Perspective on Risk - July 28, 2023 (Climate)

Ole, Ole, Ole, Ole; Dramatic Change in Policy Is Needed; Climate Risk Exposure Measurement; Climate Change, Financial Stability & Regulation; Deep Dive on Decarbonization

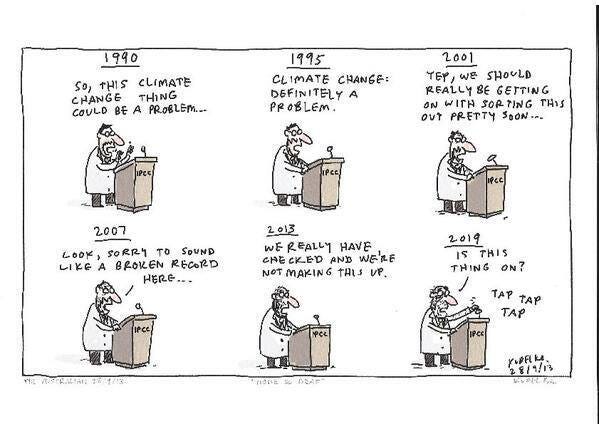

I haven’t been bothering you with this (unless you are David or Alessa) for quite some time. Thought it a good time to provide you with some thoughts and primary source material. Past Perspectives on climate risk are here if you are interested.

Perspective on Risk - Nov. 9, 2022 (Climate Again)

Ole, Ole, Ole, Ole … Feeling Hot, Hot, Hot

Feeling Hot Hot Hot - The Merrymen (Youtube)

I will presume for the purpose of this post that everyone is very aware of the record global heatwave that is underway, and will not repeat what is easily read in the routine media.

At a first level of understanding, we are seeing heat records being broken around the world, and that the records are not just being broken by a little, but rather are being shattered. This is causing severe storms, droughts and fires, coral bleaching and other effects as weather patterns change.

At the second level, you may understand that a big concern is the unprecedented heating of the worlds oceans. Depending on the measure, this years heating represents a 4-6 std. dev. event. As you can see from the chart below, the North Atlantic has already set a new all-time high, at least one month ahead of the peak period of heating.

The oceans can hold a tremendous amount of energy, but this then gets released as additional water vapor for the atmosphere.

