Perspective on Risk - August 4, 2023

Risk Premia Are Low; Jamie Dimon, Robin Wigglesworth, Jay Newman … Commentary on Capital Proposal; Fitch, please.

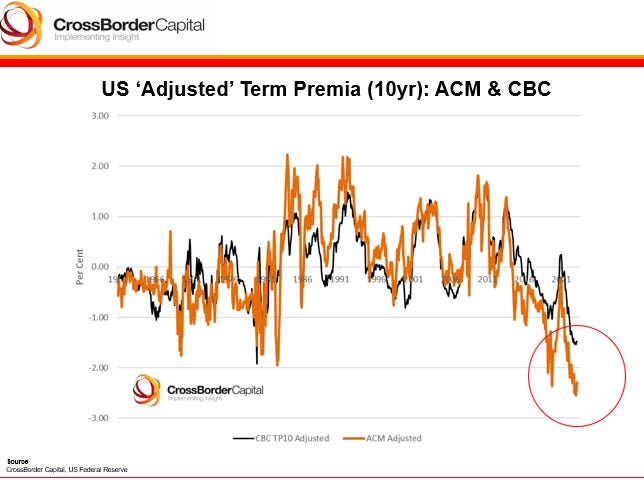

Risk Premia Are Pretty Low

Both equity risk premia and bond term premia. There are different ways of measuring these things, and I’m not sure the equity estimate is the best out there, but they are readily available.

Forward returns may not be what they appear.

When Jamie Dimon Speaks …

A couple of thoughts coming together here. Maybe more interesting to my former regulator colleagues. Good set up for future discussion about financial market structure.

Mr. Dimon was on CNBC’s ‘Power Lunch’ with Leslie Picker and had some important (and depressing) things to say. It’s in a number of separate clips (1, 2, 3, 4). I want to highlight two of his comments.

We don’t have any conversations [with the Fed] anymore. We should be having conversations with regulators about what they’re worried about, what we’re worried about, there’s almost none of that. It’s both lack of transparency and lack of conversation with real practitioners. A lot of people in ivory towers with real opinions, they’ve never been in the real world.

This shows how far we have fallen. During my tenure at the Fed, and particularly at the end, the dialogue was perhaps the most important element of ‘macroprudential’ or ‘financial stability’ work. Bank supervisors spoke with the bankers; the Markets desk spoke with the dealers; other folks like Haley Boesky spoke with hedge funds. The NY Fed was an information gathering operation. I often told folks that their job was akin to being a reporter or a CIA analyst with access to lots of non-public information, but the value was in piecing the picture together. But following the GFC, it was convenient for the folks in DC to blame, in particular, the NY Fed for the crisis, and to strengthen the supervision nexus in DC, adding distance to the bank-regulator relationship, and breaking the advantage NY had with Supervision, Markets, Foreign Central Bank Relations (by virtue of both Markets and the gold vault) and Payment System all under one roof.

There is also a hubris that Mr. Dimon is highlighting. For the most part, regulators could trust the banks to run themselves in a prudent manner. The old Reagan ‘trust but verify’ approach. When we had findings or observations, for the most part we would describe what we had found and let the banks craft and execute remediation plans. If we couldn’t trust bank management to do the right thing, we had much bigger issues. But over time, and with DC centralization, these too became more formal. Instead of sharing our findings and requesting remediation, examiners issued ‘Matters Requiring Immediate Attention.” George Carlin would have been proud.

This can be seen in the approach to capital regulation as well. Basel II was developed with considerable input from the banking community, building off of their best practices. And here regulators still just set the minimum capital requirements until the necessary advent of the DFast stress test.

As I’ve said before, the stress test was definitely fit-for-purpose. It delineated capital needs and granted an implicit understanding that banks that met the threshold would not be closed. But rather than being a one-time fir-for-purpose exercise, many became enamored of the new tool. But the result was that banks no longer determined their capital level, regulators did. Regulation crowded out risk management (at many, not all, firms).

The second set of quotes I want to highlight references the structure of the financial system.

