Perspective on Risk - January 21, 2024 - (Capital Requirements)

Point-Counterpoint; Operational Risk Capital; Path Forward; Other Commentary; Stronger Incentives Are Needed; Choose Your Poison; Choose Your Poison; Dudley (Now) Wants Transparency

Point-Counterpoint (on the Basel Endgame)

Anat Admati (tougher on banks) and the Bank Policy Institute (pro-bank) have both recently published on the Basel Endgame

The Parade of Bankers’ New Clothes Continues: 44 Flawed Claims Debunked (Admati)

A Better Way to Assess the Economic Impact of the Basel Proposal (Bank Policy Institute)

Let’s consider them together.

Anat R. Admati and Martin F. Hellwig's article emphasizes the need for transparency and truth in banking regulation debates. Since the GFC, these authors have advocated for drastically higher equity requirements. They argue that many claims in these debates are flawed and misleading, leading to poorly designed rules. The paper is written from a POV that banks should have 100% equity funding, and that her goal is to refute the arguments against her preferred approach. The article is thorough, though. For full disclosure, I’ve never been a particular fan of Admati’s work; I think, as I will immediately discuss, some of her arguments are weak.

For instance, she argues against the risk-weighting of assets:

The claim pretends that risks can be defined and measured in some objective way. The industry also pretends that the banks’ own risk modelers are experts for such measurements. Such pretenses are useful for lobbying but have little to do with the reality of risk measurement and risk management in banking. Allowing required equity to depend on the risk weights attached to banks’ assets creates significant conflicts of interest, not only in relations between banks and supervisors but also in relations between investment units and risk control units of banks.

They also argue that banks are not “special.” Those who have known me for a while know that I consider Corrigan’s 1982 Are Banks Special? to be among the holy books of bank supervision. On these points we just fundamentally disagree,

That said, she has reasonably strong support for her economic arguments, and provides a good deal of citations to relevant studies; better in fact than the BPI paper that I discuss next.

The BPI article, while critiquing the Federal Reserve's Basel proposal, primarily focuses on the operational aspects and potential economic downsides of the proposed regulations, suggesting that they may not be well-calibrated or appropriately tailored. The BPI article raises concerns that the Basel Endgame proposals will have significant negative impacts on U.S. businesses, especially small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They argue that the proposals could lead to higher underwriting costs, reduced liquidity in secondary markets, and increased costs for banks in providing loans to small businesses.

The BPI article supports its economic assessment with specific claims and references, but these should be considered in the context of the piece being advocacy on behalf of the banking industry. The article primarily focuses on the negative impacts without a balanced view of the potential long-term benefits of increased capital requirements, as suggested by the Basel Committee's assessment.

Put another way, the Basel Committee's focus on long-term stability and systemic risk reduction can be seen as a macro-level, long-term approach that prioritize systemic health over immediate business interests. The BPI's emphasis on immediate economic impacts and operational challenges aligns with a more micro-level, short-term approach. The Admati paper is more aligned with the Basel Committee approach and goals.

(Thoughts on) Operational Risk Capital (in the Basel Endgame)

Operational risk capital has been something of a joke in the Basel context. Essentially, when Basel II was negotiated, and they had agreed on internal models for market risk and credit risk, someone said “but what about operational risk” and the dumb, simplistic answer was “we’ll let the banks model that too” despite the fact that, unlike credit and market risk, no banks were really employing models to calculate operational risk capital.

Add to the fact that any and all approaches left the critical infrastructure banks, BNYM, State Street, etc. with levels of capital that felt quite uncomfortable, and clearly insufficient in a crisis. This fact can be seen by when the Bank of New York had to pledge its charter for a loan from the NY Fed when their settlement system went down.1

So it’s no surprise that that the regulators decided they wanted a different approach.

From an external perspective, it seems strange to have individual firms capitalize these exposures. The aggregation and pricing of low or uncorrelated risks is the basis of insurance precisely because this is a more cost-effective solution.

Then add the fact that there are only a very few sources of the types of material operational risks that generate firm-threatening losses. In general, these are either operational issues that are applicable to the payments and securities settlement systems, legal judgments associated with breach of fiduciary duties, regulatory and legal requirements, or counterparty contracts, or trading fraud.