Is The AMOC Reaching A Tipping Point

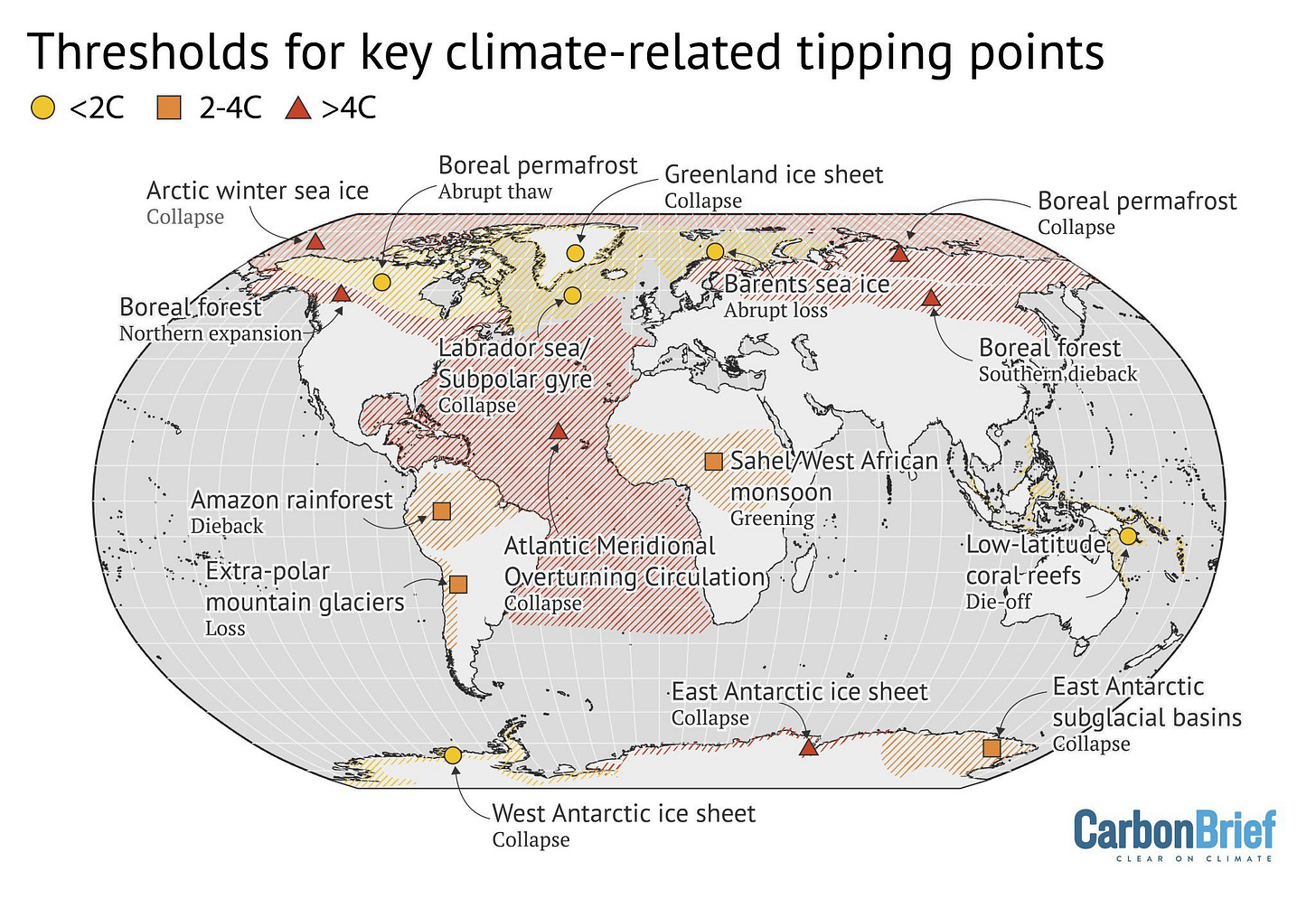

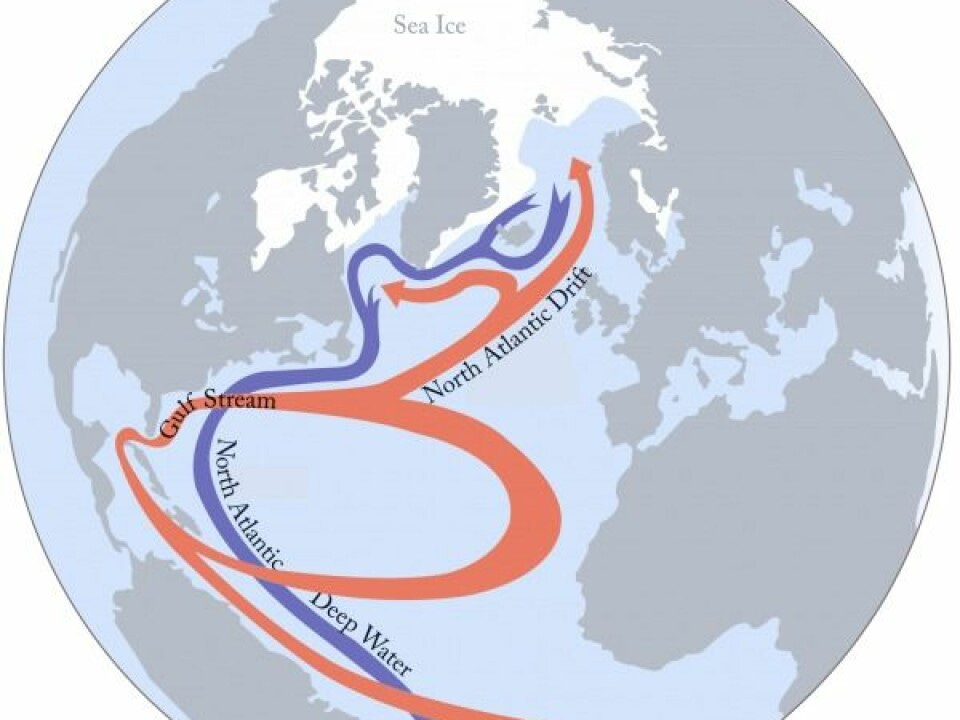

In the last few days, you may have read about the Atlantic Meridian Overturning Circulation, or AMOC for short. The possible collapse of the AMOC is one of a number of critical climate change tipping points identified by scientists. The Gulf Stream, with which we are more familiar, is one part of the AMOC. The circulation is sensitive to the addition of fresh water from the Greenland ice sheets as this makes the cold water less dense.

