Perspective on Risk - July 11, 2025 (Demographics)

The American Demographic Anomaly Comes to an End; A Hit to Growth; Can 'Healthy Aging' Help?

It’s time to revisit one of the Pillars of my three major forces approach: demographics.1 It gets less attention than (de)globalization and technology because it is a slower moving theme, but there are some notable developments worth considering.

Global Trends

The U.N. has published World Fertility 2024. The document the following things we have considered before:

The global fertility rate in 2024 was 2.2 births per woman on average, down from around 5 in the 1960s and 3.3 in 1990. The global fertility rate is projected to continue to decline, reaching the replacement level of 2.1 in 2050 and falling

further to 1.8 births per woman in 2100.

In more than 1 in 10 countries and areas globally, fertility is now below 1.4 births per woman. In four countries – China, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Ukraine – it is below 1.0. If sustained over decades, fertility levels below 1.4 births per woman result in rapid population decline and a pronounced shift in the population age distribution towards older ages

NPR follows the story with some statements about the US2:

In the U.S., this shift is driven in part by a growing number of women deciding against motherhood. According to Kearney, half of American women now reach age 30 without having at least one child. That's a dramatic increase from two decades ago, when only about a third of American women didn't have a child by that age.

The American Demographic Anomaly Comes to an End

The U.S. has chosen to get old fast.

It has been a core thesis of this newsletter that the global economy is being reshaped by the interplay of three major forces: demographics, globalization, and technology. For decades, these drivers provided a powerful deflationary tailwind. We have since established that this era is ending, particularly as global demographic trends, driven by aging populations and falling birth rates, become an inflationary headwind.

A key exception in this story has been the United States. While other advanced economies in Europe and Asia face a steep demographic decline, the U.S. has maintained a relatively stable and younger population. As noted in previous posts, this was not due to a higher domestic birth rate, but almost entirely due to a consistent inflow of immigrants. This was the American demographic anomaly.

New data and a dramatic shift in policy suggest this anomaly has been brought to an abrupt end. The U.S. is now actively choosing to shut down its primary demographic engine. The macroeconomic consequences will be immediate, and the long-term strategic implications—particularly through the lenses of technology and globalization—are profound.

The Immigration Buffer Is Gone

Recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau, detailed in Immigrants drive population growth in a graying America, census shows (WaPo), confirms the underlying trend we have been tracking. The nation is graying rapidly. The number of Americans 65 and older climbed by 3.1% last year, while the population under 18 declined. Eleven states now have more older adults than children, a rapid increase from just three in 2020.

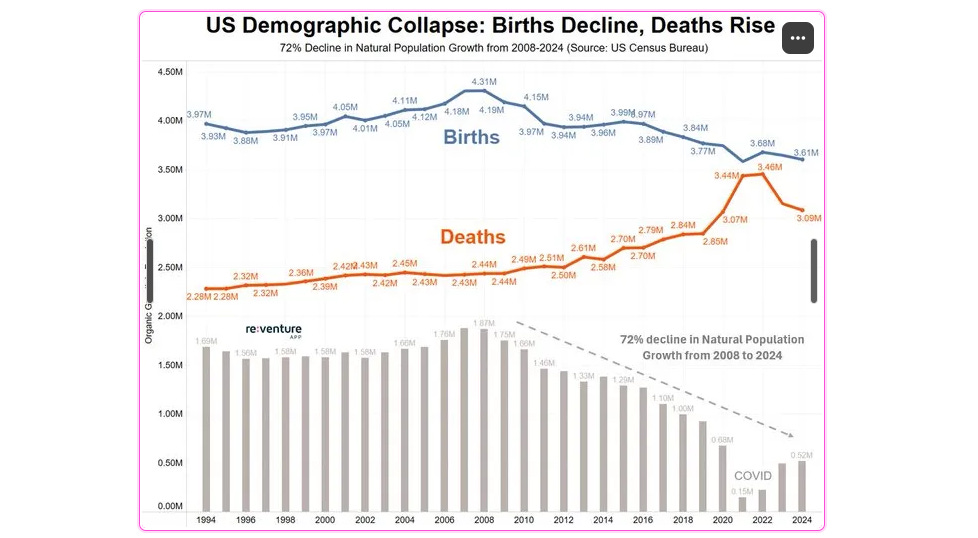

The report adds a crucial layer of detail: this shift is being driven by a "natural decrease" (more deaths than births) in the non-Hispanic White population. For years, this was offset by both higher birth rates and international migration among Hispanic and Asian populations. The chart below, based on Census data, makes this starkly clear. International migration has been the critical growth driver for the Asian population and a major contributor for the Hispanic population, offsetting the decline elsewhere.