Financial institutions have experienced more than 100 operational loss events exceeding $100 million over the past decade. Examples include the $691 million rogue trading loss at Allfirst Financial, the $484 million settlement due to misleading sales practices at Household Finance, and the estimated $140 million loss stemming from the 9/11 attack at the Bank of New York. Recent settlements related to questionable business practices have further heightened interest in the management of operational risk at financial institutions.

Jerome Kerviel’s rogue trades cost Societe Generale over $7 billion after he evaded numerous layers of computer controls and audits. In the US, large financial institutions experienced tens of billions of dollars of losses due to the improper origination, securitization, and foreclosure practices in the lead up to the 07/08 financial crisis. More recently, Wells Fargo experienced multiple costly operational failures whose full impact has yet to be determined.

While payments/settlement related risks can immediately affect the confidence in individual financial institutions, legal-related losses tend to play out over a long period of time, allowing firms to build the necessary reserves before settlement and payment.

FRB-Richmond Analysis

Much of the Basel Endgame approach to operational risk capital appears based on a study by economists at FRB-Richmond: The Information Value of Past Losses in Operational Risk. Now I normally hate operational risk research, but this looks to be an interesting and informative study. Clearly the data sources have improved since the FRB-Boston did their initial deep dives. And reading this paper changed my priors on some of the aspects of what is being proposed.

From the paper:

We investigate whether the inclusion of past operational losses improves the performance of operational risk models, and generally find that it does even when accounting for a wide range of quantifiable controls.

Past Losses Predict Future Losses

We do not claim that past losses cause future losses, but rather that they predict future losses because they capture hard-to-quantify drivers of exposure. In particular, we believe past losses proxy for banks’ operational risk control quality, risk culture, and risk appetite.

A 1% increase in average total operational losses is associated with a 0.51% increase in expected total operational losses in the ensuing quarter. This coefficient is statistically significant

Across the range of types of operational risk, from fraud to legal risk, operational loss history is predictive of future exposure.

I will have a comment on this later.

Tail Events Are Correlated Over Time

Operational risk exposure is dominated by large, often idiosyncratic, events

We present results for 95th quantile regressions, which correspond to infrequent occurrences (i.e., one-in-twenty-years losses) while not quite to the extreme tail (e.g., the 99.9th quantile used in the operational risk capital standards. A 1% increase in lagged average total operational losses is associated with a 0.74% increase in the 95th quantile of total operational losses in the ensuing quarter; while the regression that separately accounts for loss frequency and severity shows that a 1% increase in lagged average loss frequency is associated with a 0.89% increase in the 95th quantile of total operational losses in the ensuing quarter, and that a 1% increase in lagged average loss severity is associated with a 0.98% increase in the 95th quantile of total operational losses in the ensuing quarter.

From The Paper To The Proposal

Under the proposed approach, a firm’s operational risk capital would be a function of a banking organization’s business indicator component (BIC) and internal loss multiplier (ILM). The BIC would be the sum of three broad categories of activities; Interest, Lease and Dividend Component, Services Component, and Financial Component.

My reactions to reading this approach are leaning negative:

First, I question the purpose of operational risk capital. As designed, it is broad brush affecting far too many institutions. I would focus on those institutions that we feel are materially undercapitalized by the Basel + leverage ratio construct.

Second is that, absent evidence, I do not think that each of the three components of the BIC are equally risky. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston research noted:

the distribution of observed losses varies significantly by business line, but it is not clear whether this is driven by cross-business line variation in the

underlying loss distribution or by cross-business line variation in the sample selection process.

Second, revenue and expenses seem like a weak basis for calculating the risk associated with services. The more efficient I become, and the more savings I pass on to my client, the lower my operational risk charge?

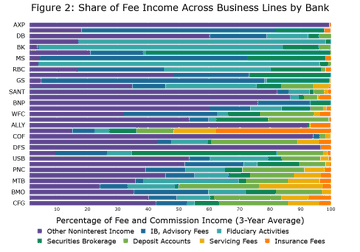

Fiduciary income and processing income are likely not equally risky per dollar of revenue or expense.

One problem with the FRB-Richmond paper is the relatively short time period of the data that they were able to analyze. Not their fault, it’s all that exists:

The final sample in our data consists of 300,549 individual loss events from 38 bank holding companies over the 2000Q1 - 2017Q4 period. This, frankly, is far to short for me to have confidence in their tail estimates.

