Perspective on Risk - April 22, 2024

Forecasting Financial Stability; Petrou on Resolution; Financial System Evolution/Shadow Banking; Private Credit; CRE; Wirecard

Forecasting Financial Stability

Anna Kovner, Director of Financial Stability Policy Research at the NY Fed, delivered remarks at the Forecasters Club of New York back in February. I don’t suspect many have read this or even heard of the remarks. But they are very interesting and a good way to discuss the dynamics behind an Irving Fisher approach to financial instability.

Methodology

… an economic shock can trigger a self-reinforcing loop as margin calls impair credit provision [that] lower asset prices and depress economic activity. … financial crises lead to more severe economic downturns ... It is this nonlinear response that creates financial stability concerns and that we seek to gauge in the financial stability outlook.

One approach to quantifying financial stability risks is to estimate the probability of very bad outcomes in real economic variables such as GDP and inflation using quantile regressions that measure the relationship of these variables in bad times instead of just on average.

One way of visualizing the financial stability outlook is to look at the size of the tail of the GDP growth distribution. … when the bad tail is wide, the economy is vulnerable.

A second approach to capturing hidden risks to economic outcomes is examining patterns in the financial system historically associated with the amplification of negative real shocks both in the U.S. and internationally. The Federal Reserve’s Financial Stability Report is anchored in this type of monitoring.

The first vulnerability is high asset prices relative to fundamentals. … The second vulnerability is business and household leverage. … The third and fourth vulnerabilities arise from the financial sector, from both its leverage and the extent of maturity and liquidity transformation.

Financial Stability Vulnerabilities in 2024 and Beyond

I am keeping my eyes on four key financial stability vulnerabilities for 2024 and beyond.

While the banking industry overall is sound and resilient, changes in interest rates have negatively affected the value of long-duration assets and the impact of revaluations of commercial real estate has been unevenly distributed.

A second concern emerging from higher rates is the acceleration of deposits into prime money market funds and stablecoins,

My third area of focus is U.S. Treasury markets. … Treasury market liquidity has been somewhat strained across almost all measures for some time, including bid-ask spreads, market depth, and price impact.

Finally, a key vector for financial vulnerability is cyberattacks. These have been occurring at accelerating rates, so we must work to reduce their amplification though the financial system.

The Leverage Cycle

Kovner’s speech echoes Geanakoplos’ 2010 paper The Leverage Cycle. This is a paper many Federal Reserve policymakers of my day read and appreciated. Geanakoplos builds off Irving Fisher’s work to argue that leverage is determined in equilibrium by supply and demand rather than being fixed exogenously. He describes a cycle of leveraging where leverage tends to increase as lenders become more willing to extend credit and borrowers seek to take on more debt, which of course leads to a deleveraging cycle when there is an exogenous shock to asset values, even with rational agents.

Both Kovner and Geanakoplos emphasize the systemic risks posed by excessive leverage in the repo market and money market funds. The potential for runs and fire sales in these markets can amplify financial distress.

Kovner’s Figure 3 shows that nonfinancial business leverage has been exceeding historical trends. Geanakoplos discusses how periods of high leverage are often followed by deleveraging and a crash in asset prices.

The question becomes, where is the leverage?

The Global Credit Cycle

Yet another paper is relevant to reading Kovner’s remarks: The Global Credit Cycle by NY Fed economists Boyarchenko and Elias.

Do global credit conditions affect local credit and business cycles? … We uncover a global credit cycle in risky asset returns, which is distinct from the global risk cycle. … the global pricing of corporate credit is a fundamental factor in driving local credit conditions and real outcomes.

The important observation here, and in Kovner’s remarks, is that there is a global credit cycle that is distinct from the global risk cycle.

Kovner warns that deteriorations in global credit conditions predict lower average GDP growth and higher probability of crises. Similarly, Boyarchenko and Elias show their global credit factor predicts capital flow episodes, lower real GDP growth, and higher crisis probability at the country level.

In essence, Boyarchenko and Elias flesh out the cycle behind the observations in Kovner.

Further on FDIC’s Orderly Resolution Of Systemic Banks

I wrote in the Perspective on Risk - April 13, 2024 that I was more positive about the FDIC reform than I expected. Karen Petrou is a bit more blunt (and she is probably right).

The FDIC Plan to End Too-Big-to-Fail Brings Promise of More Bailouts

If big banks and systemic nonbanks can’t be closed without bailouts, then moral hazard triumphs and crashes become still more frequent and pernicious. Last week, mountains moved and Chair Gruenberg said that anything big will not be bailed out. Would this were true, but it’s not.

Financial System Evolution / Shadow Banking

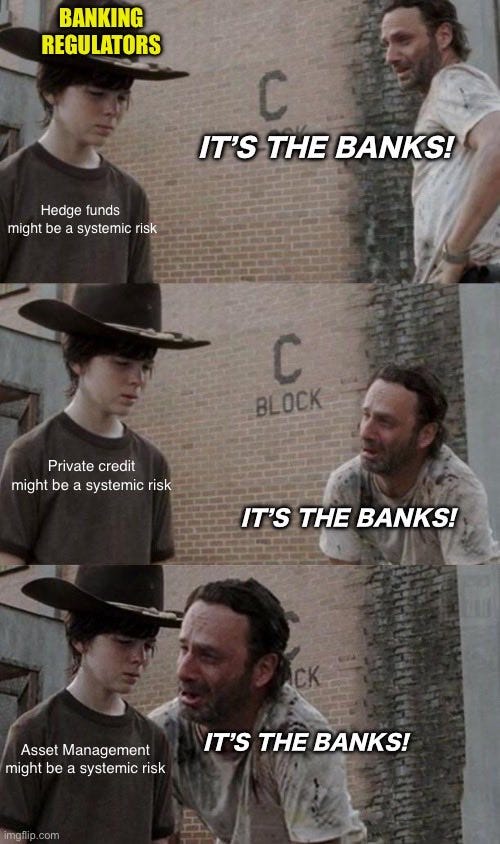

I run the risk here of succumbing to confirmation bias, but this aligns with much of what we have previously been discussing.

