Perspective on Risk - May 10, 2024

SLOOS; Reciprocal Deposits; CRE; Private Credit; Remediating Liquidity Risk of NBFIs; The FDIC’s Culture Is Broken; Satisfaction; Brian's Perfect Job

I really want to write on A.I. and climate and some other topics, but the banking stuff keeps getting in the way, and I haven’t yet even tried to address the FDIC compensation proposals.

The State Of The SLOOS

The Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, or SLOOS, is a highly followed indicator. It provides a wealth of data, but this can be noise or signal. Let’s review.

The first thing to note is that the SLOOS provides information on two related, but different, aspects: lending standards, and loan terms.

Let’s review some literature that show where the SLOOS data has predictive value, starting with two from one of my favorite former colleagues, Don Morgan.

We will start with Listening to Loan Officers: The Impact of Commercial Credit Standards on Lending and Output (Lown, Morgan & Rohatgi, 2000) which derives a

Statistical analysis reveals a strong correlation between loan officers’ reports of tighter credit standards and slowdowns in commercial lending and output.

Reported changes in credit standards can also help predict narrower measures of business activity, including inventory investment and industrial production.

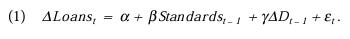

We estimate a loan growth equation of the following form:

The dependent variable is growth in commercial and industrial loans at U.S.-chartered banks over quarter t, expressed at an annual percentage rate. Standardst-1 is the net percentage of loan officers reporting tightening standards for approving commercial loans to large and medium-sized firms.

Lown and Morgan expand on their 2000 paper in The Credit Cycle and the Business Cycle: New Findings Using the Loan Officer Opinion Survey (NY Fed’s Morgan & Lown, 2006)

Fluctuations in commercial credit standards are highly significant in predicting commercial bank loans, real GDP, and inventory investment in the trade sector. … Credit standards are far more informative about future lending than are loan rates …

Shocks to the federal funds rate do not cause changes in standards…

We found a negative relationship between banks’ capital ratios and their lending via standards but that link between bank capital and lending standards was statistically weak.

Morgan and Sporn also wrote Getting More from the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey? (2017)

Although it may not be obvious at first glance, lending standards and growth in loans and output are negatively correlated. That negative relationship is starkest during the financial crisis and Great Recession, and also over the 2001 recession.

… lending standards and loan terms sometimes do move independently, and occasionally even in opposite directions

Adding loan terms to their model of forward loan and GDP growth enhances the model, but only marginally.

Adding loan terms to the model reduces the average forecast error (root mean squared error) for loan growth by 6 percent (from 0.97 to 0.91) and reduces the root mean squared error for GDP growth by about 9 percent (from 2.09 to 1.90).

Morgan goes on to cite several additional papers that I have linked in the footnotes.1 Basset, et. al. provide additional support for these hypothesis, and Bernanke, et. al. in describing the importance of the credit channel.

So what we know is that changes to standards has a several quarter effect on both loan growth and GDP growth, and that changes to loan terms have a much smaller effect, and that changes to standards are more important than changes to the fed funds rate.

So let’s look at the SLOOS data on standards.

The first observation is that standards on C&I loans are highly, positively correlated regardless of whether to large or small firms. The second observation is that the correlation between standards for C&I loans and consumer installment loans are negatively correlated.2

Next, since there is bias in the data (all three series have positive means for tightening), we need to normalize. In the top graph, I normalize for just the mean and standard deviation of the large C&I tightening series. In the second graph, I normalize for all four statistics through a log transformation. I’ve marked formally declared recessions with gray bars.

We have had eight quarters of tightening. The GFC was preceded by about 14 quarters of net loosening, not tightening. Going back to 2000, the recession was preceded by 6 quarters of moderate tightening, which was preceded by a long period (19-19 quarters) of continuous loosening.

So if I had to summarize my views here, I’m not particularly concerned about the tightness of credit standards. The bank balance sheet channel should play a stronger role (ala Bernanke), and as long as the balance sheets are not materially impaired by the developing CRE losses, the credit channel should be fine.

Reciprocal Deposits

Jason Cave writes a nice, direct piece for Bank Director magazine titled Using Reciprocals To Maintain Deposit Stability. I didn’t think much about small bank liquidity in my time at the Fed, given the portfolio of risks I looked at, but Jason did in his role at the FDIC. I want to highlight this article for two reasons: first, how small banks can modify their liquidity run risk, and second because it points to a WSJ article The FDIC Should Act Like a Real Insurer.

