Perspective on Risk - August 30, 2023

Jackson Hole & IMF Conference on Geopolitical Fragmentation; Economic Normalization

Topics on Central Banks Agenda

Probably everyone is aware that the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City just held its annual Economic Symposium, colloquially known as Jackson Hole. This year, the Federal Reserve conference focused on Structural Shifts in the Global Economy.

What I found interesting is how the topics at Jackson Hole aligned with another recent conference in May, IMF Conference on Geoeconomic Fragmentation.

Fragmentation and ‘slowbalization’

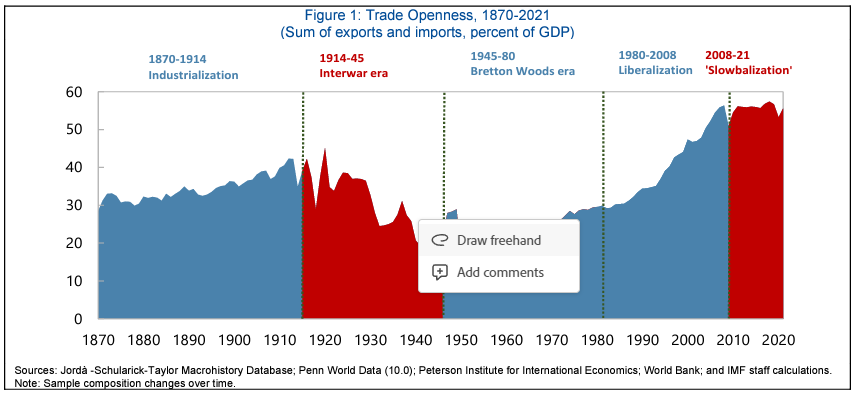

The IMF started with, and Jackson Hole ended with, commentary on globalization. At the IMF they discussed Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism that discusses the various channels (trade deepening, cross-border migration, capital flows) through which the benefits of globalization propagated, the adverse consequences of fragmentation, and ways to protect some of the benefits.

Depending on modeling assumptions, the cost to global output from trade fragmentation could range from 0.2 percent (in a limited fragmentation / low-cost adjustment scenario) to up to 7 percent of GDP (in a severe fragmentation / high-cost adjustment scenario); with the addition of technological decoupling, the loss in output could reach 8 to 12 percent in some countries.

GEF could strain the international monetary system and the global financial safety net (GFSN). Financial globalization could give way to “financial regionalization” and a fragmented global payment system. With less international risk-sharing, GEF could lead to higher macroeconomic volatility, more severe crises, and greater pressures on national buffers. Facing fragmentation risks, countries may look to diversify away from traditional reserve assets —a process that could be accelerated by digitalization— potentially leading to higher financial volatility, at least during transition. By hampering international cooperation, GEF could also weaken the capacity of the GFSN to support crisis countries and complicate the resolution of future sovereign debt crises.

At Jackson Hole, BoE Deputy Gov. Broadbent gave practical examples from The economic costs of restricting trade: the experience of the UK. His is a wide-ranging discussion that discusses reasons for “slowbalization” following the GFC (Russia, Covid) but also highlights that the benefits of global value chains may have peetered out:

Thanks to a succession of regional agreements, progress on multilateral rules and, in 2001, China’s accession to the WTO, average tariff rates declined significantly in the years ahead of the GFC. In Europe, the EU’s expansion, and the creation of the single market, removed many non-tariff barriers (Dhingra et al, 2022). Perhaps it was always going to be difficult to maintain that rate of progress.

And, as Antras (2020) argues, many other factors contributed to the expansion of trade and they too were always likely to run out of steam, or at least to decelerate, at some point. By dramatically reducing the costs of information exchange and improving the efficiency of supply chains, the ICT revolution also made it easier to disperse manufacturing across different countries. Political developments brought significant numbers of people – from Eastern Europe and above all China – into the global economy. The growth of air freight and improvements in shipping reduced the physical costs of trade.

It’s sometimes presumed that the economic gains from trade come at the price of greater economic volatility. At least as far as aggregate output is concerned it’s not clear this is the case.

