Perspective on Risk - July 31, 2023

Deposit Beta (and Gamma); Regulation Crowded Out Risk Management? Following Up; Artificial Intelligence; Great Podcasts

Recession

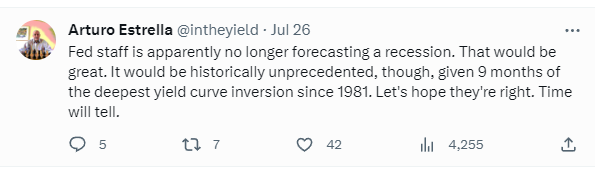

The popular consensus is that there will be no recession. I stand with the guy who wrote the book on The Economics of Recession, and the economist who with Fred Mishkin developed the yield curve indicator, my former colleague Arturo Estrella. As I stated in the July 4, 2023 Perspective, we are now within the recession window.

I also like to listen to Lacy Hunt. He’s one of the more blunt and fun economists to follow. He’s a bond manager and a deflatioista, and has been wrong on inflation before. The Texans are always iconoclastic.

Lacy believes we are in for a credit crunch that will lead to recession. Jump ahead to about 10:00 to hear his thesis. Lacy is clearly in camp ‘lags.’

We are still within the normative lags

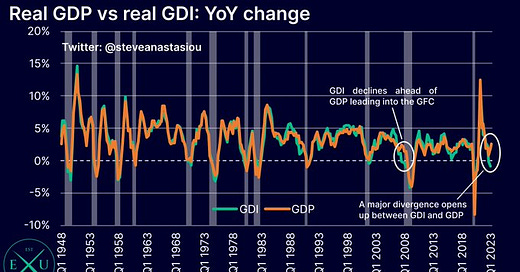

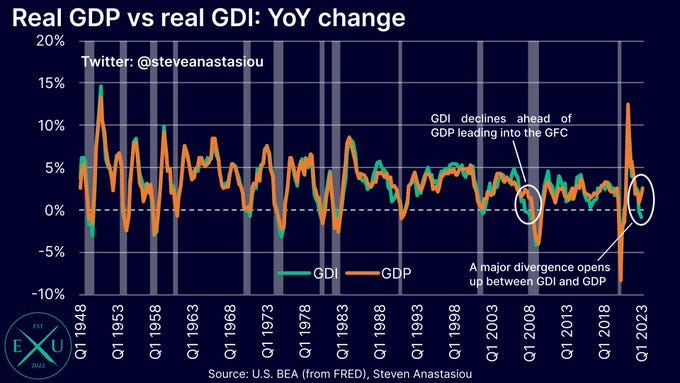

Further. Gross Domestic Income (which I think in theory should match GDP except for discrepancies in measurement) is already negative.

And David Lubin writes at Chatham House The global trade recession may have already started

The annual growth rate of global import volumes turned negative late last year, remained negative in early 2023 and there are few reasons to think that things will improve.

I may be succumbing to confirmation bias. We’ll see.

Deposit Beta

One of my first leadership assignments while an examiner at the Fed had the task of reviewing bank’s interest rate risk positioning and modeling. At the time, Board of Governors staff were also trying to develop a capital charge for interest rate risk.

One of the first things you encounter either as an examiner or as someone trying to develop a capital charge is the challenge of treating demand deposits. Contractually, they are callable on demand; but practically, banks often asserted (with some evidence) that the deposits were “sticky” and hence the duration of assets you could match against these liabilities could be longer. From a banker’s perspective this only made good economic sense.

In recent years, the industry likes to talk about “deposit betas.’ Deposit beta1 measures the sensitivity of a bank's deposit cost to changes in the short-term interest rate. If Treasury rates go up by 1%, how much do I have to raise my deposit rates to avoid outflows.

Back at that time, before the internet, betas tended to make sense. Liquidity and bank runs were thought of along a different dimension. So were credit problems at a bank. We were in a world of insured deposits, and these tended not to run.

As late as 2004, researchers stated:

Many banks replicate non-maturity deposits with a static portfolio of straight bonds by minimizing the tracking error between the cash flows of the hedge portfolio and those of the account during a sample period (Kalkbrener and Willing (2004)).

The assumption here, therefor, is that the duration of demand deposits is stable / deposit betas are not stable.

