I have a lot of things in the hopper; hard to decide what to write about. Been hoping to get out thoughts on Central Bank Digital Currency, Fintech, lots of market developments, but not ready yet.

Some thoughts on ESG (and climate change in particular).

I started to write this piece before Peter Zaffino, on the AIG earnings call, reiterated the following:

When analyzing the portfolio over the last five years, we've seen catastrophe levels that are 10 times the level the portfolio dealt with in the prior 10 years for losses in excess of $50 million. …. for example, in December, we announced that we would no longer be offering admitted personal property homeowners policies in the state of California. We cannot maintain our current level of aggregation in the state nor have we been able to achieve any profitability from this line of business.

Peter devoted a solid four paragraphs to the challenges the insurer is facing due to changes that have already happened in the environment.

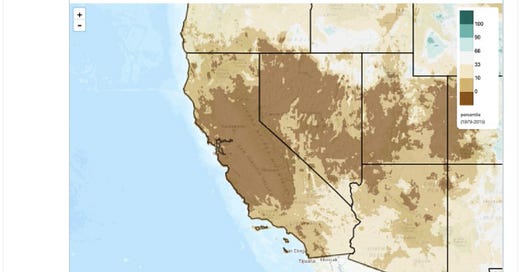

As mentioned before, the West is experiencing an extraordinary dry spell, and fires this year may exceed those seen in the last few.

There have been two recent reports that highlight some developments and risks: Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021 and 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report.

From the “megadrought” paper:

A previous reconstruction back to 800 CE indicated that the 2000–2018 soil moisture deficit in southwestern North America was exceeded during one megadrought in the late-1500s. Here, we show that after exceptional drought severity in 2021, ~19% of which is attributable to anthropogenic climate trends, 2000–2021 was the driest 22-yr period since at least 800. This drought will very likely persist through 2022, matching the duration of the late-1500s megadrought.

This emerging megadrought, spanning 2000–2021, has been the driest 22-year period since the year 800 and 19% of the drought severity in 2021 can be attributed to climate change.

Park Williams put together a twitter thread on the paper that is easily readable. I really encourage you to take the 5 minutes to scroll through.

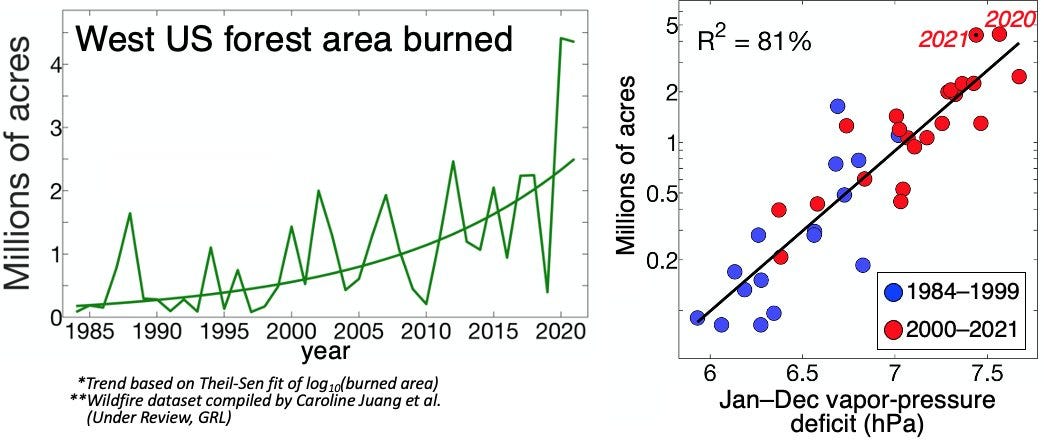

This chart in particular caught my eye. Acres burned appear to be a linear function of vapor pressure deficit. The annual change in burned acres is fit as a log function; is 2021 an outlier and acres burned will revert to 1-2mm acres burned, or is it a precursor of further non-linear growth.

So wildfire risk has broken HNW admitted property insurance. Wonder what’s next (keep reading).

The “2022 Sea Rise” report is a technical piece, and written in part in bureaucratic jargon that needs deciphering. Sea-level rise is one of the most tangible present-day effects from human-caused climate change that is being felt in the U.S., with coastal flood events becoming far more common and damaging in just the past few decades.