In an open economy national income depends not just on GDP but what that output can buy on global markets. In the UK’s more recent history there have been significant shifts in these relative prices. In the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, a period of rapid globalisation, import costs fell markedly (relative to wages and the price of domestic output), boosting real incomes. Over the following few years they then levelled out, mirroring the wider pattern in global trade. The early part of this decade, from mid-2020 to mid-2022, saw dramatic rises in import prices. … Against the backdrop of its departure from the European single market and customs union, which itself has raised the costs of trade, these shocks knocked close to 6% from the consumption value of UK output during that two-year period.

The “fragility” of global supply chains, said to have been exposed by the pandemic, is less obvious. The pandemic was as much a story of higher demand for goods as it was one of lower supply. The restrictions in the flow of goods were widespread – they existed not just between but within countries – and would have impaired that supply even if production had been less dispersed. Judging by the retreat in many of their prices over the past year, global value chains have actually proved relatively robust.

Global Value Chains

Both conferences also had presentations on global value chains. The IMF conference discussed two papers, Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment (Habib, IMF) and Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains? (Freund, UC San Diego); the Federal Reserve discussed Global Supply Chains: The Looming “Great Reallocation” (Alfaro, Harvard)

The Habib paper takes the broadest approach, specifically focusing on the impact of geoeconomic fragmentation on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). It illustrates the complex outcomes that arise from geopolitical tensions and supply-chain disruptions. The paper particularly highlights the strategic vulnerability of large advanced economies like the U.S., Germany, and Korea.

The Alfaro paper narrows the focus to global supply chains and the factors contributing to their stress, such as U.S.-China trade tensions and the Covid-19 pandemic. It provides a detailed analysis of trade patterns, especially the trade-to-GDP ratio for various countries. One of its notable findings is the shift in the U.S. supply chain, where decreases in imports from China correlate with increases in unit values of goods purchased from Vietnam and Mexico.

Finally, the Freund paper offers the narrowest perspective by concentrating on the impact of U.S. trade policies, particularly tariffs, on global supply chains. Utilizing a difference-in-differences approach, it investigates the U.S.'s shift away from China in its imports and whether that has led to more diversification or not. The paper suggests that despite the shift, the U.S. may not have significantly reduced its dependence on China.

Friendshoring

The Habib and Alfaro papers also include a discussion of reshored and friendshored production. Habib notes that there is little evidence of material reshoring, while Alfaro notes that friendshoring to Mexico is occurring.

The IMF had a separate session on this topic, and the notable paper was Economic Costs of Friend-shoring (Schweiger). This paper models the economic impact of friend-shoring using a 20% increase in "iceberg trade costs"1 with countries that voted in favor of a UN resolution condemning the invasion of Ukraine. The key finding is:

This paper estimates the economic costs of friend-shoring using a quantitative model incorporating inter-country inter-industry linkages. The results suggest that friend-shoring may lead to real GDP losses of up to 4.7% of GDP in some economies.

Global Financial Flows

Jackson Hole had a presentation titled Living with High Public Debt by Perspectives’ favorite Barry Eichengreen, with a discussion by Carmen Reinhart. Really wish I could have been a fly on the wall for this discussion. This discussion is less about flows than it is about the high and likely sustained level of debt to GDP across countries. In typically blunt fashion, Eichengreen starts:

Public debts have soared to unprecedented peacetime heights. These high debts pose economic, financial and political problems. Multilateral financial institutions and others have consequently laid out scenarios for bringing them back down.

Our thesis in this paper is that high public debts are not going to decline significantly for the foreseeable future. Countries are going to have to live with this new reality as a semipermanent state. These are not normative statements of what is desirable; they are positive statements of what is likely.

This is a hard paper to summarize succinctly, I could write a whole Perspectives on it alone, and I encourage you to read the whole discussion. He discusses the stock of government debt, changes in the composition of government debt holders, r-g, financial repression, inflation, and debt reduction and restructuring, with a substantial review of relevant literature. He concludes:

Public debts have risen for reasons both good and bad, good in that governments have financed needed responses to macroeconomic, financial and public-health emergencies, bad in that they have borrowed imprudently and failed to retire debt in good times. The result has been increases in debt ratios worldwide, on average from 40 to 60 percent of GDP since the Global Financial Crisis.73 In advanced countries, debt ratios have risen still higher, to nearly 85 percent of GDP on average. In the United States, federal government debt in the hands of the public is approaching 100 percent of GDP. In other advanced economies, debt ratios are even higher.