Tensions in the modeling of interest rate risk can be seen in 1996’s Joint Policy Statement on Interest Rate Risk. Examiners and supervisors were beginning to take an economic value perspective to the review of interest rate risk (rather than their historical focus only on net interest margin) and had proposed a model to assess the interest rate risk of a bank and/or assess a capital charge.

The industry and the regulators were focused on the optionality on the asset side of the balance sheet, and on the effective maturity of non-maturity deposits (the industry of course was arguing the regulators view was too short). This comment summarizes the key debate:

In particular, some industry commenters have stated that if the agencies adopted assumptions that understated the effective maturities of a bank's non-maturity deposits, it could induce a bank to inappropriately shorten its asset maturities, leave the bank exposed to falling interest rates, and unnecessarily reduce its net interest margins. The agencies, however, are also concerned that an assumption that overstated the maturity of these deposits could mistakenly lead banks to extend their asset maturities, leaving them exposed to rising interest rates and significant loss in economic value.

There was no discussion of the options in liabilities.

(and gamma)

In reality, there are significant sources of gamma in demand deposits.

Similarly, and more broadly, if one accepts the industry argument that the typical duration of non-maturity options is greater than a day, then one needs to recognize that the customer has the right to call away their deposit at a moments notice.

In the case of SVB, we saw that there was clearly a credit-related gamma; as the knowledge or perception of SVB’s unrealized losses grew, depositors called away their deposits by moving relationships to other financial institutions.

Similarly, there is the risk that the deposits are called away due to better returns on alternative investments.

Modeling became a tad more sophisticated beginning around 1998; however much of modeling, even when done within a proper analytical framework, with hindsight, seems obsessed with justifying previously observed behavior (deposit rate stickiness; asymmetric rate adjustments). Said another way, they try to fit past data rather than starting from first principals.

Some of the earliest application of derivative modeling to demand deposits was done by Jarrow and van Deventer2. van Deventer was the owner of Kamakura, which at the time was the most sophisticated platform for economically valuing firm’s assets and liabilities. They wrote in 1998:

The hedging of the demand deposit liability, in particular, is a relatively unstudied issue of significant practical importance.

This paper uses the interest rate derivatives technology of Heath et al. (1992) to value both demand deposits and credit card loans.

Demand deposit liabilities … are seen to be equivalent to a special type of exotic interest rate swap with amortizing/extending principal.

I suspect most people did not fully understand the optionality in the “amortizing/extending principal.”

I’d also cite the work of Fed Board economist Richard O’Brien3. His paper explicitly addresses deposits in an option-theoretic approach.

A valuation model is developed within an interest rate contingent claims framework to estimate NOW account and MMDA premiums and interest rate risk for a sample of commercial banks.

Both Jarrow and O’Brien model deposit rates against competing Treasury rates, but since they are fitting to historical data they find rather slow adjustment effects.

The first paper that I could find that explicitly models the customers withdrawl rights is 2015’s Identifying, valuing and hedging of embedded options in non-maturity deposits.

Valuing and hedging non-maturity deposits like saving accounts or demand deposits – the main funding source for a majority of banks – are not straightforward tasks because the interaction of the bank’s discretionary pricing and the depositors’ withdrawal right generates significant option risk due to implicit non-linear factor exposures. The current literature and regulatory framework on non-maturity deposits largely ignore inherent non-linear factor exposures and therefore the resulting option risk. Different assumptions on pricing and depositors’ behavior result in different non-linear risks, valuations and hedging schemes.

I clearly reject the widespread notion that “the duration of these accounts is relatively constant,” as hypothesized by Wilson (1994).

A replicating hedge portfolio of straight bonds “that has the same price and the same delta profile as the non-maturing liabilities,” as suggested by Kalkbrener and Willing (2004) for a savings account, would ignore the inherent volatility risks stemming from embedded option risks.

But going into the recent regional bank kerfuffle, no one seems to have recognized that the speed of adjustment to market rates would now be faster, or that the level of volatility was important in their deposit pricing and valuation..

In a recent OddLots4 interview with Scott Hildenbrand of Piper Sandler, he made the following observations:

There are no contractual liabilities on a bank’s balance sheet anymore

Forever, [bank deposit beta] has been 30-50%

Dollars can now move so much faster due to technology and demographics. …

You need to think about [how different generations] view a bank. … There’s a loyalty/trust matrix.