Axios does a nice job summarizing:

The assessment projects an additional 10- to 12-inch increase in sea levels by 2050, with higher amounts in some parts of the country due to changes in land height and ocean currents. … The East and Gulf coasts are expected to see a greater rise in sea level than the West Coast, for example

The report warns that the sea level rise through 2050 will dramatically escalate the frequency and severity of coastal flooding, including so-called "sunny day" flooding at times of high tide in areas such as Charleston, S.C. and Miami.

The report says that nationally, a "flood regime shift" is projected to occur by 2050, with moderate high tide flood frequencies to increase by more than a factor of 10 nationally, along with a five-fold increase in major high tide flood frequencies.

It notes that "significant consequences" are in store for coastal infrastructure, absent new efforts to reduce risk exposure.

Ben Strauss, CEO and chief scientist of the research group Climate Central, said, "Just one foot of sea level rise will change a lot of American lives." "Our national sea level threat has started slowly, but it's going to accelerate like a rocket," Strauss added.

Again, the risks and damage are non-linear both because the change may be non-linear, but largely due to the proximity of population and infrastructure to the area of threat (sea rise).

MSCI

The MSCI approach to measuring climate risk has come under criticism. Bloomberg, in an article The ESG Mirage, states:

MSCI, the largest ESG rating company, doesn’t even try to measure the impact of a corporation on the world. It’s all about whether the world might mess with the bottom line.

The article is pretty scathing. Bloomberg further notes:

MSCI dominates a foundational yet unregulated piece of the business: producing ratings on corporate “environmental, social, and governance” practices. BlackRock and other investment salesmen use these ESG ratings, as they’re called, to justify a “sustainable” label on stock and bond funds. For a significant number of investors, it’s a powerful attraction.

Yet there’s virtually no connection between MSCI’s “better world” marketing and its methodology. That’s because the ratings don’t measure a company’s impact on the Earth and society. In fact, they gauge the opposite: the potential impact of the world on the company and its shareholders.

This topic came up on MSCI’s earnings call, with a question from Alex Kramm of UBS.

It seems like recently, there's been an increase of autocalls in whatever call it popular press around ESG, about firms like you and maybe how some of these ESG scores are not really a reflection of what people think, they're buying or getting into when they're investing in ESG products.

MSCI’s CEO defends the ratings by noting:

[W]e at MSCI serve a large number of different type of investors. In ESG and in climate, we serve investors that are looking to integrate ESG and climate considerations into their investment process and, therefore, they only focus on financial risk associated with ESG controversies and ESG issues or climate issues in security selection or pricing of -- in their portfolios, right? The second type of investors are impact investors. And those are very different than the ones that are looking for financial metrics only. … The third type of investors is value-based investors, religious organizations and the like in which they want to -- they only want to be investing in what they believe in …

He further explains that the second and third type of investors

… are investors that are looking to, as the name says, make an impact in what they do, and some of them may be willing to give up returns.

He then sort of says out loud the private stuff:

And many of them (investors) have indicated that it is very incredible to have people that think that they can take -- feel sharing money and go out and find social causes where they feel to share the money, when that is not part of their mandate. So a lot of what these articles have been allocating is for people like you and others on this call to go out and invest and get lower returns on the basis of helping different parts of the world. … And that is -- that's not what the reason is in your mandates on how people earn money. So there are others that do that, and we serve all kinds of investors.

So somehow he is asserting that one rating can do two distinct things: measure the risk of ESG on the company, and measure the risk of the company to greater society. That doesn’t work.

