Perspective on Risk - July 17, 2025 (Banking & Regulation)

The value of independence; Rating management; On MRAs; Repo standards; Some Papers

This post is a back-to-basics. No big picture thoughts. Very little funky stablecoin musings.

The Value of Fed Independence

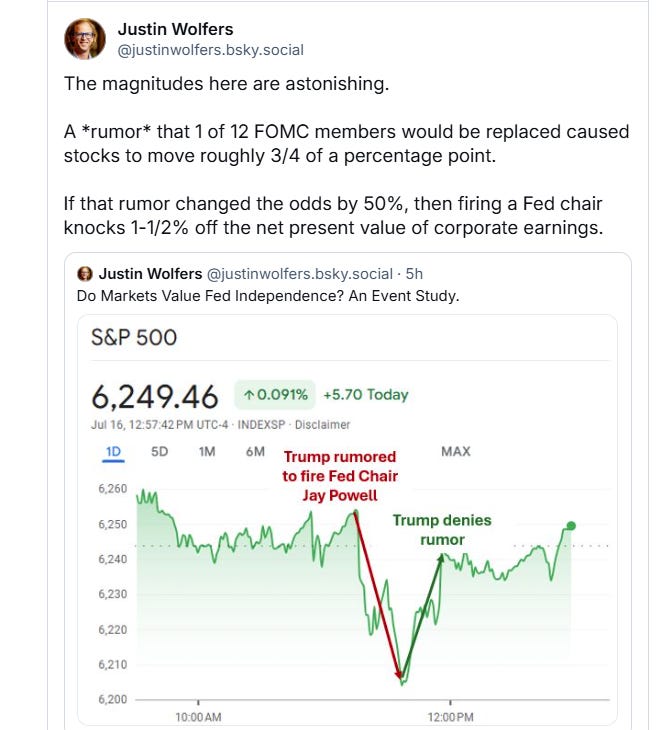

Trump conducted a nice natural experiment when he leaked that he was going to fire Fed Chair Jay Powell. Justin Wolfers summarizes the results pretty clearly:

The market cap of the S&P 500 is about $50 trillion, so today's adventure wiped off about $250 billion in minutes, only to restore that sum when Trump denied the rumor.

I thought it would be higher.

Rating Management

One of the best things that examiner CAN do is judge how well firms have established processes for managing risk. This includes things like management’s attention, Board awareness, automation, audit coverage, etc. They see a wide variety of firms and can readily peer-benchmark firms (frankly, this was one motivation behind the construct of ‘horizontal exams’). This is what is being referred to as ‘management.’

The Fed is proposing changes to how they rate large banking organizations, and in particular the ‘management’ aspects.

Specifically,

The proposal would revise the Frameworks such that a firm with at least two Broadly Meets Expectations or Conditionally Meets Expectations component ratings and no more than one Deficient-1 component rating would be “well managed.”

A firm would not be “well managed” if it receives a Deficient-2 for any of the component ratings, consistent with the current Frameworks.

The proposal would also remove the presumption in the Frameworks that the Board will bring an informal or formal enforcement action on firms with one or more Deficient-1 ratings. Instead, decisions to issue enforcement actions to those firms would be made based on the particular facts and circumstances of the firm. The Frameworks would continue to contain a presumption of an enforcement action for a firm that receives a Deficient-2 rating for any component

Background

The current LFI rating system has three components:

capital planning and positions;

liquidity risk management and positions; and

governance and controls.

Each component is rated based on a four-point non-numeric scale:

Broadly Meets Expectations,

Conditionally Meets Expectations,

Deficient-1, and

Deficient-2.

I had left by the time they created this system, which frankly I felt was a step back from the RFI system (which full disclosure I helped develop). The RFI system cleanly separated the management or risk (the R component) from the financial condition (F component) of the firm under the premise that one could have strong financial performance, but weak controls, and visa versa.1 In the current framework, it is less than clear where would account for, say, weaknesses in Treasury risk management practices.

Nevertheless, the current system is the one in place and that’s proposing to be changed. Let’s evaluate the proposed changes.

Rules-Based Triggers vs. Discretionary Judgment

The current system operates with a clear, codified rule: a single "Deficient-1" rating automatically results in a firm being deemed not "well managed". This status, in turn, triggers a presumption of an enforcement action. The process is largely automatic once the initial rating is assigned.