A paper was published in Nature Warning of a forthcoming collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Using a variety of historical data and state of the art climate models, the authors model the possibility of the AMOC reaching a ‘tipping point.’ The paper is long on scientific jargon and notation. Anyway, they conclude:

We predict with high confidence the tipping to happen as soon as mid-century (2025–2095 is a 95% confidence range).

Here is a very short (<10 min) video of Prof. Stefan Rahmsdorf on Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation at the Exeter conference on Climate Tipping Points. I highly recommend watching this short video. If you want to be the most knowledgeable person at the next cocktail party, and don’t want to read the paper, watch this clip (you can skip the first 30 seconds).

https://twitter.com/i/status/1684149268855107586

A slowdown of the AMOC leads to a cooling area south of Greenland, and a warming of the Atlantic Coast.

Estimate that there has been a 15% weakening of the AMOC since 1950. This may be the weakest the AMOC has been since the end of the Holocene era (4000-8000 years ago).

A collapse of the AMOC is predicted to lead to a significant drop in temperatures in Northern Europe and eastern North America, a substantial rise in sea level along the U.S. East Coast, adverse effects on fisheries and the jet stream, which in turn impacts weather patterns across the globe.

When Will We Breach the 1.5C and 2.0C Targets?

And Is Temperature Chane Non-Linear?

A working paper from Hansen et. al. Global warming in the pipeline states:

Global warming in the pipeline is greater than prior estimates. Eventual global warming due to today's GHG forcing alone -- after slow feedbacks operate -- is about 10°C.

Under the current geopolitical approach to GHG emissions, global warming will likely pierce the 1.5°C ceiling in the 2020s and 2°C before 2050.

Interestingly, part of the warming is the result of our successful efforts to eliminate aerosol emissions in order to protect the ozone layer.

Also, of even more interest, is that it looks as if the change in temperature is non-linear. You all know how I love my non-linearities.

Hansen has another interesting piece where he shows the changing probability density functions for North American temperature anomolies.

NASA Suggests Sea Level Rise Is Accelerating

NASA Study: Rising Sea Level Could Exceed Estimates for U.S. Coasts

New results show average sea level rise approaching the 1-foot mark for most coastlines of the contiguous U.S. by 2050. The Gulf Coast and Southeast will see the most change.

Global sea level has been rising for decades in response to a warming climate, and multiple lines of evidence indicate the rise is accelerating.

By 2050, sea level along contiguous U.S. coastlines could rise as much as 12 inches (30 centimeters) above today’s waterline, according to researchers who analyzed nearly three decades of satellite observations.

“A key takeaway is that sea level rise along the U.S. coast has continued to accelerate over the past three decades,” said JPL’s Ben Hamlington, leader of the NASA Sea Level Change Team and a co-author of both the new study and the earlier report.

Dramatic Change in Policy Is Needed

Oil

Coal

Global coal demand reached a new all-time high in 2022, rising above 8.3 billion tonnes (bt). It rose despite a weaker global economy, mainly driven by being more readily available and relatively cheaper than gas in many parts of the world. The turn to coal-fired generation was further supported by overall weak nuclear power and hydropower production, contributing to a new record global high of 10 440 TWh being generated from coal, representing 36% of the world’s electricity generation, up one percentage point compared to 2021.

Climate Risk Exposure Measurement

U.S. Banks’ Exposures to Climate Transition Risks

Jung et. al. has written U.S. Banks’ Exposures to Climate Transition Risks and a related Liberty Street blog post How Exposed Are U.S. Banks’ Loan Portfolios to Climate Transition Risks? (Liberty Street)

We exploit estimates from general equilibrium models of the decrease in output or profits of given industries as a result of certain climate transition policies.

The results show that while banks’ exposures are meaningful, they are manageable.

When we assume that loans to the top decile of industries go bankrupt, banks’ exposures increase by about 4 percentage points based on the estimates from Jorgenson et al. (2018). When we assume that loans to the top two decile industries go bankrupt, banks’ exposures increase by another 6 percentage points. Over time, the exposures to the most policy-sensitive industries appear to be declining.

