(1 of 2)

I thought it was a good time to step back and look at the Big 3 forces framework that I use to look at long term trends. The Big Picture discussion evolved out of reviewing Zoltan Poszar’s decoupling work back with this Sept. 1, 2022 Perspective. The thesis is that three factors (demographics, technology and globalization) drive longer-term evolution. I’ve been tempted to add climate change to the mix (but that would mess up the Venn diagram!). The interlocking circles were introduced in a discussion of demographics in the Sept. 16, 2022 Perspective. I last summarized my view in Perspective on Risk - Dec 27, 2023 (Big Picture update)

Globalization/Deglobalization

The demise of globalization has been overdone (at least for now), and the bifurcated world envisioned by Zoltan Poszar does not seem at all close. The dollar is still dominant, as is Chinese goods manufacturing.

Perhaps the one interesting point to note is that China’s foreign deirect investment (FDI) flows have turned negative.

There have been several good papers, written by economists (Baldwin, Eichengreen, Subramanian & Setzer) that I respect, since last December.

The 3rd Big Shift in Globalization (Baldwin)

Globalization and Growth in a Bipolar World (Eichengreen)

Trade hyperglobalization is dead. Long live…? (Subramanian, et. al.)

Richard Baldwin's concept of the "third big shift" in globalization is crucial to understanding the ongoing changes. Baldwin identifies that after the initial phases of trade in final goods and intermediate manufacturing inputs, the global economy is now shifting towards the trade of services. This shift is driven by technological advancements, such as automation and digitalization, which reduce the comparative advantage of low-cost labor in manufacturing and open new opportunities in services. This evolution represents not a retreat from globalization but an adaptation to new economic realities where services, particularly those enabled by digital technologies, become the primary drivers of global trade

Barry Eichengreen focuses more on the challenges posed by geopolitical fragmentation between the United States and China. Eichengreen argues that these tensions are reconfiguring globalization rather than ending it. The rise of protectionist policies, trade wars, and the potential bifurcation of the global economy into Western and Eastern blocs threaten to slow the pace of global trade and investment. These developments introduce inefficiencies and complexities into global supply chains, as nations seek to secure their economic interests amidst rising geopolitical uncertainty.

… global trade has not declined noticeably relative to global GDP. All that has happened is that the rate of growth of trade no longer exceeds the rate of growth of global output of goods and services. Hyperglobalization has given way to globalization pure and simple

Subramanian et. al. and Setzer both challenge the narrative of deglobalization, arguing that while the patterns of globalization are changing, the global economy remains deeply interconnected. Setzer points out that dependence on China has not really decreased. Both authors point out that the adaptability of global supply chains and the continuous integration of emerging economies into global trade networks suggest that globalization is far from over.

Setzer:

… the world economy is still becoming more, not less, globalized—and more dependent on Chinese supply in particular.

A closer look at economic data shows that even though governments have increasingly adopted policies aimed at strengthening resilience, the world economy is still becoming more, not less, globalized—and more dependent on Chinese supply in particular.

Over the five years between the end of 2018 and the end of 2023, China’s exports of manufactured goods increased by 40 percent, from $2.5 trillion to $3.5 trillion, much more than the roughly 15 percent increase between 2013 and 2018.

China’s surplus in manufacturing has risen as much relative to world GDP in the last few years as it did during the first China shock following the country’s accession to the WTO.

Subramanian, et. al.:

First, the end of two decade–long hyperglobalization on is undeniable. Its successor is deglobalization on in goods and continuing albeit slower globalization on in services (“slowbalization”). The goods–services dichotomy is evident across indicators, offering a clue to understanding the post–GFC world.

Second, the GFC marked the end of a three decades–long trend increase in Northern trade exposure to the South. One might call it the end of dislocating or disruptive “comparative advantage,” or Heckscher-Ohlin trade, in the sense of a stabilization of the relative wage/income levels of imports to the North.

Third, at the global level, there is a positive correlation between mercantilism on the one hand and trade globalization and growth on the other. The era of rising and peak mercantilism was also the era of trade hyperglobalization and rapid growth. The decline of mercantilism was also associated with deglobalization and slower growth.

