville):

Economic policy is saying one thing. Economic data, another. Trade is robust, and more robust than antitrade policies.

Perhaps the real issue is how bad geopolitical risk will be. The IMF paper suggests that, right now, it ain’t so bad. Geopolitical risk was certainly a lot higher in the 1940s than it is today.

Decoupling

In Stop saying "there is no decoupling". There is! Noah Smith takes the aforementioned Subramanian paper and adds thoughts and observations from the usually excellent work of The Rhodium Group. He writes:

the decoupling narrative has focused on the fact that the U.S. is getting fewer of its imports from China in recent years:

We’d expect to see a decoupling of foreign direct investment long before we saw a decoupling in actual trade. … That’s exactly what we’re seeing right now. Money flowing into China appears to be falling, but so much money is exiting China that net FDI into the country has almost completely collapse

Balding notes that because profits from FDI already in China that cannot be repatriated is counted as new FDI, this probably means there was effectively zero or even negative new FDI into China.

Further, as Brad Setzer and others have noted, much of the decoupling has already occurred, as China has effectively decoupled by onshoring (to China) component production as they have moved up the economic food chain:

a lot of the deglobalization that we’ve seen since 2008 was just China decoupling from countries like Japan and Korea and Taiwan that it used to depend on for high-value components.

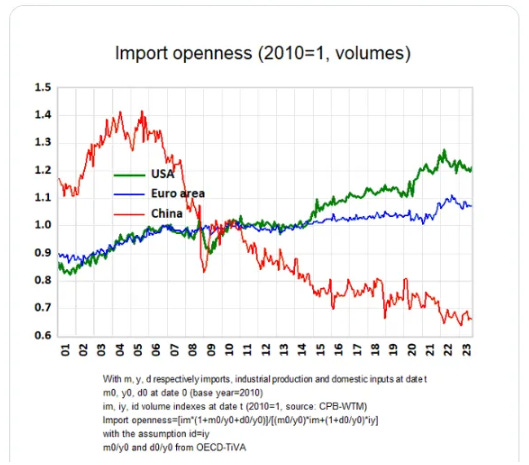

Brad Setzer shares this graph from French economist Guillaume Gaulier that shows the Chinese deglobalization from 2008 onwards:

Noah shares four observations from The Rhodium Group":

Firms—foreign and Chinese—are actively diversifying investment and sourcing away from China, in sensitive as well as less sensitive sectors.

Because global value chains are so entangled with China, diversification will not necessarily result in a reduced reliance on Chinese inputs and suppliers in the short- to medium-term.2

Because China’s manufacturing clout is so significant, even substantial shifts in production to alternative destinations may only result in small declines in China’s share of global exports

These realities mean that it will take years for advanced economies to achieve the objectives behind their “de-risking” policies—namely limiting trade, investment and supply chain exposure to China in a subset of critical areas.

Brad Setzer summarizes the state of play succinctly:

Bilateral trade between the US and China is down (even in the Chinese data). Measurable financial flows between the US and China have disappeared. But China's good surplus could not exist without a deficit of comparable size elsewhere, and that deficit is in the US

Lastly, the WSJ has an interesting, if mostly anecdotal observations is Chinese Money Flees the Western World:

Chinese investment is retreating from the West as hostility to Chinese capital has grown. Increasingly, Chinese companies are instead spending money on factories in Southeast Asia and mining and energy projects in Asia, the Middle East and South America, as Beijing seeks to cement alliances in those places and secure access to critical resources.

Direct overseas investment from China to the rest of the world fell by 18% from a year earlier by one new measure released recently. The latest level marks a decline of 25% from a peak in 2016, as overseas mergers and acquisitions have plummeted and Beijing has tightened rules to curb capital flight.

Dedollarization

As a reminder, we use Hyun Shin’s four step process for evaluating a global reserve currency: 1. Invoicing transactions, 2. Trade Financing, 3. Investing and borrowing and 4. Currency hedging. Using these criteria I had concluded the risk to the dollar, while real, was still a ways off.

“De-dollarisation is happening, but very, very gradually,” says UC Berkeley's prof. Barry Eichengreen

In August, the five Brics countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — invited six more countries, Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, to join their emerging market club. In early September, Indonesia set up a national 'de-dollarisation' task force.