A lot of loyalty in my father’s generation, but not a lot of trust. He’s going to take a check [an immediately deposit it in a bank branch].

Then you think about the generations below, there’s a ton of trust, they’ll move money around on phones, they don’t even know the name of the bank they’re banking at, there’s no loyalty/

One interesting question is whether the speed with which the Fed has raised rates somehow contributed to the faster adjustment. As an aside, in the proposed capital charges discussed above in the Joint Policy statement above, we were talking about capitalizing banks for a 200bp shock over one year. And that was seen by the bankers as too extreme.

Now, in past Perspectives I have written that I was worried that the regulators current desire to have banks realize for bank capital purposes the unrealized losses in their asset portfolio risks further playing into the asymmetrical accounting treatment of assets and liabilities. I’ve suggested that banks should be allowed to include the gains/losses from value changes on the liability side. But as was seen in 1996, reaching consensus will be hard; and adjusting for credit gamma and the interest rate gamma from alternative investments will make this challenge virtually impossible.

Regulation Crowded Out Risk Management?

I’m increasingly of the opinion that supervisory requirements have hampered risk management. There are two types of firms; those that will take risk management seriously, and those that will just follow regulatory proscriptions.

For firms that WOULD take risk management seriously, though, there are finite resources and to the extent that there are regulatory mandated stress tests they will crowd out other risk management work that a firm might find more useful given their distinct risk profile.

For those who worked with me at the Fed, you will remember that I always thought there were three levels of employees in the supervision track: 1) bank examiners, 2) bank supervisors (who understood that exams was but one tool of the supervisor), and 3) central bankers (who understood that central banks supervised banks to make sure the monetary policy transition mechanism worked).

The initial 2007/8 series of SCAP stress tests were driven by the third group. They were done to quantify FOR THE MARKETS the capital strength or hole in systemically important bank balance sheets. And, importantly, and implicitly, firms that were able to fill these capital holes would NOT be closed by the regulators. There was an unstated agreement.

Once the capital holes were filled and banks made investable again, enamored with the perceived effectiveness of the effort, and willfully ignorant of the costs, the stress tests were cemented into place by the second group - the supervisors. Some supervisors liked this precisely because it took away some of the discretion inherent in the bank examination process. Things were standardized; rules were written; bureaucracy wins.

But as the health of the banking sector improved, the connection between central banking and bank supervision in the construct of the stress test waned. The central bankers, from day 1 of the SCAP, were always leery about the ‘signaling’ effect of proscribed rate paths, reaction functions and the like. This could be why the stress test was not redesigned to test an up-rate shock, something I would note we did at my former firm before it was crowded out by the regulatory work.

As I wrote in a previous perspective, the stress test has become a goal-seeking exercise whereby regulators determine the level of capital in the banking systems, and in part try to influence the cost of credit.

I think the Fed and the other regulators are going in precisely the wrong direction by looking to expand the population of banks required to complete the regulatory stress test, and as Barr has suggested, possibly increasing the number of stress tests.

Instead, the regulators should look to reduce the burden of regulatorily mandated stress tests while increasing the examination attention on insuring firms have robust risk management. SVB did not fail because it did not run the stress test; it failed, in part, because it did not have a sufficiently robust risk management function to bring forward information and challenge the revenue producers: a supervision tale as old as time itself.

Scrapping KYC/AML

I don’t know if it’s a trend, but the economist Alex Tabarokk (Marginal Risk blog) has highlighted two papers advocating that we scrap our existing KYC/AML laws..

The first was from an Australian law Professor Ronald Po: Anti-money laundering: The world's least effective policy experiment? Together, we can fix it. Po:

finds that the anti-money laundering policy intervention has less than 0.1 percent impact on criminal finances, compliance costs exceed recovered criminal funds more than a hundred times over, and banks, taxpayers and ordinary citizens are penalized more than criminal enterprises.

Necessarily applying a broad brush, the current anti-money laundering policy prescription helps authorities intercept about $3 billion of an estimated $3 trillion in criminal funds generated annually (0.1 percent success rate), and costs banks and other businesses more than $300 billion in compliance costs, more than a hundred times the amounts recovered from criminals.

… If authorities recover around $3 billion per annum from criminals, whilst imposing compliance costs of $300 billion and penalizing businesses another $8 billion a year, it is reasonable to ask if the real target of anti-money laundering laws is legitimate enterprises rather than criminal enterprises.