Martin Wolf adds a critical dimension to this discussion by examining the limitations of globalization and the importance of governance in managing its effects. He focuses on managing the balance between global integration and national sovereignty, addressing the inequalities that globalization can exacerbate, and ensuring that global economic systems are resilient to shocks

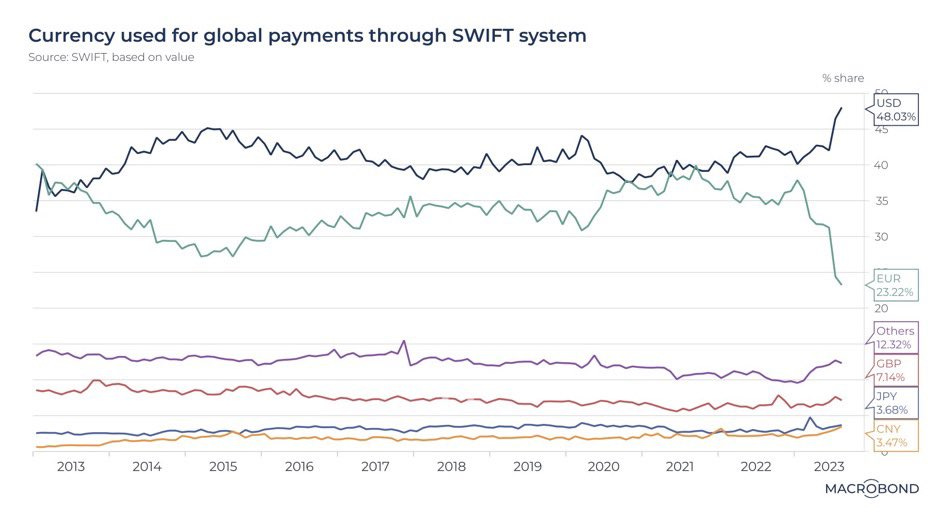

No Signs Of The Dollar’s Demise; USD Is At Highest Usage In A Decade

Bank of Russia Sees No Alternative to Yuan for Its Reserves

Russia’s central bank said it has no better options than the Chinese yuan for its reserves after two years of the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine and the subsequent seizure of its international assets. As of March 22, Russia’s international reserves stood at $590.1 billion, having decreased by about $40 billion over two years of the war, according to data from the central bank.

Pettis’ take:

The numbers aren't huge, but they nonetheless pose an interesting dilemma for Beijing.

Either Russian capital inflows into China must be balanced by a contraction in China's trade surplus, driven either by a stronger RMB or by domestic wealth effects, or, if Beijing wants to avoid that, it must result in more acquisition of foreign reserves or shadow reserves.

In the latter case, this mostly means that the PBoC will directly or indirectly acquire USD, in which case the Russian central bank is transferring a part of what would have been USD reserve acquisition to China. Less Russian exposure to USD means more Chinese exposure.

According to Swift the RMB's share of global payments climbed to 4.6% in November, up from 3.6% a month before. It surpassed the yen for the first time since January 2022 to become the fourth most-used global currency behind GBP, euro and USD.

That’s because:

In March, the renminbi surpassed the U.S. dollar for the first time and became the dominant currency in China’s own cross-border payments, according to China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). Its share of settlement in China’s cross-border payments increased to 47% in 2021, almost double the share five years earlier. Foreigners’ trading of renminbi assets was a big part of the reason for the uptick. China’s currency rises in cross-border trade but remains limited globally (Goldman)

No takers for rupee payment for oil imports (The Indian Express)

India’s push for rupee to be used to pay for import of crude oil has not found any takers as suppliers have expressed concern on repatriation of funds and high transactional costs, the oil ministry told a parliamentary standing committee.

“During FY 2022-23, no crude oil imports by oil PSUs was settled in Indian rupee.

China Imbalances

China represents roughly 17% of global GDP, but while it accounts for 31% of global manufacturing, it only accounts for 13% of global consumption. That's a huge gap between manufacturing and consumption. (Pettis)

FDI Flowing Out Of China

Collapsing foreign direct investment might not be all bad for China’s economy (Chatham House)

For more than a year, the net flow of FDI into China has been increasingly negative. Data released last month by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange indicate that during the year to September 2023, a net outflow of more than $140 billion of long-term investment left China, or just under 1 per cent of China’s GDP. A decade ago, by contrast, China was attracting net inflows of FDI to the tune of around 2 per cent of GDP.

And it’s not just FDI that seems to have had a change of heart about China. Since August this year, international investors have withdrawn some $25 billion from the market for China’s ‘A’ shares, namely those that are denominated in renminbi and listed in Shanghai or Shenzhen.