It would strike me as far easier to marginally scale up credit and market risk capital to cover the operational risk of these activities than to bother with the Interest component and the Financial component.

I was not a fan of the backward looking internal loss multiplier until I read the FRB-Richmond paper. I’m still not thrilled with it, but they seem to have justified their approach. The relatively short 3 year look-back period should not be too onerous.

So in conclusion, If we care about the capitalization of Bank of New York and State Street, let’s address that directly rather than through these academic games.

From a risk manager’s point of view, allocating operational risk capital in this manner will create more noise that proper incentives. A better way is to allocate a fixed amount based on the quality of the business control environment.

The Path Forward for Bank Capital Reform

Fed. Gov. Bowman, the outlier in advocating changes to the Basel Endgame proposal, gave a speech The Path Forward for Bank Capital Reform. Of course I love the speech because 1) it echoes the points I have been making (confirmation bias), and 2) as with Bowman, I have rarely been ‘in consensus’ as a Bank Supervisor.

[Today I will] talk about proposed changes to bank capital rules in the United States and to probe the limits of the notion that "more is better" when regulators seek to apply it to bank capital requirements.

Take the Over

From my perspective, given the significant response from a number of industries and perspectives, as a bank regulatory policymaker, the agencies are obligated to think carefully about the best path forward for this proposal. This should include making substantive changes to address known deficiencies with the proposal and giving the public an opportunity to comment on any reformulated proposal, to ensure the best possible outcome for the Basel capital reforms.

higher levels of capital enhance financial resilience—up to a point.

Increases to the cost of capital … are passed through to customers … in the form of higher costs for financial services or in reduced availability of services ...

Bank Capital Changes Have Broad Implications

The cost of bank capital also influences where activities occur, either within the regulatory perimeter of the banking system or in non-bank entities and the broader shadow-banking system. When the cost of a bank engaging in an activity exceeds the cost of performing the same activity in a non-bank, that cost differential creates pressure that over time leads to a shift in these activities to non-bank providers.

we must consider the broader implications for the structure of the U.S. financial system and for financial stability.

Basel Is An Agreement Among Banks To Have A Level Playing Field

A key element of the Basel capital rules is to promote greater international comparability, a goal that is frustrated when U.S. regulators over-calibrate requirements, at a level in excess of international peers and not supported by proportionate levels of risk. Significant banking activities occur in the international and cross-border context, and we know that financial stability risks can spread throughout global financial markets. One approach to mitigate the spread of financial stability risks is to promote minimum standards across jurisdictions that not only improve competitive equity in banking markets but that also make the financial system safer.

UST Issuance Needs Crack The Leverage Ratio

While risk-based and leverage capital requirements are intended to be complementary and promote the safe and sound operation of the banking system, the eSLR can disrupt banks' ability to engage in Treasury market intermediation, which we saw occur in the early days of market stress during the pandemic. I consider reform of the eSLR to fall in the category of "fixing what is broken."

Addendum

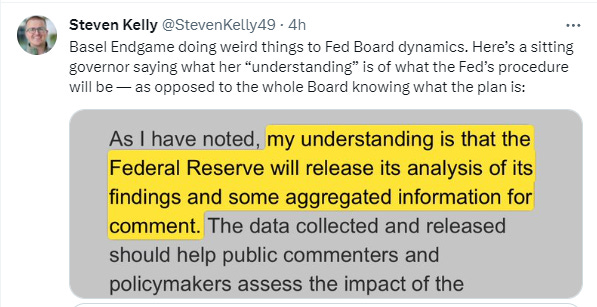

Steve Kelly of Yale pointed to this interesting tidbit.

Barr is keeping things close to the vest amidst some strong industry pushback. While the “over” is still in place, it may soon be time to cover. Politics.

Other Commentary

Some Argue We Need To Stop Diddling Around

Stephen Cecchetti (former Director of Research at NY Fed) and Kim Schoenholtz write in the Washington Post Ignore the bank lobby, regulators. It’s high time for banking reform.

… banks’ preference for financing themselves largely [through debt and leverage] reflects distortions created by public policy. First, though interest payments lower a bank’s taxes, payments (dividends) to investors who provide equity do not. Second, the shareholders of a bank with little equity enjoy an enormous upside when the bank turns a profit, while the creditors (ultimately including taxpayers) bear the risk of bankruptcy when there are losses. Third, for large banks that are perceived as too big to fail, the cost of borrowing is further reduced by the presence of implicit government guarantees.