As shown in the two charts below, banks appear to have increased their exposures to industries with relatively low climate transition risk exposures and to have reduced their exposures to industries with high climate transition risk exposures. Together, these charts suggest that banks on their own may be adjusting their lending portfolios both by lending more to “greener” industries and by lending less to “browner” industries.

CRISK: Measuring the Climate Risk Exposure of the Financial System

Jung, Engle and Berner, writing at my former employer, the NY Fed, have published a paper CRISK: Measuring the Climate Risk Exposure of the Financial System and a subsequent Liberty Street blog post on a market-based methodology for assessing banks’ “resilience to climate-related risks.” This is essentially an attempt to use the SRisk methodology to estimate climate exposure risk.

We develop a market-based methodology to assess banks’ resilience to climate-related risks and study the climate-related risk exposure of large global banks. We introduce a new measure, CRISK, which is the expected capital shortfall of a bank in a climate stress scenario. To estimate CRISK, we construct climate risk factors and dynamically measure banks’ stock return sensitivity (that is, climate beta) to the climate risk factor. We validate the climate risk factor empirically and the climate beta estimates by using granular data on large U.S. banks’ loan portfolios. The measure is useful in quantifying banks’ climate-related risk exposure through the market risk and the credit risk channels.

For methodology, the authors estimate exposures and then form “hedge portfolios”

The market based methodology to measure the transition risk exposure of financial institutions involves three steps. The first step is to build stress test scenarios by constructing portfolios designed to respond to climate risk. The second step is to estimate the time varying climate betas of financial institutions using the Dynamic Conditional Beta(DCB) model of Engle(2016). The third step is to compute CRISK, which is the expected capital shortfall conditional on climate stress.

We consider four climate risk factors: a stranded asset factor, an emission factor, a brown minus green factor, and a climate efficient factor mimicking portfolio factor.

Some of their conclusions:

Based on a sufficiently severe yet plausible scenario in which stranded assets sharply fall in value over a short horizon, we document a substantial rise in climate betas and CRISKs across banks during 2020.

In 2020, the aggregate CRISK of the top four US banks increased by 425 billion US dollars (USD), which corresponds to approximately 47% relative to their market capitalization. Our decomposition analysis reveals that 40% of the CRISK increase in 2020 was due to an increase in climate betas, and 40% was due to a decrease in equity values.

The real question is whether this is a risk that we should require banks to capitalize, and if so how. There is an argument that raising the capital costs of firms and projects that contribute to global warming would provide a useful incentive, but other mechanisms like a global carbon tax would be more efficient.

The analysis to look at the correlation of bank equity prices to ‘brown’ indices is interesting, but I think most would not find it determinative. Finally, the big problem here is that, at a firm level, risk is perceived to be short-term. Based on liquid markets, banks can shed exposures at relatively short horizons. The broader economy, however, cannot just ‘wish away’ the exposures. As a bank, I can get out of lending to flood prone markets, but as an economy the transition costs are enormous.

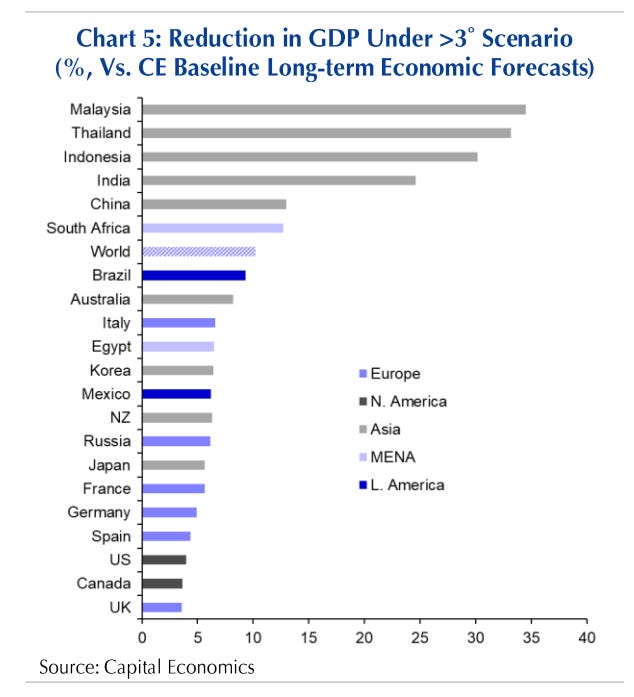

In The 3°C Scenario: What's the economic impact of severe global warming? James Pethokoukis discusses a paywalled paper by Capital Economics Quantifying the economic hit from climate change and reportedly quotes this critical finding:

But the key takeaway is that we think global GDP would still nearly double in size between now and mid-century even if the world were to warm by more than we anticipate, largely because developed economies would be affected the least. And even in places where a warmer world would have much bigger impacts on GDP, such as in India and south-east Asia, the physical effects on economic activity would be a headwind to catch-up growth rather than putting economic development in reverse.