When Leslie Picker stated that the capital rules will ‘send business to the non-bank financials, to the unregulated..” Jamie responds with:

That’s not always bad, I’m not against competition. …

But people should be analyzing the consequences and saying ‘we want that to happen because it’s better for America … I’ve never heard that statement. I think a lot of these things are done without any forethought about the consequences … we need to be very careful … this has been going on for 15 years.’

If they want to push all of the mortgages and small business [out of the large banks], so be it. They should say that.

Hedge funds and private equity are dancing in the streets [because of the Basel end-game capital proposals].Bad policymaking, bad regulations [has slowed down US GDP growth].

Fifteen years caught my ear. 2008, immediately after the GFC. And he is correct. Since that time regulation has been a political lurch towards higher bank capital levels. Witness the rhetoric following the recent SVB and Signature failures. But this does not make it correct.

After I left the Fed, I attended a conference where the head of Bank Supervision for the Federal Reserve was giving a presentation. I challenged him then (what, meek Brian challenging an official?) to provide an affirmative vision of what the Fed wanted the FINANCIAL SYSTEM to look like; were banks to just be intermediaries, or were they to be asset holders? Just liquidity providers, or actual businesses. I asked this same question of his successor. As you might imagine, I never got an answer, and it was clear that they had fallen back into their narrow niche of thinking exclusively about the firms they regulate.

Having subsequently worked in insurance, this question particularly came up when we were a Fed regulated SIFI. What role did the Fed expect insurers to play? How did they feel about insurers owning very long duration assets to match against liabilities like life insurance policies? Etc.

Jamie has highlighted that they still haven’t had that discussion internally, but are just muddling along.

The Bank / Non-Bank Boundary

In the last Perspective, I highlighted that I would be reading A Macroprudential Perspective on the Regulatory Boundaries of US Financial Assets from the folks at Yale’s Journal of Financial Crises. It is worth discussing this paper in light of Mr. Dimon’s subsequent remarks.

My quick summary if you don’t want to read the rest:

Regulation has expanded to capture more of the assets in the US financial system

Activity-based regulation has supplanted institution-based regulation for one-third of regulated assets.

Credit expansions lead to an increased share of assets falling under regulation; however the opposite was true going into the Global Financial Crisis, which coincided with a cyclical contraction of the regulatory perimeter as unregulated institutions played a larger role in credit intermediation during this period.

Now to the paper and a more detailed discussion:

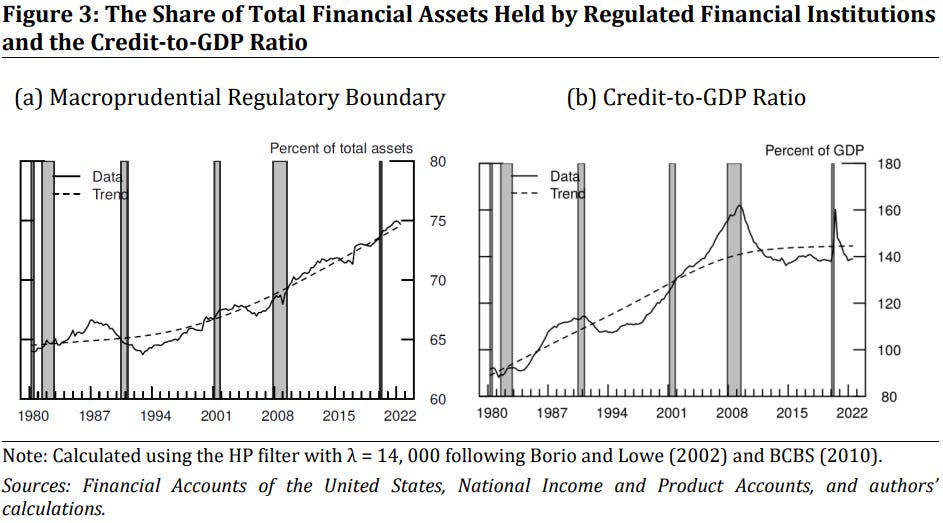

This paper uses data from the Financial Accounts of the United States to map out the regulatory boundaries of assets held by US financial institutions from a macroprudential perspective. We provide a quantitative measure of the macroprudential regulatory boundary—the perimeter between the part of the financial sector that is subject to some form of macroprudential regulatory oversight and that which is not—and show how it has evolved over the past 40 years.

