The Perspective is going on a break as I take a vacation in Spain. See you in October.

Leverage

More on the basis trade

The BIS September 2023 Quarterly Review is out. They have a box titled Margin leverage and vulnerabilities in US Treasury futures highlighting the risks of the basis trade. Matt Levine commented on the “worry” in People Are Worried About the Basis Trade. Matt sure can write a lot - whew. I discussed that this concern in the Sept. 5th Perspectives and in the Sept 15 Perspectives first showed in a Fed staff paper Recent Developments in Hedge Funds’ Treasury Futures and Repo Positions: is the Basis Trade “Back"? It starts by regurgitating the Fed paper (with some nifty graphs):

Speculative positions by leveraged investors in US Treasuries are back. Over recent months, leveraged funds have built up net short positions in US Treasury futures of about $600 billion (Graph A1.A), with more than 40% of the net "shorts" concentrated in two-year contracts (Graph A1.B).icon These funds had been at a comparable level of net shorts in the run-up to the repo market turmoil of September 2019 (marker a) and the US Treasury market dislocations of March 2020 (marker b).

It does add to the discussion with:

A less discussed aspect of the leverage involved in the cash-futures basis trade stems from futures markets. … The ratio of futures contract value relative to the IM determines the allowed leverage. … Leverage in actual US Treasury futures was very high before the pandemic, at about 175x and 120x on average for five- and 10-year Treasuries, respectively (Graph A1.C). It has declined since 2021, as the increased volatility in the US Treasury market has led to higher required IMs, but is still elevated, at about 70x and 50x, respectively.

Given these experiences, the current build-up of leveraged short positions in US Treasury futures is a financial vulnerability worth monitoring because of the margin spirals it could potentially trigger. While this channel was well recognised in the March 2020 "dash-for-cash" episode, other factors garnered more attention in the context of the September 2019 repo market stress. Yet the margin deleveraging in August 2019 may have presaged the funding market disruptions that followed a month later. Margin deleveraging, if disorderly, has the potential to dislocate core fixed income markets.

Private Equity NAV Borrowing

I’ve said before how the basis trade was one of the regulators favorite worries. Perhaps they are looking in the wrong area. The FT has been recently highlighting the issue with two articles: Buyout groups raise debt against portfolios to return cash as dealmaking slows, and ‘Defending the portfolio’: buyout firms borrow to prop up holdings.

The first article states

Private equity fund managers are borrowing against asset portfolios to return cash to investors as they struggle to exit investments, adding another layer of debt to the loans financing their corporate buyouts.

In a notable transaction last year, Goldman Sachs and Carlyle’s internal capital markets unit helped arrange a loan exceeding €1bn for Carlyle late last year, securing it against assets in the US firm’s fifth European buyout fund, according to two people with knowledge of the borrowing. The loan was used to send money back to Limited Partners.

While the second gives a different rational:

Private equity firms have started to borrow against their funds to backstop overly indebted portfolio companies, a new financial engineering tactic meant to cope with higher interest rates and a slowdown in dealmaking.

The manoeuvres, which lenders have dubbed “defending the portfolio”, have cropped up as many older private equity funds run low on cash just as the companies they own struggle with their own debt loads

Last month Vista Equity Partners, a private equity investor focused on the technology industry, used a NAV loan against one of its funds to help raise $1bn that it then pumped into financial technology company Finastra, according to five people familiar with the matter.

The equity infusion was a critical step in convincing lenders to refinance Finastra’s maturing debts, which included $4.1bn of senior loans maturing in 2024 and a $1.25bn junior loan due in 2025.

Who else is doing the deals?

The Financial Times has previously reported that firms including Vista, Carlyle Group, SoftBank and European software investor HG Capital have turned to NAV loans to pay out dividends to the sovereign wealth funds and pensions that invest in their funds, or to finance acquisitions by portfolio companies.

The borrowing was spurred by a slowdown in private equity fundraising, takeovers and initial public offerings that has left many private equity firms owning companies for longer than they had expected. They have remained loath to sell at cut-rate valuations, instead hoping the NAV loans will provide enough time to exit their investments more profitably.

Guess those reassurances about the amount of dry-powder weren’t worth much. Dry powder is not uniformly distributed.

Large banks like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan have long provided NAV loans, but there has been a growing number of lenders entering the space broadening the usage of the debt. Banks now compete with a specialised group of private NAV lenders like 17 Capital and Whitehorse Liquidity Solutions, in addition to new entrants to the marketplace like private lenders Apollo Global, Ares and HPS.

PIK NAV loans…

The terms of recent loans viewed by the Financial Times showed that borrowers have agreed to pay at least 7 percentage points above benchmark rates and normally ask for payment-in-kind features that give them the option of paying interest with resources other than cash.

Pitchbook may have been the first to notice the trend, writing back in May GPs quench thirst with NAV financing as liquidity dries up

Deal volume involving NAV financing soared 50% in the 12-month period ending in September 2022, and the average size of NAV facilities provided in the same period grew by 40%, according to 17Capital.

During Q1 2023, the demand for NAV facilities has grown even faster as a result of the tough PE exit environment and the lack of traditional financing sources amid bouts of volatility.

And yup, there’s a bank capital rule angle:

Big banks such as Citigroup have significantly cut back on offering subscription lines of credit—which fund managers use to narrow the gap between making investments and calling capital from LPs—to adhere to the new capital requirements imposed by the Federal Reserve. The constraint in that market could push more PE funds to use NAV financing as a substitute.