These trends have led anxious observers, such as Bank for International Settlements (2023) and IMF (2023b), to sound a clarion call for debt reduction. Our message is that debt reduction, while desirable in principle, is unlikely in practice. Primary budget surpluses achieved through a combination of tax increases and spending economies will be difficult to sustain on a scale and for the duration needed to significantly reduce debt ratios – to bring them back down to pre-GFC levels, for example.

Real interest rates, having trended downward for an extended period, now show signs of ticking back up, if for no other reason than that more public debt must now be placed with investors.

Looking forward, the challenges are daunting. Given ageing populations, governments will have to find additional finance for healthcare and pensions. They will have to finance spending on defense, climate change abatement and adaptation, and the digital transition. A growing number of low-income countries are already in debt distress.

For those who want more Eichengreen (Kevin), here is the Oddlots folks conversation with Barry (Spotify link, transcript)

The IMF discussed two papers: Trade Uncertainty and U.S. Bank Lending (Goldberg, Federal Reserve Bank of New York) and Geopolitics and Financial Fragmentation: Implications for Macrofinancial Stability (Catalan, IMF).

The Catalan paper is a discussion of the latest IMF Financial Stability Report that discusses how geopolitical shocks and financial fragmentation can lead to increased macro-economic volatility and financial stability risks (mostly through the banking channel).

The Goldberg paper highlights how trade finance uncertainty can contribute to a broader credit contraction. I haven’t read this paper in depth. Abstract:

When trade uncertainty directly affects credit supply it can amplify other contractionary impulses from a deterioration in the international trade environment. Exploiting heterogeneity in banks’ ex-ante exposure to trade uncertainty and loan-level data for U.S. banks, we show that an increase in trade uncertainty is associated with credit contractions that impact broad classes of borrowers and go beyond directly-affected firms. Exposed banks are more likely to curtail lending to firms that are internationally oriented, rely on trade finance, and participate in global value chains. The effects are stronger for banks with business models that support global trade and for constrained banks. Moreover, firms that borrow from exposed banks have worse real outcomes. Our results suggest that trade uncertainty can contribute to a fragmentation between banks and international trade, with negative effects for the real economy.

Technology

The IMF discussed two papers: The Impact of Geopolitical Conflicts on Trade, Growth, and Innovation (Bekkers, WTO) and Sizing Up the Effects of Technological Decoupling (Mano, IMF). Both papers aim to analyze the impact of technological decoupling on global growth. Both papers concern themselves with the impact on technological innovation. The Mano/IMF paper looks at how technological decoupling could affect global growth by altering the dynamics of innovation. The Bekkers/WTO paper also focuses on how geopolitical conflicts can impact technological innovation, albeit through different mechanisms like 'idea diffusion.'

Perhaps my favorite presentation, however, came from Stanford’s Prof. Jones at Jackson Hole. We only get slides from him: The Outlook for Long-Term Economic Growth. He had two slides that remind us of what economic theory says about technology and growth:

And concludes with this question about artificial intelligence:

Can machines augment or even replace people in finding ideas?

The answer is likely yes. Hold this thought. I will revisit this in a future Perspective update on AI.

Other Papers & Topics

Jackson Hole had a notable paper by Fed favorite Daryll Duffie Resilience redux in the US Treasury market. Discussion of this paper doesn’t fit here, and I will probably return to it when we continue our discussions on the future of the global financial structure.