The conclusion surprised me, and has caused me to begin to rethink some of my priors. The paper looks at assets held by US institutions, so importantly may not capture assets held outside of the US (Cayman) and by some non-US entities (sovereign risk funds). From the paper:

We document the gradual expansion of the macroprudential regulatory boundary over the past 40 years.

Our measurement exercise shows the share of assets held by macroprudentially regulated financial institutions relative to total assets—a proxy for the macroprudential regulatory boundary—increased steadily over this period, rising from roughly 65% in the early 1980s to about 75% in the most recent data.

It is important here to understand their definition of which firms are macroprudentially regulated:

Each financial entity … falls into one of three mutually exclusive categories:

those entities prudentially regulated by a federal banking agency, including the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), or the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA);

those macroprudentially regulated by agencies other than a federal banking agency, including securities market regulators such as the SEC and CFTC, as well as state insurance regulators and the regulators of government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), including the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and the Farm Credit Administration (FCA); and finally,

entities that are not macroprudentially regulated, which includes self-regulated organizations or institutions that have only aspects of consumer or investor protection.

So their definition would capture banks, where entity-based prudential regulation occurs by design, as well as the more activity-based regulation of the CFTC and SEC. Not everyone will agree with this definition.

Rapid expansion of intermediation outside the traditional banking system has reduced the regulatory footprint for federal banking regulators, including the Federal Reserve, relative to other agencies. In contrast, the regulatory reach of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has expanded, as assets held by nonbank financial intermediaries now constitute a larger fraction of total assets in the financial sector.

In the early 1980s, roughly two-thirds of all financial assets within the boundary were held by DIs, whereas OFIs held only about 10% of regulated assets. Over the next 20 years, the rapid growth of nonbank financial institutions within the regulatory boundary produced a striking shift in the structure of the financial system from a macroprudential regulatory perspective. The footprint of the banking sector steadily declined, as the share of assets held by DIs fell to about one-third by the early 2000s. At the same time, the share of financial assets held by OFIs within the boundary increased more than three-fold, peaking at nearly 40% on the eve of the GFC.

In the mid-1980s, the Federal Reserve had regulatory responsibility for about one-half of all assets held within the macroprudential regulatory boundary. The expansion of market-based finance over the next 20 years decreased the regulatory reach of the Federal Reserve, which fell to 30% of assets within the boundary leading into the Global Financial Crisis. Coming out of the Global Financial Crisis, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 expanded the regulatory reach of the Federal Reserve to the neighborhood of 35% of assets within the boundary.

The aftermath of the financial crisis resulted in a sharp drawback in the share of assets held by OFIs, but growth in this sector resumed thereafter, with the share of assets of OFIs within the boundary surpassing the share held by DIs in 2017. In the most recent data, OFIs had the largest footprint in the regulatory boundary at 39.7% of all assets on the balance sheet of these institutions, followed by DIs (34.2%), insurance companies (13.1%), and government-sponsored enterprises (12.8%).

So this is an important result; between the early 1980s and the GFC one-third of the assets moved from institution-based regulation to activity-based regulation.

This compositional shift has two important implications for macroprudential policy.

First, the main macroprudential tools available in the US that can be deployed over the cycle are bank stress tests and the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB). Both tools are under the purview of federal banking regulators and operate through bank holding companies (BHCs). Our measurement exercise suggests that, taken together, these tools reach only about one-third of all macroprudentially regulated assets, and this estimate leaves aside assets held on the balance sheets of financial institutions outside the regulatory boundary.

Although the BHCs that are subject to stress testing are some of the largest and most systemically important in the financial system, the figures reveal that they account for only about 20% of total assets within the boundary. Another prominent macroprudential tool is the CCyB. The CCyB is a time-varying capital buffer that can move up and down between 0% and 2.5% of common equity Tier 1 capital as a share of risk-weighted assets. … However, its reach is even more limited than stress testing’s, as eligibility depends on a larger total asset threshold compared to DFAST. As long as macroprudential tools are limited to implementation through the banking sector, their reach will be restricted, and even more so as market-based financial intermediation plays a larger role in financial activity.