This demographic reality has collided with a new policy regime. A July 2025 paper from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), Immigration Policy and Its Macroeconomic Effects in the Second Trump Administration, moves from description to forecast, modeling the consequences of the administration's crackdown. Their conclusion is stark: the immigration buffer is gone.

The AEI authors project a dramatic reversal in population flows. Based on policies already enacted—including the curtailing of legal visas, the effective suspension of the refugee program, and a mass deportation campaign—they forecast that net migration in 2025 will be between -525,000 and +115,000. They add:

we believe it is more likely that net migration in 2025 will be zero or negative than positive.

Quantifying the Shock: A Hit to Growth and the Labor Market

The removal of the primary driver of population growth will have immediate macroeconomic consequences. The AEI paper quantifies this shock:

Labor Force Growth: Potential employment growth, the sustainable pace of job creation, is forecast to collapse. After averaging 140,000 to 180,000 jobs per month in 2024, the AEI's low-end scenario sees this falling to just 10,000 to 40,000 per month in the second half of 2025.

GDP Growth: The sharp drop in net migration is projected to reduce real GDP growth by 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points in 2025.

For years, monthly job numbers well over 100,000 were a sign of a healthy economy. In this new demographic regime, monthly job growth could be near zero, or even negative, simply to keep the labor market in balance.

The AEI analysis offers a nuanced take on inflation. While a shrinking labor force is a classic inflationary supply shock3, the AEI authors argue this will be met by a disinflationary demand shock as the smaller population consumes less. They conclude the net effect on aggregate inflation will be "modest," though prices for labor-intensive goods and services (agriculture, home health aides) will likely rise.

These findings are interesting to consider in light of the administrations strategy: inflationary tariff revenue and juicing GDP growth. The AEI conclusions could suggest a deflationary shock to offset tariff inflation, but a GDP shock to offset growth expectations.

The Global Context: Healthy Aging and the Long-Term View

While U.S. policy creates a self-inflicted demographic crisis, a recent IMF World Economic Outlook4 provides a crucial, longer-term perspective. The report introduces the concept of "healthy aging" as a powerful, but slower-moving, tailwind. People are not only living longer but are also aging with greater physical and cognitive capacity.

The IMF's analysis reveals that these gains are substantial. As their report notes:

when cognitive capacities are the focus, 'the 70s are the new 50s': Data...indicate that, on average, a person who was 70 in 2022 had the same cognitive ability as a 53-year-old in 2000.

This is not merely a sociological curiosity; it has a direct economic impact by enabling longer and more productive working lives. The IMF estimates that healthy aging trends are already poised to contribute 0.4 percentage points to annual global GDP growth through 2050. They further assert that policies such as increasing the effective retirement age and closing gender gaps in labor participation can offset a significant portion of the demographic drag from aging.

Reassessing Through the Three Lenses

Viewing these developments through our framework reveals the interconnected risks of the new U.S. policy.

Demographics: The U.S. is actively choosing to accelerate its own aging process. By shutting off immigration, it is synchronizing its demographic trajectory with the sharp declines seen in Europe and Japan, giving up its primary competitive advantage. It is choosing a future with a smaller workforce and slower growth.

Globalization: We have focused heavily on the deglobalization of goods and capital. The new U.S. policy represents a deglobalization of people. While the IMF notes that migration is a key way for the global economy to efficiently allocate labor from youth-rich to youth-poor countries, the U.S. is unilaterally withdrawing from this system, similar to what we observe in more xenophobic cultures.

Technology: This is where the most severe long-term risk emerges. A restrictive immigration policy does not just affect the number of low-skilled workers; it chokes off the supply of high-skilled talent that fuels innovation. The AEI paper soberly warns of a scenario where

the US will have lost its global competitive edge in technology and higher education. … Scientists, engineers, and students are likely to choose Europe or elsewhere as their preferred destination...possibly leading to new global hubs of innovation that will persist.

For years, the United States stood as a demographic exception among advanced economies. The data is now clear that this era is over. The immediate result is a measurable hit to growth. The long-term risk is that in choosing to get old fast, America is also choosing to become less innovative and less central to the global economy.

As women have far fewer babies, the U.S. and the world face unprecedented challenges

Here are two of my past posts specifically on demographics

Demographics will reverse three multi-decade global trends (Goodhart & Pradhan)