Community Bank Liquidity

How well a [community] bank does at holding onto those [local community] relationships can spell the difference between value creation and destruction, and also impact its acquisition and growth prospects.

Herein lies a challenge: While banks might view local business accounts as core, regulators can consider them “volatile” if they are too large. … If an examiner believes a bank has too much of its deposit base in these volatile funds, it could be required to raise more capital, increase liquidity or even take more extreme action to reduce reliance on a specific business client.

Fortunately, there’s a solution that can allow banks to maintain deposit stability and those valuable relationships. Reciprocal deposit programs are designed to spread the concentration risk of large depositors across a wide swath of banks, providing participants with stable core deposits.

The FRB Dallas wrote a nice writeup3 on how these programs operate to allow depositors to keep their large deposits fully insured.

This type of program is useful in that it changes the risk profile of the deposits from a strictly local, idiosyncratic run problem to a broader depositor base perhaps spread over different geographic and industry markets.

The FDIC Should Act Like a Real Insurer

In his piece, Jason writes:

In a recent opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal, “The FDIC Should Act Like a Real Insurer,” former acting Comptroller of the Currency Brian Brooks challenged conventional regulatory wisdom by proposing that the FDIC charge higher premiums for banks that hold high uninsured deposit balances unless they use reciprocal deposit arrangements to lower their risk.

In the article, Brooks writes:

The FDIC should encourage—or require—banks to spread the amount of money they hold in excess of insurance limits among other institutions.

The FDIC knows when depositors and banks could benefit from spreading funds in a reciprocal deposit arrangement. It could encourage banks to use these practices by setting a threshold of uninsured deposits over which institutions would have to pay higher premiums unless they use reciprocal deposit arrangements to lower their risk. If the FDIC wanted to take a sterner hand, it could build reciprocal deposit arrangements into its supervisory expectations for risk management. Banks that failed to use the available tools for reducing uninsured deposits would face enforcement actions.

I’ll admit, it’s a bold and interesting proposal that’s worth investigating. I’m not sure it works for large firms with payroll obligations, etc. This could force further disintermediation of the banking system, but it is the kind of interesting thinking that should be encouraged.