The scale of the problem not addressed by “solutions” repeatedly “fixing” the same perceived issues suggest that blaming banks for not “properly” implementing anti-money laundering laws is a convenient fiction.

The second screed he highlights is from the Twitter account of Bruce Felton. This is more of a libertarian screed than a thoughtful paper. As with Po, Felton argues that the benefit has not been shown:

The 1990s to the post 9-11 Patriot Act (which was a horrible law) saw a radical increase in AML /KYC requirements. These seem to get worse every year.

Are major criminals somehow stopped by this? Has it stopped crime? Even if it did, is it worth burdening millions of firms and billions of people with paperwork and procedures that slow down commerce? Shouldn’t efforts be made to go after the actual criminals rather than encumbering the entire world with an inefficient compliance regime?

The US (and by extension much of the world due to our influence) is sacrificing jobs, innovation and opportunities by chasing an extremely ineffective and indirect compliance regime.

Perhaps I just noticed these because it is quite similar to the argument I just made on mandated stress testing. Don’t know.

Artificial Intelligence

So my first observation is that, while LLMs are imperfect, so are humans. And they are still more intelligent than the average human; faster, wider breath of knowledge, etc.

Beyond Turing

The Large Language Models have passed the Turing test, so of course we must move the goal posts. ChatGPT broke the Turing test — the race is on for new ways to assess AI

The world’s best artificial intelligence (AI) systems can pass tough exams, write convincingly human essays and chat so fluently that many find their output indistinguishable from people’s. What can’t they do? Solve simple visual logic puzzles.

Prediction: this will be solved in less than six months.

The Voight-Kampff test

The Voight-Kampff test is a fictional psychological assessment used in the science fiction universe of Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" and later popularized by its film adaptation, "Blade Runner" (1982). The test was designed to distinguish between humans and humanoid androids, known as "replicants," who are nearly indistinguishable from humans in appearance and behavior.

Every major LLM can pass the Voight-Kampff test. Pi was particularly good.

I also wonder about how our brains work; what is consciousness? Are we just sophisticated LLMs, filling in the next word of phrase as we go along? Is this why some people make up so much shit?

Would You Pass the Turing Test? Influencing Factors of the Turing Decision

In two studies, we used the Turing test as an opportunity to reveal the factors influencing Turing decisions.

In our first study, we created a situation similar to a Turing test: a written, online conversation and we hypothesized that if the other entity expresses a view different from ours, we might think that they are a member of another group, in this case, the group of machines. Our results showed a significant relationship between the Turing decision and the attitude difference of the conversation partners. The more difference between attitudes correlated with a more likely decision of the other being a machine.

With our second study, we wanted to widen the range of variables and we also wanted to measure their effect in a more controlled, systematic way. Our results showed that logical answers, proper grammar, and similar attitudes predicted the Turing decisions best. We also found that more people considered mistaking a computer for a human being a bigger problem than vice versa and this choice was greatly influenced by the participants’ negative attitudes towards robots.

Almost half of our participants (42%) decided that their conversational partner (that was in every case a human being) was a computer program.

Artificial Intelligence in Insurance

For those interested, Swiss Re, in their Sonar series, has published an interesting set of articles under the common heading “Decrypting AI in Insurance.” A good set of reads if this is of interest.

Benefits and use cases of AI in insurance (Swiss Re)

The Future of AI in Insurance (forthcoming)

Shorts & Updates

For those who liked the last Perspective on climate change, Prof. Rahmsdorf has authored a very nice twitter stream on the AMOC events. If you want to track extreme heat situations in the US, check out Heat.gov

I was excited, but skeptical, when I read about the latest claims about room-temperature superconductivity. This would be a global gamechanger if true. Unfortunately, looks like it isn’t true. Prediction markets only at 11-17%, and the coauthor seems to be disputing the claims.

The National Association of Realtors has stated that “the office vacancy rate reached a new record high at 13.1% at the end of the year's first half.” Full report is available at the link.