Asset manager Capitalism & ESG

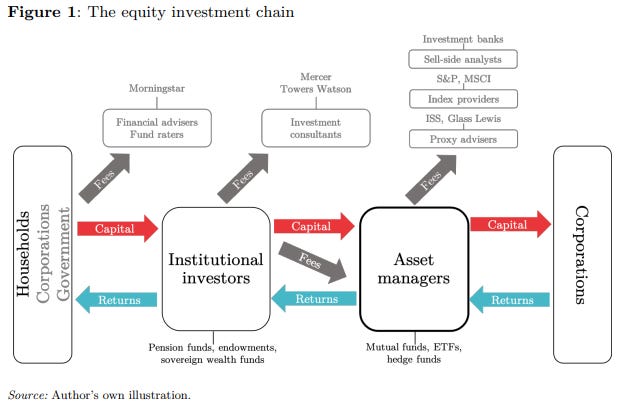

Paul Kedrosky highlighted an interesting Adam Toose chartbook post The rise of asset manager capitalism and the financial crisis of 2008 that goes on to describe the work of Prof Mark Blyth, who in turn leads us to the work of Benjamin Braun on changes in market structure, and in particular a very interesting paper titled Asset Manager Capitalism as a Corporate Governance Regime. Stick with me, I know that’s a long chain. In the paper, he asserts:

[E]merging asset manager capitalism is dominated by fully diversified shareholders that lack direct economic interest in the performance of individual portfolio companies.

My central argument is that this new ‘asset manager capitalism’ constitutes a distinct corporate governance regime [with] four hallmarks characterize this new corporate governance regime.

First, U.S. stock ownership is concentrated in the hands of giant asset managers.

Second, due to the size of their stakes, asset managers are, in principle, strong shareholders with considerable control over corporate management.

The third hallmark is that large asset managers are “universal owners” that hold fully diversified portfolios (Hawley & Williams 2000).

Finally, as for-profit intermediaries with a fee-based business model, asset managers hold no direct economic interest in their portfolio companies.

Whereas under the shareholder primacy regime the dominant shareholders sought to maximize the stock market value of specific firms, under asset manager capitalism the dominant shareholders are incentivized to maximize their assets under management.

Toose goes on to summarize

Asset managers are mediated owners. They are mediated also as a result of the sheer size of their portfolios. They are radically diversified, owning slices of practically every corporation worth anything. But their bulk means that their ability to exit stock is limited. They are simply too big.

Like a robber baron, BlackRock has achieved a high concentration of ownership. Unlike a robber baron it has a huge diversification of what it owns and a limited interest in any particular bit of its portfolio. This somewhat paradoxical state of being into everything and unable to get out, gives rise to the idea that asset managers are what is called “universal owners”1.

Toose goes on to link “universal ownership” to ESG, citing From Passive Owners to Planet Savers? Asset Managers, Carbon Majors and the Limits of Sustainable Finance by Baines and Hagar. Baines and Hagar, in investigating the role of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, finds:

[T]he Big Three much more often than not oppose rather than support shareholder resolutions aimed at improving environmental governance. Notably, this is even the case with the Big Three’s environmental, social and governance funds.

OK, so far not so surprising.

Where it gets interesting is when Toose links this to the comments and advocacy of Larry Fink of Blackrock.

What BlackRock wants is exorbitant. It wants the public balance sheet to step in backstop any risks that asset managers might be running in making serious ESG investments. And because BlackRock is a huge universal owner, when it asks for a public backstop it means the public balance sheet of the world - no kidding! Larry Fink of BlackRock has made clear, repeatedly, that he wants all the capable governments of the world to pitch in to increase the loss absorption capacity of the IMF and World Bank balance sheets.

Fink is advocating for the public sector to backstop and “derisk” investments made by the private sector (read asset managers) to accomplish climate goals, and implicitly threatening to withhold investment if these ‘public/private partnerships” do not occur.

The governments appear, in part, willing to do this and, in part, are pushing back by pushing for increased transparency and public pressure through disclosure and regulatory stress tests. An interesting take on this “political economy” negotiation is The Wall Street Consensus at COP26 by Daniela Gabor which is cited by Toose. I’m not an expert here, but this really sounds like the “inside baseball” take; either that or I have jumped the shark to become a climate change conspiracy theorist!

Gabor summarizes (and here we link back to MSCI):

The big takeaway from COP26 is therefore not that private finance will go to great lengths to portray its systemic greenwashing as climate activism. This is rather predictable. The more worrying development is that the state is not only prepared to let finance get away with it, but is willing to subsidize the climate destruction guaranteed by this path.

Universal ownership: exploring opportunities and challenges, Mercer Consulting 2006