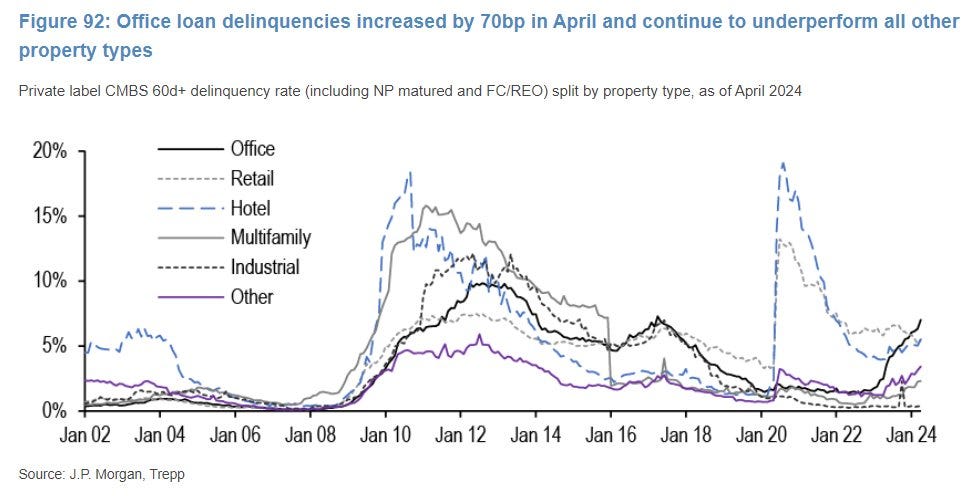

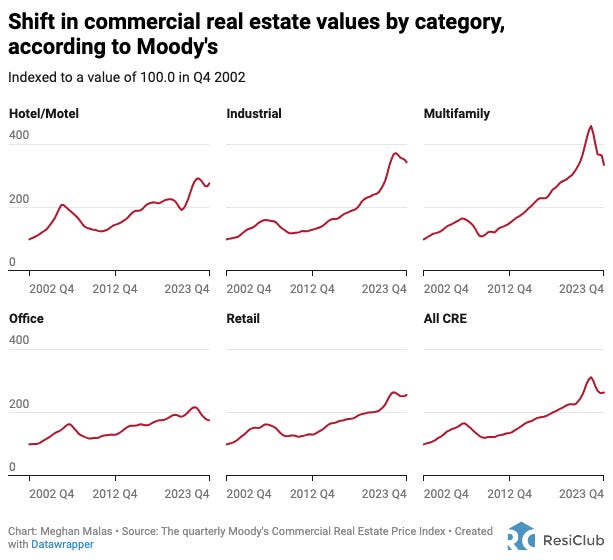

More CRE

Office Continues To Deteriorate

Watch Multifamily

More Private Credit

Systemic Risk & NBFIs

Stijn Claessens writes an article on Vox Non-bank financial intermediation: Research, policy, and data challenges that discusses his paywalled ($6) paper DP18945 Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Stock Take of Research, Policy and Data (Claussen). Claessens is widely followed by regulators globally.

This column reviews research and policy work on this form of financial intermediation from a financial stability perspective.

… since the GFC [NBFI] growth has exceeded that of other financial assets.

NBFI assets now account for nearly one-half of total global financial assets.

In 2022, approximately 65% was held by so-called other financial intermediaries (OFIs) – institutions other than central banks, banks, public financial institutions, insurance corporations, pension funds, or financial auxiliaries. Among OFIs, about three-quarters are collective investment vehicles (CIVs), such as money market funds (MMFs), fixed-income funds, balanced funds, hedge funds, and real estate investment trusts.

The risk-reduction benefits of NBFI arise in large part from the diverse forms of financial services it provides.

NBFI generally uses instruments that involve greater risk-sharing among a wider pool, which can benefit borrowers.

Also, since NBFIs do not have very highly levered balance sheets and are not core to the payment system as banks are, individual NBFI failures tend to have less systemic consequences. Evidence also supports that better-developed capital markets, typically associated with more NBFI, mitigate the negative real effects of crises.

But NBFI comes with its own risks, related specifically to interconnections and interactions between liquidity and leverage, and can be procyclical too.

The connections between NBFIs and banks … are much smaller today due to various reforms.

The main systemic risk analysed in relation to NBFI recently has been its fragile liquidity. The underlying mechanisms are well-known (Aramonte et al. 2023) and were present in several recent stress events. … Fragile liquidity can arise from those NBFIs that issue liabilities with near-money characteristics yet are backed by illiquid assets and channelled through vehicles with no (or limited) ability to generate their own liquidity. These forms include MMFs and other types of CIVs.

The Alphaville team, in contrast, dug up a paper, Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin, by Acharya, Cetorelli and Tuckman that argues

… that NBFI and bank businesses and risks are so interwoven that they are better described as having transformed over time rather than as having migrated from banks to NBFIs.

In The increasingly blurred lines between banks and NBFIs, the Alphaville crew write:

The whole point of the post-GFC reforms was, in the words of the authors, “to strengthen the banking system and protect it from the failures of NBFIs”.

But using this and other data, they argue:

post-GFC reforms have encouraged transformations that split intermediation activities across NBFIs and banks so as, in fact, to make the sectors more interdependent. As a result, the systemic risk of the two sectors is more highly correlated after than before the GFC.

Using new(ish) and enhanced financial accounts data for the United States, they find that — rather than NBFIs substituting for bank business — NBFI and bank businesses and risks are better seen as increasingly interwoven.

Having read the paper, I’m not convinced there is much new here. Banks offer products that are complementary to non-bank origination, such as warehouse lines.

I’m wondering, since we converted all of the old investment banks to regulated banks, this whole private credit thing is just recreating past intermediation, albeit with a twist.

Fed Gov. Cook Chimes In

Gov. Cook spoke at Brookings: Current Assessment of Financial Stability

Overall, I think that the growth of private credit likely has not materially adversely affected the financial system's resilience.

In the U.S., private credit funds' assets under management have grown rapidly in recent years. They were estimated to stand at $1.1 trillion as of September 2023, comparable in size to both the high-yield bond and institutional leveraged-loan markets.

Private credit funds appear well positioned to hold the riskiest parts of corporate lending. These intermediaries generally use little leverage and are organized as closed-end funds, which means that investors cannot withdraw the funding supporting the investments.

More Bloomberg Chatter About Private Credit

Private Credit Stress Brings Anxiety, Opportunity to Milken (Bloomberg)

Private credit managers are bracing for an uptick in stress across corporate America as higher interest rates for longer mean some companies will struggle with their debt loads.