The proposal systematically replaces these automatic triggers with discretionary decision points for supervisors. The link between a single "Deficient-1" rating and a "not well managed" status is severed. Crucially, the presumption of an enforcement action for one or more "Deficient-1" ratings is removed. Instead, the decision will be made "depending on the particular facts and circumstances of the firm.”

If properly implemented, this is a step back towards “supervision” and away from “enforcement” so I support.

"Weakest Link" Determination vs. Holistic Assessment

The documents explicitly state that the current approach determines a firm's "well managed" status "based solely on any one of its component ratings.” Well that’s just pretty harsh if true.

The proposal mandates a more comprehensive and balanced view. It requires supervisors to consider the "totality of the component ratings" when determining the "well managed" status.

This is a return to the old school ways. his shift allows for a more proportional and risk-sensitive assessment. A firm with two strong components (e.g., Capital and Liquidity) can be recognized for its overall resilience, even while being required to address a specific deficiency in Governance and Controls. It better reflects the reality that a firm can have a discrete, solvable problem without posing a systemic threat.

Recalibration of Incentives

Firms

The primary incentive for firms is to avoid a "Deficient-1" rating in any single category, as the consequences are severe, automatic, and public. This can lead to a highly tactical, compliance-focused approach aimed at preventing a specific rating outcome.

This recalibration shifts the incentive from merely avoiding a single negative trigger to demonstrating broad, holistic financial and operational strength. It encourages firms to manage their overall risk profile effectively, with the understanding that while a single issue won't automatically lead to the harshest consequences, it will still require prompt and effective remediation to avoid further action.

The Board acknowledges that a bank may be marginally less incentivized to immediately address issues underlying a single Deficient-1 component rating.”

Examiners

The proposal affects the incentives for examiners by shifting their role from the application of a rigid rule to the exercise of comprehensive, risk-based judgment. While the proposal does not change the underlying standards for assessing a firm's capital, liquidity, or governance, it alters the consequences of those assessments. This, in turn, recalibrates the professional incentives for the examiners conducting the review. The proposal, however, requires a more holistic assessment to determine the "well managed" status. An examiner is now incentivized to understand the context of a single deficiency. They must determine if it is an "idiosyncratic deficiency" in an otherwise strong firm or if it is indicative of a broader institutional weakness.

The proposal removes the "presumption" that a firm with one or more "Deficient-1" ratings will be subject to an enforcement action. This changes the examiner's role. Instead of applying a rule (i.e., a "Deficient-1" rating leads to a presumed enforcement action), the examiner must now exercise judgment. They are incentivized to build a well-reasoned case, based on the "particular facts and circumstances" of the firm, to justify why an enforcement action is or is not necessary. This likely requires more more robust analytical argument to support their recommendation.

Conclusion

I hadn’t expected to like this proposal when I first heard about it. I thought it would be another cave to the industry, a weakening of post-GFC reforms. But after thorough review, and of course the proof of the pudding is in its tasting, this is a big step back to letting supervisors be supervisors, and not compliance officers or auditors. Judgment, particularly of management and the efficacy of risk management practices, is the critical skill that you should expect from an examiner, and a good examiner can be quite effective at doing this. The financial part is easy, and frankly should just be automated anyway.

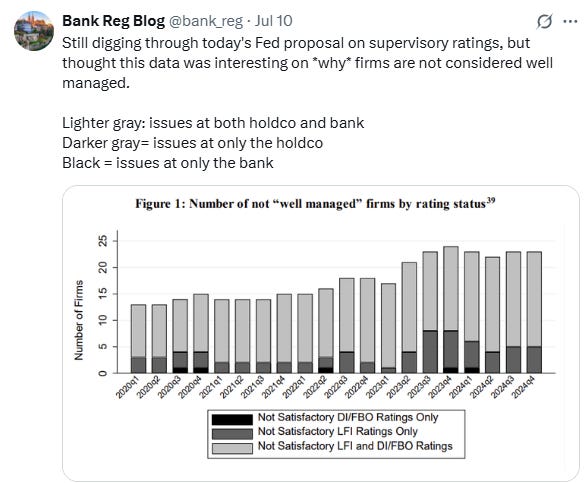

Fed. Gov. Cook issued a statement that summarizes thusly:

I am concerned by the fact that a majority of banking organizations subject to the LFI framework, which applies to the largest banking organizations, do not qualify as "well managed."