From the public’s perspective, none of these distortions is relevant. Hence, the social costs of more bank capital are far lower than the private costs. In fact, by countering the factors that distort banks’ preferences, more capital funding can even reduce social costs.

How do higher bank capital requirements make the financial system safer? By creating a buffer against bank insolvency when adverse events lower the value of bank assets.

One frequent objection to higher bank capital requirements is that some risky lending and trading activities will migrate to nonbanks — such as brokers, mutual funds and insurers — without making the financial system safer. However, not all these activities are best funded by bank deposits that are subject to runs and panics, so some of these shifts do make the overall system safer. Moreover, U.S. regulators should aim to treat risks taken by banks and nonbanks in the same way. For example, they can impose minimum down-payment requirements on government-insured mortgages regardless of the lender. Allowing banks to act unsafely is surely not the way to address the possibility of risks migrating elsewhere.

Banks Push Back

Wall Street to Biden bank cops: We’d like European regulation instead

the Basel process has “perversely” not resulted in common standards, with Europeans tending to deviate in ways that reduce capital requirements and the U.S. veering to increase capital requirements.

The EU and U.S. are moving in parallel to implement their own versions of the rules, which are the product of international standards negotiated by banking regulators around the world after the 2008 financial crisis.

Despite global agreement on the high-level details, a transatlantic rift is emerging as the EU and U.S. roll out the rules at home. In Brussels, countries including France and Germany won various carve-outs as they tried to shield their banks from regulatory costs, despite warnings from financial regulators. In Washington, appointees of President Joe Biden have proposed more stringent rules that would force large banks to raise their capital levels by up to 19 percent, including tougher curbs on risky lending to home buyers and businesses.

(Where) Stronger Incentives Are Needed

We saw in the case of Credit Suisse that the firm engaged in the inappropriate facilitation of money laundering for years. The sanctions that were imposed came late and were insufficient to change behavior. I can only wish that the sanctions were more timely; most often those that committed the infraction were gone by the time the regulator considered sanctions, and I do remember hearing comments to the effect that the current management should not be penalized for the misdeeds of their predecessors.

Since we cannot improve the timeliness, we should consider increasing the magnitude of the sanctions. Yes, it may appear unfair to the current management (and possibly shareholders), but stronger sanctions would be a positive externality (especially if combined with significant compensation deferrals or clawbacks).

Anyway, Morgan Stanley got off lightly (FT)

On Friday the US Securities and Exchange Commission charged Morgan Stanley and its former equity syndicate desk head Pawan Passi with fraud in the conduct of block trading business.

… the US Securities and Exchange Commission charged Morgan Stanley and its former equity syndicate desk head Pawan Passi with fraud in the conduct of block trading business. The SEC’s report describes several damningly flagrant breaches of confidentiality

Read the FT post for the details of the trade - doesn’t matter for the point being made.

As Craig Coben writes:

Morgan Stanley has gotten off very, very lightly – a $249mn fine, along with a three-year non-prosecution agreement with the US Attorney’s Office.

[The individuals involved] lost their jobs, careers, and millions of dollars of unvested stock. The investigation also demoralised and distracted Morgan Stanley’s bankers, deflating its market share in equity underwriting.

But this could have turned out a lot worse.

The Department of Justice and SEC were investigating the block trade practices as both a criminal and civil matter.

Morgan Stanley will also be relieved that the probe doesn’t implicate anyone beyond the two syndicate guys. … this is a striking feature of the settlement. After all, Morgan Stanley was earning several multiples more from block trades than its peers. Yet the pattern of misconduct has been pinned entirely on two rogue employees and not on anyone higher up the organisational chain.

Coben is dead right here. Not only could it have been much worse for MS, it should have been worse.

Choose Your Poison

Market fragility or firm fragility?

Bank regulation on capital has made financial system more fragile (FT)

Short-term funding markets have become more fragile largely because of a recent shift in the constitution of the financial system: the segregation of bank capital by jurisdiction.

Until 2016, banks were primarily regulated at a global, consolidated level, by their home regulators. Banks could shift capital more or less seamlessly between their subsidiaries, across products and currencies, as market conditions warranted.