We have seen scattered reports of trade non-dollar invoicing, but nothing meaningful. The Asian Development Bank reports that more than 80% of exports in Asia are still invoiced in dollars.

Data from 2022 indicated that the dollar was on one side of the trade for over 97 percent, 95 percent, 94 percent, and 88 percent of Indian rupee, Brazilian real, Chinese renminbi, and South African rand foreign exchange transactions, respectively. Data also indicated that in 2022, globally, the dollar was on one side of the trade for almost 90 percent of all foreign exchange transactions.3

Overall, exchanging BRICS’ currencies with other emerging market currencies can often be costlier relative to the dollar and can involve settlement risk due to the lack of financial infrastructure that mitigates such risk. As for recent BRICS invitees, their economies are heavily sanctioned, are on the verge of currency crises, or have dollar-pegged currencies.

… the amount of renminbi available outside of China remains quite limited relative to the dollar, and the currency’s cross-border usage in payments is greatly eclipsed by the dollar’s role

China has shifted the majority of its foreign lending from the dollar to the yuan. The thought appears to be that countries that borrow in the yuan are more likely to use the currency for international payments. Forty countries now have swap lines with China.

Technology

Generative AI Will Change Everything

A year ago, large language models (LLMs) did not exist for public use. Now they are being integrated into all sorts of products. This so-called Generative AI has at least theoretically already impacted skilled employment.

One early study, based on the relatively release of the relatively privative ChatGPT model, The Short-Term Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Employment: Evidence from an Online Labor Market, has found

… that freelancers in highly affected occupations suffer from the introduction of generative AI, experiencing reductions in both employment and earnings. We find similar effects studying the release of other image-based, generative AI models.

… These results suggest that in the short term generative AI reduces overall demand for knowledge workers of all types, and may have the potential to narrow gaps among workers.

OpenAI and Google have already rolled out significantly more powerful models, GPT4 and Gemini.

Looking at LLMs as chatbots is the same as looking at early computers as calculators. We’re seeing the emergence of a whole new computing paradigm, and it’s very early. (Andrej Karpathy)