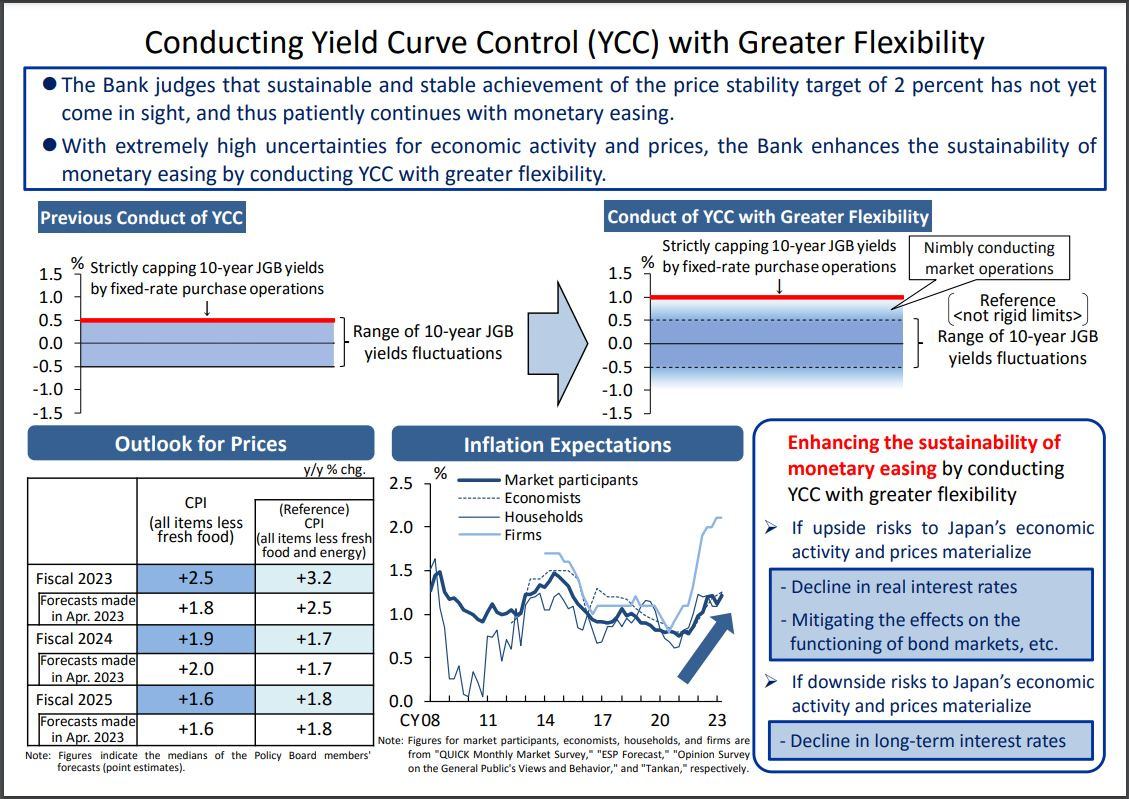

The Bank of Japan on Friday loosened its yield curve control (YCC) policy. This is worth thinking about. No good link (send me anything you find useful here).

The Yale Journal of Financial Stability folks have published a paper mostly from Fed economists A Macroprudential Perspective on the Regulatory Boundaries of US Financial Assets. Seems pretty important. Haven’t read it yet, but it’s on this week’s reading list (ahead of the capital rules). If you’re playing along at home, send me your thoughts on the paper and maybe we can have a dialogue.

Oh, and the Fed, FDIC and OCC have put out the new capital rules for comment. Agencies request comment on proposed rules to strengthen capital requirements for large banks. No, I haven’t read them. Probably should at some point if I’m going to keep commenting. Ugh. Nothing worse than reading bank capital rules. The broader issue I will be interested in is how this changes the boundary between banking and non-bank activities.

Podcasts

These two podcasts are terrific. Only Kahneman is on Spotify.

Episode 022: Deciding, Fast and Slow with Dr. Daniel Kahneman (Alliance for Decision Education podcast)

The lightning onset of AI—what suddenly changed? An Ars Frontiers 2023 recap (Youtube Ars Technica)

Happy Birthday to me.

The term deposit beta was introduced in The Deposits Channel of Monetary Policy in the Quarterly Journal of Economics Volume 132, Issue 4, November 2017

The arbitrage-free valuation and hedging of demand deposits and credit card loans, Journal of Banking and Finance Volume 22, Issue 3, March 1998, Pages 249-272

The Massive Shift Underway in the US Banking System, OddLots July 27, 2023

Happy Birthday!