The second implication comes from the fact that both the SEC and the CFTC tend to engage more actively in the regulation of market activity rather than direct regulation of the institutions that participate in those markets. As a result, the growing regulatory footprint of these two agencies over the past 20 years places increasing importance on market monitoring and regulation as opposed to monitoring and regulation from an institutional perspective

Cyclical Fluctuations In The Regulatory Boundary

Cyclical fluctuations in the regulatory boundary can be informative for understanding the nature of credit cycles. From a financial stability monitoring perspective, expansions of the credit cycle that are concurrent with a cyclical decline in the regulatory boundary are of particular concern as this is an indicator that credit growth is concentrated among the least resilient institutions

Plotting the cyclical component of the regulatory boundary (the solid black line in Figure 4) alongside the credit cycle (the red dashed line) reveals some interesting information about the nature of credit cycles over time.

The correlation between the credit cycle and the cyclical component of the regulatory boundary over the first 20 years of data presented in this paper is 0.65. In other words, the expansion of credit during this period occurred in combination with a cyclical expansion of the regulatory boundary, that is, an increase in activity of macroprudentially regulated financial institutions relative to their unregulated counterparts.

In contrast, the opposite is true of the expansion of credit going into the Global Financial Crisis, which coincided with a cyclical contraction of the regulatory perimeter as unregulated institutions played a larger role in credit intermediation during this period.

So integrating Mr. Dimon’s comments with the findings of this paper, there is considerable risk when credit expansions occur while the regulatory parameter is shrinking. Or in other words, do we want to push assets and businesses out of the regulated financial sector to the unregulated sector? It didn’t work well last time.

(and remember folks I’m a frickin libertarian)

When Robin Wigglesworth Writes …

In the FT, Robin Wigglesworth has an interesting history of the development of the bond market: How bonds ate the entire financial system (FT). Embedded therein, he raises many of the concerns we have spoken about above:

“Shadow banking” is what some academics call the part of the financial system that resembles, but falls outside traditional banking. Policymakers prefer the less malevolent-sounding — but almost comically obtuse — term “non-bank financial institutions”. At $240tn, this system is now far bigger than its conventional counterpart. … The question of how to tame shadow banking is one of the thorniest topics in finance today.

If the ultimate goal is to regulate the temperature of an economy by changing the cost of credit, then the fact that credit is increasingly extended by the bond market rather than banks inevitably has consequences. The market’s decentralised nature means that dangers can be harder to monitor and address, requiring massive, untargeted “spray-and-pray” monetary responses by central banks when trouble erupts.

Unfortunately, the custodians of the financial system have yet to fully grapple with those consequences, even if everyone from the Federal Reserve to the IMF has repeatedly warned about the multi-faceted dangers the shift from banks to bonds entails.

As BlackRock’s Fink argues. “Historically, bank regulators — whether they do a good or bad job — understand macroprudential risk a lot more than security regulators. But security regulators are now responsible for more of the economy than bank regulators,” he warns. “There are some gaps now.”

After the disaster of 2008 we scrambled to fix and reinforce the breakdown-prone banking system. But we have done little to nothing when it comes to the bond market. That could turn out to be a bigger problem than anyone wants to admit.

Continuing with a theme, Tracy Alloway and Michael Mackenzie have a companion piece: Bonds: How firm a foundation? where they question the opacity of the bond market, and the possible inadequacy of oversight.

On the eve of the financial crisis, the office of market supervision at the US securities watchdog included more than 100 employees charged with monitoring stocks and options, two people keeping an eye on $3.5tn worth of municipal bonds, and no one dedicated to the $5.4tn corporate bond market, where thousands of companies sell their debt.

While a lot has happened in the markets in the seven years since, not much has changed at the US Securities and Exchange Commission unit.

The article goes on to describe some practices that some consider questionable, but not illegal:

One former credit trader at a bank recalled keeping track of which clients do the most “favours” for the firm to ensure good allocations in desirable new deals. … Others described their competitors creating fake orders to get more bonds that could then be given to their biggest clients.