So this seems to be a twist on what happened during the GFC. Then, investors were selling off their commitments at a discount to raise liquidity. Now, the liquidity is raised at the fund level, perhaps alleviating the immediate stress on the investor, but resulting in a more leveraged position with higher financing costs in a weaker economy. Still, from a lenders point of view, lending against a portfolio is probably safer than lending against an individual exposure; as Matt Levine puts it

A basket of options is worth more than an option on a basket

Non-bank financial institution leverage

One of my favorite questions, both as a regulator and as a risk manager, is how would you run things in the absence of the regulatory rules? For example, how much capital do you think you really need to run the organization safely?

I came across an interesting paper presented out at BYU’s Red Rocks Finance Conference: Banking without Deposits: Evidence from Shadow Bank Call Reports

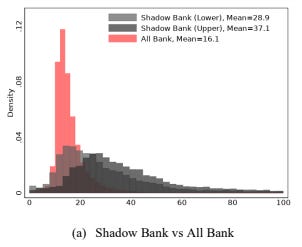

We ask how much leverage banks would choose in the absence of safety nets tied to insured deposits. Using uniquely assembled data on capital structure decisions of shadow banks – intermediaries that provide banking services but are not funded by insured deposits – we document five facts.

Shadow banks use twice as much equity capital as equivalent banks but are substantially more leveraged than non-financial firms.

Leverage across shadow banks is substantially more dispersed than leverage across banks.

Like banks, shadow banks finance themselves primarily with short-term debt and originate long-term loans.

Shadow bank capitalization decreases substantially with size. Bank capitalization hardly changes with size. Uninsured leverage, defined as uninsured debt funding to assets, increases with size for both banks and shadow banks.

Average interest rates on uninsured debt decline with size for banks and shadow banks.

Here is a comparative distribution graph of Tier 1 equity ratios.

More Reading

The IMF has published Good Supervision: Lessons from the Field.

Keeping banks safe and sound hinges on good supervision. The bank failures of March 2023 precipitated questions about the effectiveness of supervision. This paper reflects on lessons learned from this banking turmoil and reviews global progress in delivering effective supervision over the past ten years. It finds progress in areas like risk monitoring, stress testing, and business model analysis. Yet, progress has also been hampered by deficiencies in supervisory approaches, techniques, tools, and (use of) corrective and sanctioning powers, as well as by unclear mandates, inadequate powers, and lack of independence and resources. Overcoming these deficiencies requires supervisors to improve their own performance and other policy makers to contribute to ensuring vigilant, independent and accountable supervision.

Adrian Woridge has published an interesting opinion piece: Capitalism and Classical Liberalism Are Headed for Divorce (Bloomberg)

The founders of modern liberalism had no doubts about the positive links between philosophical liberalism and capitalism (or “commercial society” as they would have dubbed it).

The building blocks of both capitalism and liberalism are identical: individual rights in both law and custom, freedom of choice in both politics and the marketplace, the separation of politics from economics, freedom of conscience and debate.

Yet it is important to add a qualification: If you cannot have liberalism without capitalism, you can certainly have capitalism without liberalism.

Today we are witnessing a degree of economic concentration that we have not seen since the late 19th century: a collection of superstar companies is consolidating their power at the heart of the global economy and exercising enormous political influence at home and abroad.

Acton’s law can be seen in the growing willingness of respectable companies to engage in practices that were once confined to the backstreets.

Liberalism was born in the fight of outsiders against insiders: Liberals were usually humble radicals who wanted to subject decadent institutions to fair competition. … Today’s capitalism is honeycombed with insider deals.

The idea of linking remuneration to stock was supposed to exert discipline on managers by forcing them to act like entrepreneurs, exposing them to the downside as well as the upside of capitalism Instead, managers used their inside power to game the system by writing contracts that protected them from the downside (“golden parachutes” and the rest) while giving themselves the right to sell stock at a time of their own choosing.

This system of insider privilege poses a profound threat to a central liberal principle: meritocracy.

Information capitalism embodies a serious threat to the liberal notion of a rational individual. It keeps us constantly exposed to “hidden persuaders” that beep and flash at us from our phones wherever we go. It reduces our sense of agency as employers watch our every move over our shoulders.

Agree or disagree, it is an article worth wrestling with.

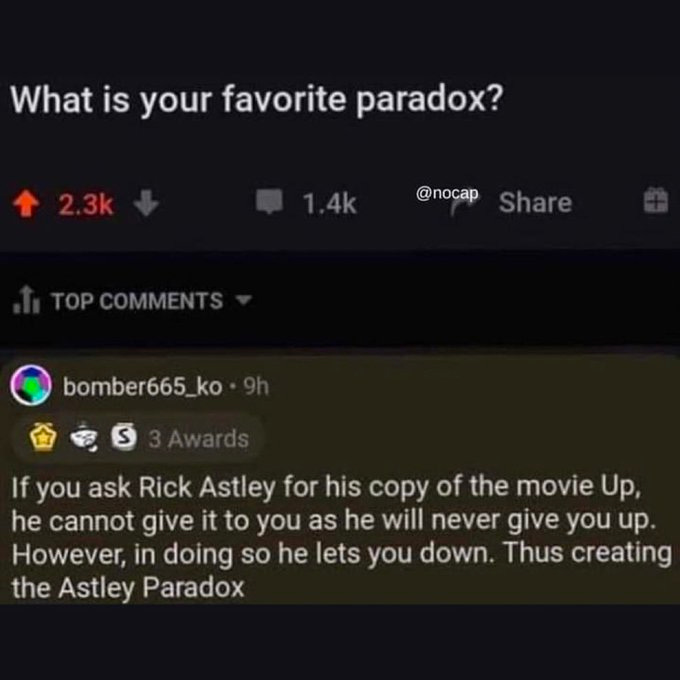

The Ashley Paradox

While I’m On Vacation

The Rest of the Year in U.S. Bank Regulation (Bank Reg Blog)