Perspective on Risk - Sept. 24, 2024

Cover the over; A Failure of Supervision; CFPB Uses The Death Penalty; Future of Bank Supervision (2); Unintended Effects; ECB Supervision; Stress Testing; Populism

Cover The Over

“This is not a middle-ground re-proposal,” said Jeremy Kress, a former Fed lawyer who now teaches at the University of Michigan. “On nearly every point of contention, this is a capitulation to the banks.”

The real risk from the ignominious end of the endgame is that the world is bound to notice that the swing of the regulatory pendulum has changed direction.

When I joined AIG, one of the first things I was asked is when the Basel III rules would happen. This was 12 years ago. My counsel then, up until today, was “take the over.” Didn’t matter what date was proposed.

Now the agencies have revised yet again the rules, and they’ve been neutered sufficiently that I think the banks will stop the fight. They say large bank capital will increase by 9%, but that is before the banks reoptimize to the new set of rules. It will be less.

In some important cases, they’ve gone below what a straight implementation of Basel III would have required. From Gov. Barr:1

With respect to loans to retail customers, I intend to recommend that we adopt the Basel standard, with two exceptions – first, we would lower the capital requirements for credit card exposures where the borrower uses only a small portion of the commitment line, and second, we would lower the capital requirement for charge cards with no pre-set credit limits.

I intend to recommend that the Board not adopt the capital treatment associated with minimum haircut floors for securities financing transactions.

I plan to recommend that we significantly lower the risk weight for tax credit equity funding structures, given the lower inherent risk in these structures compared to many other equity investments.

I plan to recommend that the Board adjust the capital treatment for client-cleared derivatives activities by reducing the capital required for the client-facing leg of a client-cleared derivative.

How Wall Street won ‘capitulation’ from the Federal Reserve on new bank rules (FT)

US regulators are not the only ones having to embrace humility when it comes to implementing the so-called Basel III Endgame — the final rules tied to an international effort that emerged in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to shore up the banking sector.

Globally, there is a retreat among the financial system’s top cops, who have pared back proposals in response to fervent pushback from the very institutions they oversee. The UK this week is set to join the US and EU in making concessions and delaying the eventual implementation of their own rules.

Basel III: The US has started a race to the bottom (FT)

In the past, the US authorities have tended to take a two-tier approach to the global standards emanating from Bank for International Settlements in Basel, implementing them in a gold-plated fashion for the very largest dozen or so banks but leaving the majority of their system completely untouched. This allowed the Fed to claim it was among the world’s toughest regulators, while avoiding too much complaint from the powerful domestic savings bank lobby. This strategy seems to have been abandoned.

Global regulators will certainly notice that the US has started a race to the bottom — the Bank of England’s announcement of its own endgame proposals already makes several references to “international competitiveness” and “other jurisdictions”.

The real risk from the ignominious end of the endgame is that the world is bound to notice that the swing of the regulatory pendulum has changed direction. For more than a decade, US banks have benefited substantially from the fact that their capital was seen as more trustworthy than their global peers. They did not make as much use of internal modelling, they had more rigorous standards on loan losses, and lower levels of leverage.

Related:

PS9/24 – Implementation of the Basel 3.1 standards near-final part 2 (Bank of England)

Fed’s Relaxed Bank-Capital Plan Faces Bipartisan FDIC Pushback (Bloomberg)

At least three of five FDIC directors oppose the latest overhaul previewed by the Federal Reserve last week …

The central bank’s lead role in crafting the 450 pages of revisions was seen as one-sided by some FDIC directors, some of the people said. They privately described the recent round of negotiations with the Fed as lacking a meaningful opportunity for them to weigh in on specific changes contributing to the lower capital hike, according to the people.

Doesn’t matter. Banks + Fed + Democratic support > FDIC complaining they were sold out

A Failure Of Supervision

There are things worse than a bank supervision failure, such as our food supply. Read this and just substitute “the bank” for Boards Head” and “bank regulators” for USDA and you’ll see the same failures that were identified post SVB.

‘Imminent Threat’ Found at Boar’s Head Plant 2 Years Before Fatal Listeria Outbreak (NY Times)

Two years before a deadly listeria outbreak, U.S. inspectors warned that conditions at a Boar’s Head plant posed an “imminent threat” to public health, citing extensive rust, deli meats exposed to wet ceilings, green mold and holes in the walls.

But the U.S. Agriculture Department did not impose strict measures on the plant, in Jarratt, Va., which could have ranged from a warning letter to a suspension of operations.

Since then, other inspections found that many of the problems persisted, but again, the plant continued to process tons of beef and pork products, including liverwurst.