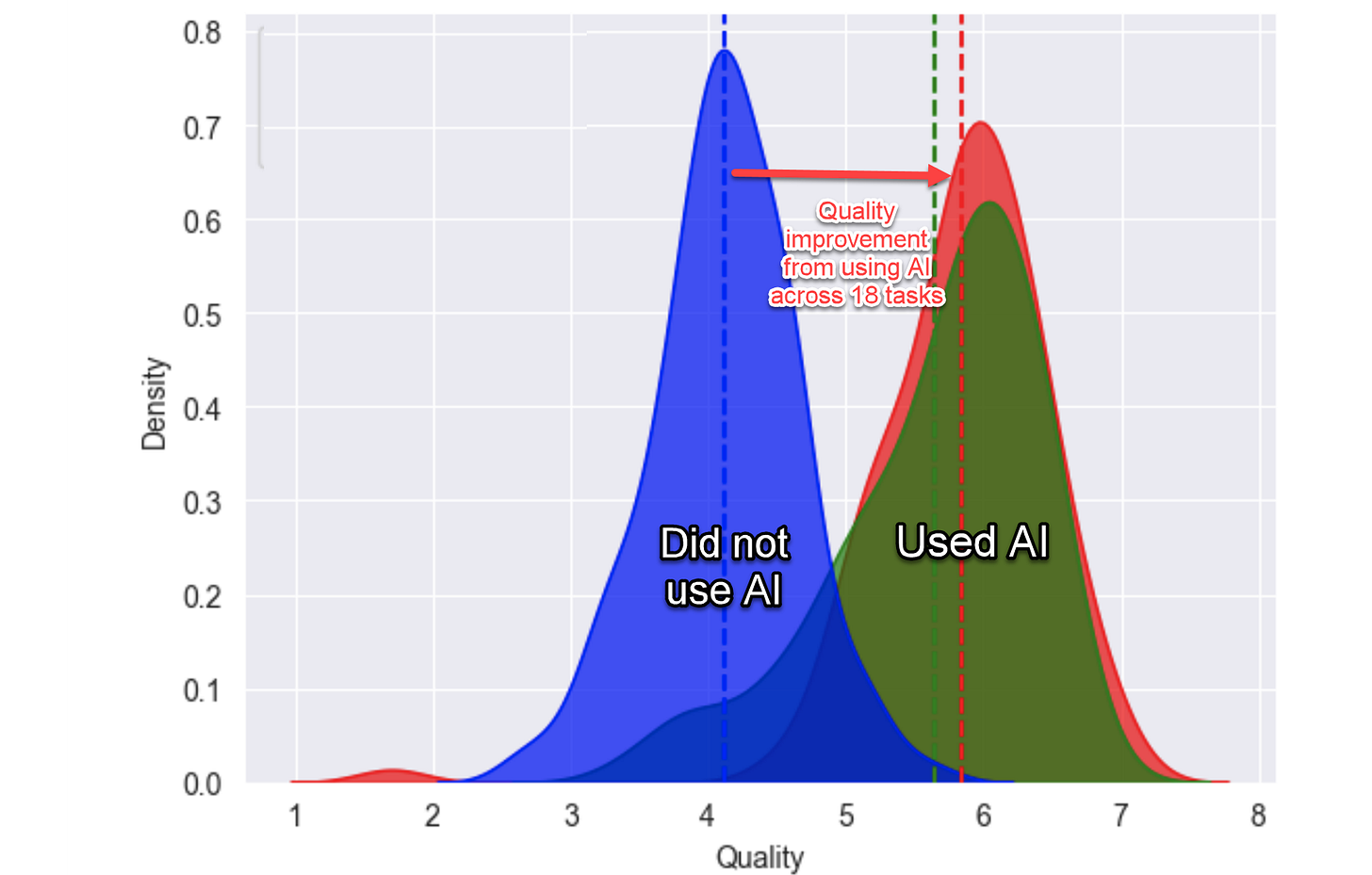

Another study, Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality, conducted with Boston Consulting Group found significant increases in consultant productivity. Importantly, it appears to erode the premium for higher skills.

For each one of a set of 18 realistic consulting tasks within the frontier of AI capabilities, consultants using AI were significantly more productive (they completed 12.2% more tasks on average, and completed task 25.1% more quickly), and produced significantly higher quality results (more than 40% higher quality compared to a control group).

Consultants across the skills distribution benefited significantly from having AI augmentation, with those below the average performance threshold increasing by 43% and those above increasing by 17% compared to their own scores. For a task selected to be outside the frontier, however, consultants using AI were 19 percentage points less likely to produce correct solutions compared to those without AI.

Ethan Mollick, who worked on the study, commented on it in his substack post: Centaurs and Cyborgs on the Jagged Frontier with this conclusion:

… let me tell you the headline first: for 18 different tasks selected to be realistic samples of the kinds of work done at an elite consulting company, consultants using ChatGPT-4 outperformed those who did not, by a lot. On every dimension. Every way we measured performance.

The rise of Generative AI will affect all sorts of macro-economic variables. The IMF has taken a first stab at outlining some of the potential futures in The Macroeconomics of Artificial Intelligence. The areas they discuss are productivity, income inequality, and industrial concentration. The conclude:

For each of the forks in the road, the path that leads to a worse future is the one of least resistance and results in low productivity growth, higher income inequality, and higher industrial concentration. Getting to the good path of the fork will require hard work—smart policy interventions that help shape the future of technology and the economy.

Also: ‘Robots can help issue a fatwa’: Iran’s clerics look to harness AI (FT)

“Robots can’t replace senior clerics, but they can be a trusted assistant that can help them issue a fatwa in five hours instead of 50 days,” said Mohammad Ghotbi

Demographics

Perspective on Risk - Sept. 16, 2022 (Demographics)

Perspective on Risk - June 28, 2023 (Demographics)

Technological Change

Perspective on Risk - Dec. 9, 2022 (Technology)

Perspective on Risk = Jan. 17, 2023 (Technology & Productivity)

Perspective on Risk Jan. 25, 2023 - Technology Implications

Globalization/Decoupling

Baldwin, Freeman & Theodorakopoulos show the extent of ‘hidden’ Chinese exposure in supply chains in Hidden Exposure: Measuring US Supply Chain Reliance