… some expressed concern that liquidity issues for borrowers that binged on debt when rates were low are being masked by amendments to loan terms, such as maturity extensions and payment-in-kind arrangements.

Sponsors are prepared to wait until they can earn their way back to higher valuations before exiting company investments, and are finding willing partners in private credit to help, said Jeffrey Solomon, president at TD Cowen.

Private Equity Scrambles to Find an Alternative to IPOs to Unlock $3 Trillion (Bloomberg)

A return to true health in the IPO pipeline could take until next year, and a record $3.2 trillion was tied up in aging, closely held companies at the end of 2023, Preqin data found.

Behind the scenes, the private equity shops saddled with bulging portfolios … are still scrambling to come up with alternative exit strategies.

Blackstone Taps Vast Source of Cash in $1 Trillion Credit Push (Bloomberg)

I wonder if Bloomberg read the last PoR?

After sealing a partnership with Resolution — similar to deals with arms of the giant insurers American International Group and Allstate — Blackstone is now a key asset manager for the firm, in charge of a cash pot that could hit $60 billion.

Remediating The Aforementioned Liquidity Risk

Money Funds Start Shuffling Assets Ahead of SEC Rule Changes

Funds are starting to shift their holdings in the $6 trillion US money market ahead of a spate of new rules that will likely boost demand for government securities at the expense of riskier assets.

As of mid-April, about five of these [institutional prime money market] funds — including the two largest — had announced plans to convert to government-only holdings or close altogether to avoid Securities and Exchange Commission measures that take effect later this year.

There’s about $650 billion parked at institutional prime funds, with about $605 billion concentrated in 20 entities, Barclays estimates.

… institutional prime funds only make up 45% of the prime money-market space — versus more than 70% in 2016.

The FDIC’s Culture Is Broken

The Cleary Gottlieb independent review of allegations of sexual harassment and interpersonal misconduct at the FDIC is devastating. No way around it.

We have completed our review, and find that, for far too many employees and for far too long, the FDIC has failed to provide a workplace safe from sexual harassment, discrimination, and other interpersonal misconduct. We also find that a patriarchal, insular, and risk-averse culture has contributed to the conditions that allowed for this workplace misconduct to occur and persist, and that a widespread fear of retaliation, as well as a lack of clarity and credibility around internal reporting channels, has led to an underreporting of workplace misconduct over the years.

We considered whether the current culture of the FDIC—as reported and experienced by its employees—embodies these values. As set forth below, the experience of many FDIC employees is that it currently does not.

Select quotes won’t do this justice. It must be read. Maybe I’ll just lay out the major findings of the root cause analysis:

Lack of Accountability: Actual and perceived lack of accountability for workplace misconduct that has led to negative consequences to culture and reporting of issues.

Fear of Retaliation: Widespread fear of retaliation that has prevented employees from raising and reporting issues.

Insufficient Prioritization of Workplace Culture: Lack of sufficient and sustained prioritization and commitment to workplace culture issues over the years.

Patriarchal, Hierarchic, and Insular Culture: A culture described as “patriarchal,” “hierarchic,” and “insular” with outdated notions of appropriate workplace behavior and interpersonal workplace interactions.

Risk Aversion: Risk averse culture that has contributed to both actual and perceived lack of accountability.

Lack of Clear Guidance: Lack of clear guidance on proper workplace behavior and how to address improper workplace behavior.

Abuse of Power Dynamics: Abuse of certain power dynamics and imbalances within the FDIC has contributed to conditions that foster workplace misconduct.

Confusing and Ineffective Reporting Channels: Confusion as to proper reporting channels and processes involved that has contributed to underreporting.

Investigative Processes Lack Credibility: Current investigative functions that lack credibility among employees and are viewed as being protective of management.

Insufficient Recordkeeping: Lack of proper recordkeeping that would allow the FDIC to understand and keep track of the volume, trends, and other information relating to workplace conduct.

I highly doubt that this can be fixed internally. Perhaps it’s time to merge the FDIC with the OCC. Again, I can’t say strongly enough how bad this is. Chair Gruenberg must go.