Such unsatisfactory ratings could reflect that significant deficiencies identified by supervisors are not being remediated with appropriate speed. However, certain design features of the LFI framework, which was finalized in 2018, may have contributed to these results.

Today's proposal would mitigate the consequences of a single "deficient-1" rating for banking organizations, which may be appropriate when such a single rating would not provide an accurate view of the overall condition of the organization. However, in my view, a potentially better, more comprehensive approach—as raised in question 5 of the preamble—would be to add a composite score to the LFI framework. A composite score would produce a more holistic assessment of the organization—across individual components—and allow more nuance to distinguish well-managed from not well-managed organizations.

Matters Requiring Attention

Here are two articles that present sharply contrasting perspectives on Matters Requiring Attention (MRAs) in bank supervision.

Understanding MRAs (UponFurtherAnalysis)

The 3 Letters at the Heart of Bank Supervision Dysfunction (BPI)

The BPI argues against MRAs on legal and effectiveness grounds. BPI's position is that MRAs operate as mandatory commands without proper legal authority. They argue that:

MRAs were "invented by agencies through guidance documents issued without notice and comment"

Examination authority only permits reviewing books/records, not commanding specific actions

Enforcement authority requires due process (notice and hearing), which MRAs lack

MRAs are "nowhere mentioned in law or regulation" and banks face "criminal sanction" for disclosing them

Further:

MRAs "often fail to identify any particular practice of concern" and "seek to direct how banks manage themselves at an operational level, emphasizing process over results." Using SVB's 31 outstanding MRAs as evidence of supervisory dysfunction, they argues supervisors were distracted by process issues instead of focusing on material financial risks.

On the other hand, UponFurtherAnalysis sees MRAs as a “legitimate supervisory tool.” It asserts that SVB's liquidity-related MRAs were "spot on" - noting deficiencies in stress testing assumptions, contingency funding plans, and liquidity limits that directly predicted the bank's failure. They further point out that First Republic had only 2 open MRBAs but still failed, undermining the "too many MRAs" argument. Lastly, the former examiner emphasizes that "inadequate processes mean that the bank and its regulators lack a reliable way to even measure the risk, much less control it"

My 2 cents:

The BPI’s arguments are weak sauce.

I was present when MRAs and MRIAs were first mandated. I did not particularly like them because they put the responsibility for prioritizing risk management fixes in the hands of the regulators rather than the bankers. Over time I came to like them even less as nearly every supervisory “finding” had to be coded as either an MRA or an MRIA. Heaven forbid an examiner from finding something and NOT writing an MRA. I think it harmed the constructive dialogue between the bankers and the supervisors. But I was in the minority with that view.

Now, the flip side is that in the pre-MRA/MRIA days, we frequently had to force examiners to prioritize their findings, something they often found difficult to do. And I remember times when we would discuss whether something was important enough to make the written report, or was it something that could just be handled through a conversation with bank management. With MRAs/MRIAs at least one could readily tell what they viewed as most important.

Repo Standards

One of the lesser known, but most important, industry groups in finance is the Treasury Market Practices Group.

You may recall that in February the TMPG issued for consultation "Non-Centrally Cleared Bilateral Repo and Indirect Clearing in US Treasury Market: Focus on Margining Practices." The February white paper essentially identified that the NCCBR segment had devolved into a "race to the bottom" where competitive pressures were driving firms to accept uncompensated credit risk through zero haircuts, creating a systemic vulnerability that was largely invisible to regulators and market participants due to the bilateral and opaque nature of these transactions.

After consultation, the TPMG has now released Recommended Best Practices for Treasury Repo Risk Management.

The final standards establish that

all UST repo should be prudently risk managed. This includes the application of haircuts (or margin) on the value of the securities, in concert with other risk management techniques.

The May standards, however, show more flexibility than the Feb. white paper by allowing

haircuts (or margin) can be applied together with other risk management tools, such as position limits, netting agreements, and/or portfolio margining, and should be supported by a robust risk management framework.