The agency later released reports dating to January 2022, which showed that a federal food safety assessment took place in September and October of 2022. During that review, records show, inspectors were already finding rust, mold, garbage and insects on the plant floors and walls.

Several food safety experts have said in interviews that the recurring instances of unsanitary conditions should have spurred stricter enforcement.

U.S.D.A. records show that if an investigator identifies an “imminent threat,” the agency “may take immediate action.” It remains unclear what prompted the review in September 2022.

Daniel Engeljohn, a former U.S.D.A. food safety policy official, said that the company’s production methods would have placed the Jarratt plant in the agency’s category of higher-risk food facilities. But the agency deems deli meat processing inherently risky, because people eat the meat without cooking it first, another step that can kill bacteria.

The records show that U.S.D.A. inspectors noted leaking pipes that dripped water onto the floor and condensation beaded along a 20-foot strip of ceiling above ready-to-eat food. They reported dozens of holes in the walls of the facility and “numerous” patches of green mold. They saw live beetles in the bathroom hallway. And they alerted plant workers to meat residue on food-contact surfaces.

In a room for packaging ready-to-eat hot dogs, investigators reported finding dirt, screws and trash on the floor. In the room where liverwurst was produced, rust covered portions of the walls and ceiling, paint was peeling off a wall and “product residue” was found on the floor.

Dr. Engeljohn said it would be typical for inspectors to move forward with strong enforcement if the problems could not be remediated promptly and if they observed unsanitary food production.

“There is just too much of a leaning toward letting the industry enforce itself, letting the companies get away with stuff that could easily be stopped,” said Ms. Entis

CFPB Uses The Death Penalty

Many of you may remember Sallie Mae; that’s now Navient.

Today, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) filed a proposed order against the student loan servicer Navient for its years of failures and lawbreaking. If entered by the court, the proposed order would permanently ban the company from servicing federal Direct Loans and would forbid the company from directly servicing or acquiring most loans under the Federal Family Education Loan Program .

The CFPB sued Navient for failing borrowers at every stage of repayment. The lawsuit alleges that Navient steered borrowers who may have qualified for income-driven repayment plans into forbearance instead. This practice was cheaper and simpler for Navient, but detrimental to borrowers.

…

In addition to its unlawful steering activities, the CFPB alleges Navient harmed student loan borrowers by:

Misleading borrowers about income-driven repayment plans …

Botching payment processing …

Harming the credit of disabled borrowers, including severely injured veterans …

Deceiving borrowers about Navient’s requirements for cosigner release …

Misleading borrowers about improving credit scores and the consequences of federal student loan rehabilitation …

Future Of Bank Supervision (2)

I wrote (rather positively) about Acting Comptroller Hsu’s speech on Evolving Bank Supervision. The Bank Policy Institute, has comments of their own in 4 Key Considerations on ‘Evolving Bank Supervision’

Risk-based Supervision & Horizontal Teams

They write that the focus on risk-based supervision is correct, but that:

Unfortunately, and as we have also described elsewhere, the risk-based approach to supervision that the Acting Comptroller describes is exactly contrary to the lived experience of bankers today, who frequently encounter an examination culture and practices that are increasingly focused on process rather than substance, and on immaterial matters rather than material financial risk.[4]

They focus on the potential downsides of “horizontal supervision”:

… horizontal supervision runs the risk of becoming a mechanism by which examiners review practices across a variety of banks, decide which one they prefer and then require the remainder to adopt what examiners have determined to be best practice, in ignorance of how one bank’s experience, capabilities and operations might differ from another. Such a process is problematic both because it effectively end-runs the open, public process by which new standards should be established, but also because it tends to create examiner-mandated monocultures across the banking industry, particularly in areas like information technology and risk management models and practices where “one-size-fits-all” prescriptions may be especially inappropriate and dangerous.

I have some, but not much, sympathy for their arguments. As to risk-based supervision:

In terms of planning, examination teams generally ruthlessly prioritize their resources, both in terms of number and skill. Never do they have enough staff to review everything, so they must prioritize.

When conveying findings, unless things have reverted since I left, examiners will lead their letters and annual results with the big issues. They are forced to decide what issues are Matters Requiring Immediate Attention, and those that are only Matters Requiring Attention. When there is a “get tough” moment, as happens following a notable failure, there can be pressure and a bias to rate more findings MRIAs. There should probably be a third category of Observations - this would give the Examiners-in-Charge even more latitude to classify what was found. When a weakness is found, it would be a failure to fail to inform management, but an MRA may still be burdensome.

I have less sympathy for their “horizontal” comments. It was not my experience that the process created a one-size-fits-all proscription, but rather that similarly risky institutions and activities needed to be held to the same standards. It was also true that examiners frequently took into account the business model, culture and practices of the individual banks, but frankly I’ve heard this card overplayed by bankers who did not want to acknowledge their shortcomings.