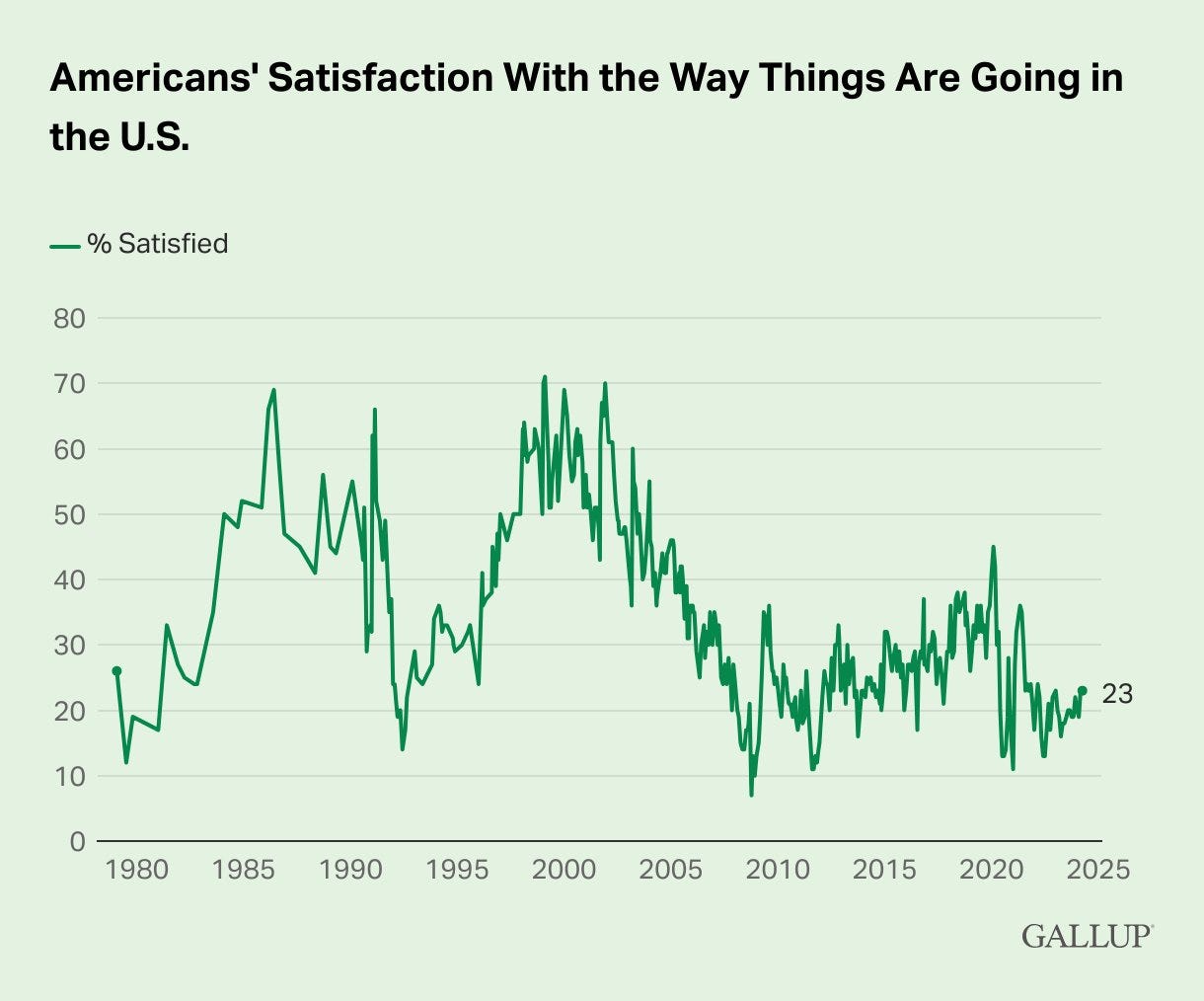

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction

Maybe it’s a Y2K hangover, or 9/11, or the GFC, or polarization …

I Found My Ideal Job (Highest & Best Use)

Changes in Bank Lending Standards and the Macroeconomy (Fed Board’s Bassett, Chosak, Driscoll, and Zakrajsek, 2012)

Using bank-level responses to the Federal Reserve’s quarterly Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey, this paper develops a new measure of movements in the effective supply of bank-intermediated credit. The indicator of shifts in the supply of bank loans to businesses and households corresponds to changes in lending standards that—using an econometric model—have been adjusted for the bank-specific and macroeconomic factors that, in addition to affecting banks’ credit policies, can also have a simultaneous effect on the demand for credit.

Inside the Black Box: The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission (Bernanke and Gertler)

I’m using data from 1990Q2 through 2024Q2, which is the period where the three series all have data.