What’s perhaps notable is that the 3C degree scenario hits two of the most rapidly growing economies the hardest (India and Indonesia). Still, they conclude that climate change would only provide a “headwind to growth rather than putting economic development in reverse.”

Climate Change, Financial Stability & Regulation

Fed Remarks on Financial Stability

Fed Gov. Waller gave a speech in May Climate Change and Financial Stability that discusses the Fed’s approach to climate change. This represents a downgrade to the importance of climate change on the Fed’s agenda and a welcome return to the mandate.

I believe that placing an outsized focus on climate-related risks is not needed, and the Federal Reserve should focus on more near-term and material risks in keeping with our mandate.

The following quotes are reformatted by me for easier reading:

My job is to make sure that the financial system is resilient to a range of risks. And I believe risks posed by climate change are not sufficiently unique or material to merit special treatment relative to others. … I want to be careful not to conflate my views on climate change itself with my views on how we should deal with financial risks associated with climate change.

Risks to financial stability have a couple of features. First, the risks must have relatively near-term effects, such that the risk manifesting could result in outstanding contracts being breached. Second, the risks must be material enough to create losses large enough to affect the real economy.

Broadly speaking, physical risks could affect the financial system through two related channels.

First, physical risks can have a direct impact on property values. …

Second, and a more compelling concern, is the notion that property value declines could occur more-or-less instantaneously and on a large scale when, say, property insurers leave a region en masse.

What about transition risks? Transition risks are generally neither near-term nor likely to be material given their slow-moving nature and the ability of economic agents to price transition costs into contracts. There seems to be a consensus that orderly transitions will not pose a risk to financial stability.

I don't see a need for special treatment for climate-related risks in our financial stability monitoring and policies. … Based on what I've seen so far, I believe that placing an outsized focus on climate-related risks is not needed, and the Federal Reserve should focus on more near-term and material risks in keeping with our mandate.

Climate-related Insurance Regulation

FIO issued Insurance Supervision and Regulation of Climate-Related Risks

FIO’s key findings and recommendations of this Report include:

Climate-related risks—including physical, transition, and litigation risks—present new and increasingly significant challenges for the insurance industry. The oversight of climate-related risks is therefore an emerging and increasingly critical topic for state insurance regulators. Climate-related risks also warrant careful monitoring by financial regulators, policymakers, and insurers.

State insurance regulators and the NAIC are increasingly focused on incorporating climate-related risks into supervision and regulation, but in most cases their efforts remain at a preliminary stage.

Current regulatory frameworks provide state insurance regulators with tools they can adapt to better consider climate-related risks. The NAIC and some state insurance regulators are beginning to incorporate climate-related considerations into their regulatory tools.

All state insurance regulators should prioritize efforts to adapt their regulatory and supervisory tools to incorporate climate-related risks. The NAIC and state insurance regulators should also prioritize the creation of new and effective climate-related risk tools and processes for use by state insurance regulators through, for example, the development of scenario analysis and increased use of the NAIC’s Catastrophe (CAT) Modeling Center of Excellence.

More work is needed by state and federal regulators and policymakers, as well as by the private sector and the climate science and research communities, to better understand the nature of climate-related risks for the insurance industry, their implications for insurance regulation and supervision, and for the stability of the financial system—including for real estate markets and the banking sector.

FIO makes 20 recommendations in this Report.

Brookings held a conference to discuss the findings: Assessing insurance regulation and supervision of climate-related financial risk (Brookings video; 1 hour) ….. Here is the transcript if you prefer. There is a panel discussion at the 24:40 mark that some of you may want to check out.

Somehow, taking a state-level approach to a global externality problem seems particularly wrong, but what do I know.

Deep Dive

140 slides from Nat Bullard on Decarbonization: The long view, trends and transience, net zero