The May standards require robust documentation and frameworks that make risk management practices more transparent. The accompanying Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Treasury Repurchase Agreement Risk Management provides additional guidance to ensure consistent interpretation and implementation.

To me, this is financial supervision (writ large) at its best, even though it is not formally done by bank supervisors! What was a “race to the bottom” through coordination (and suasion) leads to a positive externality that leaves the system competitive, but in a safer place. Now it is up to firms to implement the standards, and supervisors to hold firms accountable for meeting the standards.

For what its worth, the issues here are echoed in the BIS’s Annual Economic Report June 2022.

… the post-GFC landscape has government bond markets at its centre and asset managers of various stripes as the key intermediaries. As a result, a key risk today is liquidity stresses in government bond markets. Hedge funds, in particular, have become key providers of procyclical liquidity in government bond markets, often employing highly leveraged relative value trading strategies. By using government securities as collateral in the repo market to borrow cash for additional securities, these strategies boost returns but are also vulnerable to adverse shocks in funding, cash or derivatives markets. This vulnerability has increased further as financing terms have become increasingly lax. Haircuts have gone to zero or even negative in large sections of the repo market, meaning that creditors have stopped imposing any meaningful restraint on hedge fund leverage. This higher leverage leaves the broader market more vulnerable to disruptions, as even slight increases in haircuts can trigger forced selling and amplify financial instability. Such adverse dynamics were on display, for example, during the market turmoil of March 2020, and contributed to the volatility spike in Treasury markets in early April 2025.

Some Financial Stability Papers of Interest

Financial Crises

Gary Gorton is out with a new paper, Why Financial Crises Recur, arguing that lawmakers repeatedly make two mistakes

First, lawmakers fail to understand that “banks”—both traditional banks and shadow banks—produce runnable short-term debt, unlike other firms in the economy. To produce short-term debt, banks operate with opacity. Yet a regulatory framework based on secrecy is diametrically opposed to our dominant market-based paradigm that values transparency above all else.

Second, lawmakers fail to understand the difference between a “systemic crisis” and the failure of individual banks. Aiming to enhance the safety and soundness of individual banks is not sufficient to produce system-wide stability.

Committing these two errors, he argues, leads to systemic risk and a recurrence of crises.

The first point is about money (or collateral) substitution. The goal is to create “near-money” that trades at par (think super-senior CDOs in the GFC, or maybe stablecoins today). In economists-speak, he argues that “money” needs to be “information-insensitive” AND no one should have incentive to gather this information (!). Those of you familiar with my favorite paper, Corrigan’s Are Bank’s Special? will read the subtlety in this line:

Producers of that runnable short-term debt—whether traditional commercial banks or shadow banks like money market funds and stablecoin issuers—are special, and they require more opacity than Congress and regulators typically propose. … Transparency is of paramount importance, as sunlight is often considered to be the best disinfectant. But the opposite is true for producers of runnable short-term debt, particularly during a panic.

He is arguing that MMF and stablecoin issuers maybe should be considered “special” in the Corrigan meaning of the term.

The second point is about understanding the financial system, and not just relying on making an individual institution bullet-proof (macro-prudential vs micro-prudential regulation)

He argues that these mistakes are being made again with the GENIUS Act and stablecoins. He writes in an article for Harvard Law School Forum:

In short, attempts to regulate stablecoins, like the GENIUS Act, may be able to guard against idiosyncratic risk, but it cannot prevent systemic risk.