Things changed in July that year, when the Federal Reserve began to require foreign banks with more than $50bn of US assets to set up special holding companies for their local operations. … In 2019, Europe followed suit with a similar set of rules; the biggest US and UK banks were compliant within about a year.

In short, bank capital is trapped. When capital can no longer move across jurisdictions, balance sheets in each region are fixed. It is no surprise that markets have stiffened, and that policymakers now have to stabilise markets more often. The official sector is filling a role that was once left to bank capital.

Before 2016, repo shocks often spilled across borders … Contagion was global … [however] this spread shocks across multiple jurisdictions, reducing their severity.

Now, shocks are more localised. … And as it is now harder for capital buffers to be deployed across borders, the hits are harder. In the US, repo shocks are 26 per cent more frequent than they were pre-2016 and 31 per cent more severe, and tend to last much longer.

Further regulations, mandates and constraints are likely to compound this calcification of markets.

Choose Your Poison

Big Banks Are Supposed to Fail Without Causing Panics. Is That Even Possible? (WSJ)

“It is shocking to me that after 15 years of costly reform efforts, we still couldn’t resolve even a $200 billion bank like SVB without extraordinary government support,” said Jonathan McKernan, a Republican member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

… the bank failures in the U.S. and in Switzerland have exposed gaps in the regulatory regime built up after the 2008 bailouts

Some former U.S. officials say that while the big-bank wind-down plans might seem credible on paper, it is doubtful any regulator would actually rely upon them in a crisis. Daniel Tarullo, a former Federal Reserve governor who was the central bank’s point person on regulation, told the Brookings Institution recently that officials might not think even a modest risk of igniting a larger meltdown by allowing a megabank to fail would be worth taking.

Bill Dudley (now) Argues For Transparency

Amazing how ones view changes depending on the role they inhabit. Bill Dudley now argues for more transparency of supervisory findings about bank weaknesses in If Only We Knew the Problems Facing America's Banks (Bloomberg).

Some well-placed transparency could go a long way toward creating a much-needed sense of urgency.

Better disclosure is amply warranted. This would presumably include MRIAs that are costly to remediate or have a material impact on the bank’s profitability and viability, as well as 4(m) agreements that limit acquisitions or expansions. It might also encompass downgrades (and upgrades) of supervisory ratings (though these might be less useful, as they can’t always be tied back directly to specific issues).

Bill was the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 2009 to 2018. However, if you do a Google search you will not find him advocating such transparency during the time he was President. Not with the Carmen Segarra/Goldman Sachs imbroglio (in fact, I believe the NY Fed fought to preserve the confidentiality of the supervisory records in a lawsuit by Segarra), not with the London Whale (where the Fed evidently had four years of knowledge).

Snark aside, I think there is room for some additional disclosure along the lines that Dudley advocates. 4(m) agreements seem like a no-brainer. Supervisors classify too many issues as MRIAs for me to advocate disclosure.

Supervisory ratings (and downgrades) are interesting to consider. One might already be able to infer to some degree supervisory ratings and downgrades as bank CAMELS ratings are a component of deposit insurance premium calculations.

Dudley does raise an interesting issue at the heart of disclosure; how will bankers and supervisors incentives change?

… the added transparency would provide a powerful nudge to bank managers and directors: If their response wasn’t credible, shareholders would flee and the share price would plummet.

Immediate disclosure, however, could unduly restrain supervisors: They might be hesitant to issue negative findings for fear of provoking deposit outflows or customer defections that would make things even worse.

But he continues with an inadequate fix to the supervisory restraint issue:

This would give bank management enough time to fix simpler deficiencies, and to develop plans to address more complex issues — and to begin implementation — before disclosure was required.

4(m) agreements, MRIAs, and ratings downgraded below “satisfactory” almost by definition will require more time to resolve. What the time will do is allow the firm to prepare for the disclosure by reducing its risk profile, building liquidity and capital buffer, and making management changes.

An excellent detailed summary of the payments and settlements disruption cause by the terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001 is Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve following Sept. 11, 2001 (Fed working paper 03-16) Authored by Jeffrey Lacker. See footnote 29.

Great article and thanks for the trip down memory Lane. Still shake my head that the bosses came back with a pilar 1 charge on ops risk back in 1999