The one thing I would not is that, after the initial horizontal review of the major players, the standards would subsequently “bleed down” to the second tier players over time. This would usually be caused by the local examiners NOT coordinating with the experts and merely copying findings from other reports.

Asymmetry of Supervision

On the asymmetry of supervision (where headlines are made by bank failures, but supervision otherwise goes unacknowledged by the public), they write:

… asymmetry also means that bad supervision is just likely to go unnoticed as good supervision.

Supervision is ineffective not only in cases where supervisors miss issues and something goes publicly wrong; it’s also ineffective in cases where supervisors are focused on the wrong issues or immaterial matters, creating significant dead weight compliance burdens and a diversion of resources to immaterial matters and away from material ones. These negative consequences are frequently also invisible to the public because individual banks are barred from speaking of such instances with any specificity, and bank examiners generally have no incentives to be transparent about these kinds of supervisory failures.

This is probably true, but each of the agencies have processes to identify this over time. That doesn’t help in the moment, though.

D-SIBs

Lastly, they push back against his proposal to identify Domestic Systemically Important Banks, noting:

… the Federal Reserve and other U.S. banking agencies have established by rule a tiered framework that identifies four different categories of covered large banks and applies varying levels of enhanced prudential standards to each category.[11] Three of those categories encompass banks that are not global systemically important banks, which are identified through use of five indicators (i.e., size, cross-jurisdictional activity, weighted short-term wholesale funding, nonbank assets and off-balance-sheet exposure) that “provide a basis for assessing a banking organization’s [domestic] financial stability and safety and soundness risks.

… there is no question that such a framework already exists.

Have to fully agree with them here. There is no need for yet another set of tiering.

Regulation Often Has Unintended Effects

Forced to be active: Evidence from a regulation intervention

… we examine the impact of regulatory interventions by Scandinavian regulators. We compare the scrutinized Scandinavian funds with similar unaffected European funds. The findings suggest that the regulated Scandinavian funds preferred increased activity over fee reduction. Consequently, fund managers adopted more active management strategies, resulting in a significant 2% decrease in annual alpha. Therefore, the regulatory interventions resulted in unfavorable outcomes for investors.

ECB Supervision

Quote of the week, courtesy of Yale’s Steve Kelly.

How the ECB’s Ambitious Plan to Curb Risky Lending Veered Off Course (Bloomberg)

… banks were largely ignoring their guidance to curb lending to highly indebted companies, challenging the [ECB’s] authority. … Led by then-Chairman Andrea Enria, they agreed to enforce.

Banks, spooked by initial demands that they set aside billions in additional reserves, are criticizing everything from the methodologies and models to the use of outside consultants, who outnumbered ECB staffers more than ten to one. The ECB at one point even got into a debate over the proper collateral value of cows.

Supervisors at first took a closer look at what banks were doing in leveraged finance, imposing “capital add-ons” where the ECB believed risks were not fully captured by loan loss provisions. In 2023, three banks, including Deutsche Bank AG and BNP Paribas SA, had such surcharges.

Then, in September 2023, the crackdown intensified with work starting on a thematic review across 12 banks operating in the European Union that had large leveraged finance exposures, or where leveraged finance was a big part of the overall business.

The ECB and their consultants demanded granular data to populate as many as 100 data fields for a single debtor. … The information the ECB gathered was then fed into a “challenger model” where the watchdog generated its own probabilities for defaults and future losses.

When the initial results were delivered to banks in June, they called for an extra €13 billion ($14.4 billion) of provisions across the dozen lenders … The protests were fierce and prompted the ECB to delay the final results until September or October

The ECB is seeking to contain the fallout by telling banks it will weigh their feedback and has escalated the probe to Enria’s successor Claudia Buch. Officials have already more than halved their initial estimate of the extra provisions they want banks to make …

Stress Testing

Buffer Capital

Via BPI:

ICYMI in Research Exchange:

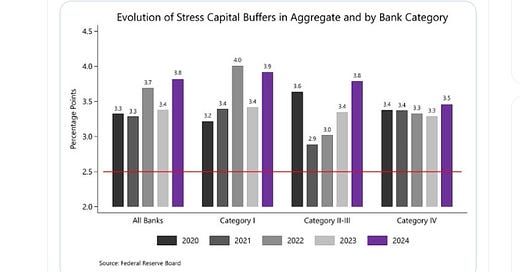

Based on the 2024 Federal Reserve stress test results, the aggregate of banks’ required capital buffers will increase 40 basis points, from 3.3 to 3.7 percentage points. 🧵 1/4

The increase varies by bank category, with Category I banks (or the GSIBs) projected to see the largest increase of around 50 basis points. 2/4

Category II-III banks are expected to see the next largest increase of around 40 basis points, while Category IV banks are looking at an increase of about 20 basis points. 3/4

The increase in SCBs is driven by greater capital depletion caused by reduced projected revenues and increased projected losses under this year’s severely adverse scenario. 4/4

Bowman on Stress Testing Requirements

The Future of Stress Testing and the Stress Capital Buffer Framework

As we conclude this most recent cycle of stress testing—and as many firms begin to turn to the next round—I think it is helpful to pause and consider whether and how the process could be improved. … drawbacks arguably make the process less fair, transparent, and useful than it could and should be.