Financial System Structure

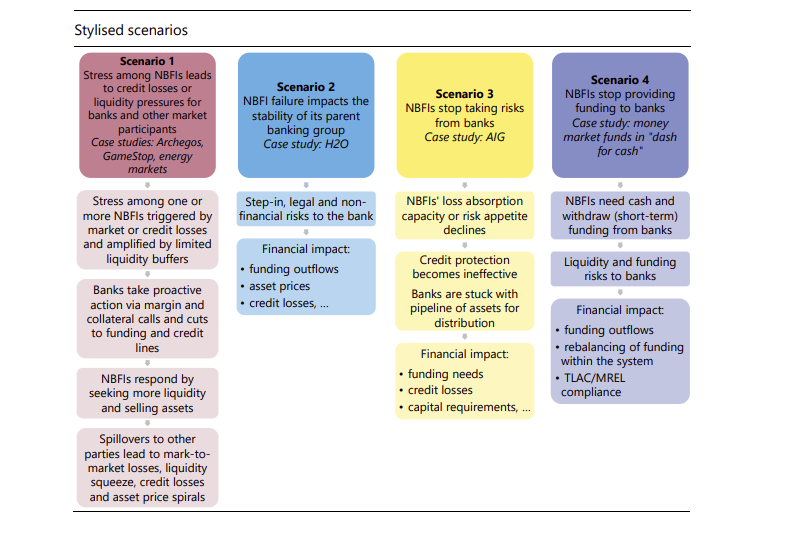

Earlier, I highlighted a section from the BIS’s Annual Report that discusses non-bank Treasury intermediation in the context of the repo market. In July, the BIS published Banks' interconnections with non-bank financial intermediaries that “investigates banks’ interconnections with non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) and aims to set out plausible stress scenarios that could impact the safety and soundness of banks.”

The paper proposes that while the G-SIB banks are much better capitalized than in the GFC,

their central role in providing services to NBFIs may make the system vulnerable to procyclical reactions during market stress. If G-SIBs are less willing or able than other market participants to take on certain risks (especially if they reduce their activities during shocks to protect themselves from risk), then their relative rigidity could hinder the ability of the system to withstand shocks.

The paper considers three stylized scenarios:

If you remember, I outlined a non-bank led financial stress scenario involving Blackstone, Blackrock and Jane Street in the Perspective on Risk - July 8. 2025. My scenario would align with BIS scenario 4, but I perhaps went a bot further by showing the speed of contagion, demonstrating multi-node failure and illustrating how market structure (ETF arbitrage, repo funding) amplifies the BIS's theoretical channels.

Liquidity Risk

The Rise in Deposit Flightiness and Its Implications for Financial Stability (Liberty Street) discusses deposit segmentation, sensitivity and changes in deposit composition following Covid. Some solid fundamental work.

… we estimate how much deposit flows into a bank change when the bank raises its deposit rate by 1 percentage point. … Depositors’ flow sensitivity increased following the 2008 financial crisis, declined in the mid-2010s, but rose sharply after the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. By early 2022, deposit flow sensitivity had reached record highs, meaning deposits were more likely than ever to respond to changes in interest rates just before the Federal Reserve began its rate hiking cycle.

We show that at any given time, the investors who choose to hold bank deposits are less sensitive to interest rates than those who opt for alternative investments, such as money market funds. We further show that, when deposits flow into the banking system, they tend to be more rate-sensitive than the existing depositor base, making the overall deposit base more flighty.

… deposits from nonfinancial corporations grew significantly more than retail deposits as reserves expanded from early 2018 to late 2021. These corporate deposits, which tend to be more volatile than retail deposits, subsequently declined at a faster rate once reserve balances started to shrink and interest rates began rising in 2022. The disproportionate growth and subsequent decline of corporate (as well as the highly volatile NBFI) deposits support the idea that changes in deposit composition over time play a crucial role in driving the dynamics of aggregate deposit flightiness.

OCC’s Perspective on Risk

OCC Report Highlights Key Risks in Federal Banking System (OCC)

I generally find the interest in these reports is to track the delta from the previous report, which in this case was a December 2024 report reflecting the fall of that year.

The most substantive change is in commercial credit risk.

Dec. 2024: Commercial credit risk remains moderate and shows signs of stabilizing as risks are better identified, monitored, and controlled.

June 2025: Commercial credit risk is increasing, driven by growing geopolitical risk, sustained higher interest rates, growing caution among businesses and their customers, and other macroeconomic uncertainty.

They seem more sanguine about multi-family CRE:

Dec. 2024: Multifamily risks "remain elevated, particularly in the luxury segment"

June 2025: Multifamily market "is projected to stabilize later this year and the industrial market is expected to stabilize within the next 12 to 18 months"

In general, there is more optimism about bank performance and market conditions with nuanced improvement in some areas (NIMs, multifamily CRE outlook).

Thiel Risk

Balls on this guy.

I stood for “impact” of the non-bank subsidiaries on the bank and is irrelevant for this discussion.