Because rules for bond allocations are not set in stone, most bankers and fund managers do not believe they are doing anything illegal, though some expressed misgivings about a practice they describe as more art than science. … The former trader describes the business of bond allocation as a “regulatory nightmare”

The problem here is that these are the practices market participants are admitting to; there is likely worse if one lifts the covers.

I am in particular reminded of a bank where we found a pattern and practice of ex-post allocation of winning and losing trades. The winners went to a well-known, prominent investor while the losing trades were allocated to smaller and less profitable relationships.

When Jay Newman Writes…

I was turned on to following Mr. Newman long ago by a very senior colleague at the Fed. Mr. Newman works for the activist investor Elliott Management, and has a long history in sovereign debt restructuring. In this FT Alphaville piece, The CoCo Pops lawsuit revisited1, he revisits the treatment of Credit Suisse’s AT1 bonds.

What makes the AT1s worth a hard look is a rare confluence of factors: proceedings before Switzerland’s Federal Administrative Court (FAC), stonewalling by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) in the FAC proceeding, an investigation by the Swiss parliament, a ham-fisted government cover-up, and the very real possibility — I’d say high likelihood — that additional legal actions will be brought in common law jurisdictions before long.

The fundamental question is whether, when it comes to local law bonds, a sovereign can get away with doing what it pleases. Surprisingly, this question bedevils Switzerland

There’s no question that — under certain circumstances — FINMA and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) have the authority to cancel the AT1s. But that prerogative only kicks in if a Swiss bank experiences a “viability” event: defined as the bank being undercapitalised. Even then, a viability event, in and of itself, is insufficient. Only if a bank is undercapitalised and Swiss authorities provide financing to support the capitalisation of the bank can the AT1s be cancelled. Financing provided merely to enhance liquidity doesn’t count.

Here’s the rub: FINMA, the SNB, and CS said before the deal and at press conferences after the fact that CS was not undercapitalised. It had a liquidity problem. The prospectuses and bond documents state clearly that liquidity issues do not trigger writedowns. Swiss authorities did offer emergency financing to CS — specifically to provide additional liquidity.

The Smoking Gun: The Swiss Federal Council, essentially the executive branch, retroactively introduced new rules (Articles 5a, 10a, and 14a of the Emergency Ordinance of 16 March 2023) adding emergency liquidity financing to the list of circumstances under which FINMA could authorise a write down.

Given the scale of the losses, the lack of transparency, and the arrogance and audacity of the cover-up, it seems inevitable that litigation will proliferate, spilling over into common law jurisdictions (the US the UK) where disclosure and discovery can force the Swiss authorities to open their files. When that happens, the gloves will be off. Legal actions won’t be limited to polite administrative review of FINMA’s March 19 order. We’ll see full blown lawsuits directed at FINMA, the Swiss National Bank, and UBS. For students of sovereign debt, there will be plenty of theatre

Commentary on Capital Proposal

Karen Petrou writes Two Tenets of the Capital Proposal That Make No Sense No Matter How Much One Might Want to Love The Rest of It. Remember her clients are the banks.

Some of [the capital proposal] makes absolutely no sense even if one agrees with the agencies’ goals.

Big banks must hold the higher of the old, “general” standardized approach (SA) or the new, “expanded” SA. … Do the agencies not even trust themselves to set capital standards … it’s clear the new, double-barreled approach has still other unintended consequences. … it’s simply impossible to know how much regulatory capital must be held against a low-risk mortgage because of the interplay of the old and new SAs with the proposal’s decision to end capital recognition of mortgage insurance …

Can’t the regulators do the proverbial walk and still chew gum? Apparently not.

Fitch, please.

Fitch downgraded the US to Aa+ from Aaa. The US is now less creditworthy than Microsoft and J&J. Anyway, the US has not met the criteria for being Aaa for quite some time. S&P downgraded the US in 2011. And I’ve had a couple of cantankerous Chief Credit Officers arguing for a US downgrade even before that.

CoCo Pops is a play on words for CS’s Contingent Convertible (CoCo) securities that failed to be deliverable securities for credit default swap purposes.