While by no means a comprehensive list, I would like to address four of my concerns in particular:

volatility in firm results from year to year,

the challenge of linking stress testing outcomes with capital through the stress capital buffer,

the broad lack of transparency, and

the overlap with other capital requirements like the overlap between the global market shock in stress testing and the market risk rule under the Basel III endgame proposal.

Significant variability can disrupt these practices and require firms to hold more capital and higher capital management buffers than prudent business practices would indicate. … a more robust use of stress testing would require rationalizing the link between stress testing and capital to ensure that any change in overall calibration was driven by an intentional process that results in a reasonable policy outcome.

“Stability” should probably not be the goal. The nature of the stress test is state-dependent and that should be reflected in the anticipated stresses.

The link between stress testing and capital raises important policy questions about the optimal level of capital, but ultimately should not dissuade us from using stress testing to better understand firm-specific and broader financial stability risks. … In my view, an up-calibration of capital requirements through an expanded scenario-testing regime would not be supportable based on the underlying risks.

This last paragraph is key; she is trying to put light between capital levels and understanding financial stability risks. As readers know, I think that using the supervisory stress tests to set company-specific regulatory capital expectations is a practice that is not currently fit-for-purpose.

One persistent issue with the stress tests is the lack of public transparency around the models. This opacity frustrates bank capital management and allocation.

I am concerned about changes that could undermine the utility of both regulatory and internal stress testing at large firms. Regulators should not seek to take risk-management decisions away from banks. But greater transparency, debate, and discussion of test parameters need not lead to a dilution of standards.

Wise caution, but also not a move to eliminate the regulatory stress test requirements.

When we view capital requirements in their totality, one potential overlap can be found in the proposed changes to the market risk capital rules and operational risk rules with the "global market shock" and operational risk elements of the supervisory stress testing framework. We need to ensure that the risks captured and methodologies underpinning these distinct requirements do not lead to an over-calibration of capital requirements for activities that support the important role of U.S. capital markets in the global economy.

This is interesting from a theoretical point of view, and I am perhaps less sympathetic to the bank’s lobbying here. The global market shock represents a systemic event, whereby the operational risk charge represents an idiosyncratic shock. I’m sure firms would like to argue for diversification across these two, but if we are to use the stress test for regulatory capital I think the current practice may be the right one - although I may be missing something in the argument.

As we look ahead to the future of stress testing, I think we need to carefully consider how the current framework can be improved.

First, we need to address the excessive year-over-year volatility, which flows through to the calculation of stress capital buffers. As I noted, capital planning for many firms is a long-term enterprise, and excessive volatility and unpredictability of stress capital buffer levels can increase costs and complicate capital allocation and management.

I would eliminate the stress test requirement, but if it remains it should stay state-dependent. Regulators could use the counter-cyclical buffer if they wanted to provide relief.

… we should adjust the compliance framework for stress capital buffers. Firms should not be forced to comply with higher capital requirements after only a few months' notice but should have a reasonable time frame for compliance. I would note that a longer compliance runway is particularly important in a world in which testing is opaque and volatility continues to be excessive.

Interesting proposal here - would like to see this fleshed out further.

Finally, as we move forward with Basel III implementation, we need to take a careful look at whether market risk and operational risk requirements are overlapping and redundant with the "global market shock" and operational risk elements of stress testing and think about the calibration of these requirements in the aggregate. Would these tests in tandem produce excessively calibrated capital requirements, and if so, what would the impact be on U.S. capital markets? In my view, there are strong indications that as currently formulated, the combination of these requirements would result in an excessive calibration of risk-weighted assets for market making and trading activities. And of course, we must think broadly about the optimal level of capital in the banking system, taking into account the full range of risk-based and leverage capital requirements and long-term debt requirements.

This is lobbying for lower requirements for the biggest trading banks. But as they are the source of the systemic risk in the system (and not the SVBs of the world) I would not start down the slippery slope of capital requirement reductions. To the extent that the requirements force these banks to shrink, and allow the rise of other players, this is a financial stability enhancing outcome. Capital incentives matter.