Economic Normalization

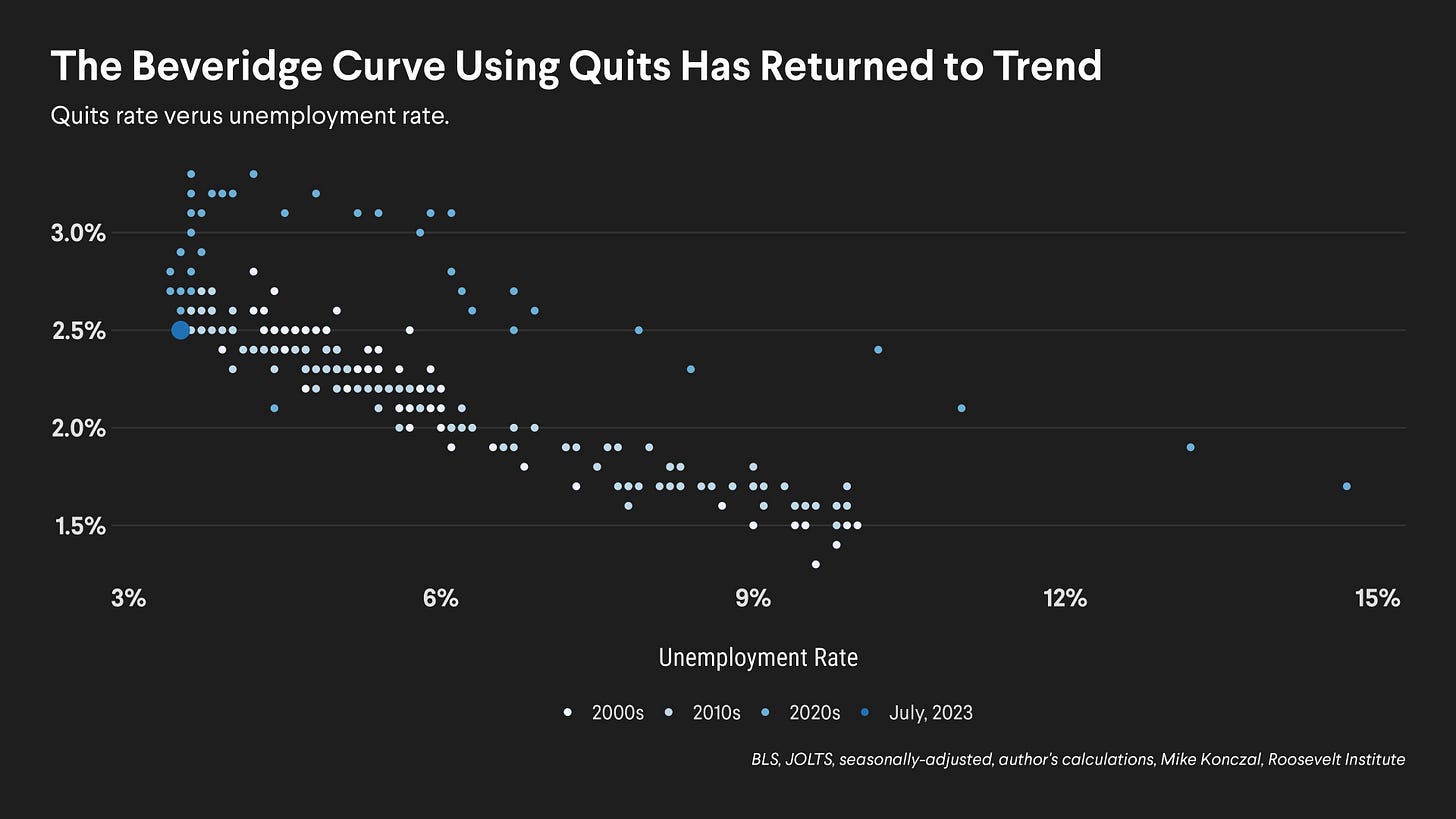

The economy is starting to normalize. The Beveridge Curve, which illustrates the relationship between unemployment and the job vacancy rate, appears on the verge of normalizing after an extended period where it had shifted out. First two graphs from Dario Perkins.

This looks similar to historical experience.

An alternative view (from Mike Konczal), looking at the quits rate compared to unemployment, has already normalized.

This seems consistent with Arturo Estrella’s estimate of when employment traditionally peaks following yield curve inversion (another 4-6 months to peak on average)

The term "iceberg trade costs" is often used in the field of international economics to describe all the costs associated with exporting a good from one country to another, beyond the production costs and the price paid by the importer. These can include transportation costs, tariffs, and other non-tariff barriers such as quotas or regulatory requirements.

The concept gets its name from the idea that just as only a small portion of an iceberg is visible above the water, the final price of an imported good often reflects only a fraction of the total costs associated with international trade.