Acharya, Cetorelli and Tuckman have authored Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin? You should read this paper as updating and taking forward the Poszar et. al. Shadow Banking paper of 2012.

We argue instead that NBFI and bank businesses and risks are so interwoven that they are better described as having transformed over time rather than as having migrated from banks to NBFIs. These transformations are at least in part a response to regulation and are such that banks remain special as both routine and emergency liquidity providers to NBFIs.

We support this perspective as follows:

The new and enhanced financial accounts data for the United States (“From Whom to Whom”) show that banks and NBFIs finance each other, with NBFIs especially dependent on banks;

Case studies and regulatory data show that banks remain exposed to credit and funding risks, which at first glance seem to have moved to NBFIs, and also to contingent liquidity risk from the provision of credit lines to NBFIs; and

Empirical work confirms bank-NBFI linkages through the correlation of their abnormal equity returns and market-based measures of systemic risk.

[We argue] that neither the parallel nor substitution views adequately describe how activities align across these sectors. Instead, we posit that intermediation activities—including the types of claims held by each sector, the manner of their financing, and contingent liquidity arrangements—endogenously transform across sectors so as

to loosen regulatory constraints and reduce regulatory costs across the financial sector as a whole, along the lines of Goodhart’s Law, and

to harness the inherent funding and liquidity advantages of bank deposit franchises (Kashyap, Rajan, and Stein, 2002) and access to safety nets (Gatev and Strahan, 2006), whether explicitly in the form of deposit insurance and central bank lender of last resort (LOLR) financing or implicitly in the form of too-big-to-fail insurance.

The transformation view of the NBFI and bank sectors predicts that NBFI and bank businesses will be interwoven with complex interdependencies. But, given the special role of banks from their deposit franchises and access to official backstops, NBFIs can be expected to be more liability-dependent on banks than vice versa, and also more liability-dependent on banks than on each other.

They give several examples of how this is occurring in the market; private credit, mortgages, contingency funding, etc.

How should this affect policymaking?

If the transformation view is correct, regulators may wish to consider ex-ante measuring and monitoring of systemic risks, as well as inducing banks and NBFIs to internalize the systemic risks generated by their interdependent intermediation activities. Likewise, they might also consider ex-post state-contingent responses to distresses in the NBFI sector.

The paper then explores the possibility of creating emergency liquidity regimes for both banks and NBFIs. Right now, Jamie Dimon gets to play gatekeeper for the most part. They discuss three regimes:

Committed Liquidity Facilities

Pawn Broker For All Seasons

Federal Liquidity Options.

Policymakers appear to be pursuing option 2, but only with regard to banks. The authors would extend it to non-banks as well. Readers know I am not enamored with the arguments for prepositioning collateral at the discount window preferring instead a regime where the central bank ex-ante sells priced liquidity options. Well it seems as if one of these authors, Tuckman, has beaten me to the punch by over a decade.1 This is close to option 3. I’m disappointed my research hadn’t unearthed this earlier.

Tuckman (2012) proposed that any bank or NBFI be able to purchase options on secured borrowing from the central bank at predetermined haircuts and rates. Furthermore, the central bank would sell a sufficient quantity of FLOs so that it could credibly commit to provide no additional liquidity in a crisis. If this commitment were indeed credible, then ad hoc crisis bailouts would no longer be necessary and banks and NBFIs would use FLO prices to internalize the cost of liquidity in stress scenarios.

While the "Shadow Banking" paper describes the different sub-systems and steps involved in shadow credit intermediation, the "Where Do Banks End" paper emphasizes how intermediation activities have transformed across the bank and NBFI sectors over time. It highlights the role of banks in providing funding and liquidity to NBFIs, as well as the exposure of banks to risks originating in the NBFI sector.

Private Credit

Officialdom seems to continue to worry about “private credit.” The IMF has weighed in with their April 2024 Global Financial Stability Report Chapter 2: The Rise and Risks of Private Credit. Having forced much of the activity out of regulated banking by their capital and liquidity requirements, they want national policymakers to:

Encourage authorities to consider a more intrusive supervisory and regulatory approach to private credit funds, their institutional investors, and leverage providers.

Close data gaps so that supervisors and regulators may more comprehensively assess risks, including leverage, interconnectedness, and the buildup of investor concentration. Enhance reporting requirements for private credit funds and their investors, and leverage providers to allow for improved monitoring and risk management.

Closely monitor and address liquidity and conduct risks in funds—especially retail—that may be faced with higher redemption risks. Implement relevant product design and liquidity management recommendations from the Financial Stability Board and the International Organization of Securities Commissions.

Strengthen cross-sectoral and cross-border regulatory cooperation and make asset risk assessments more consistent across financial sectors.

They come up with the usual list of nasty things that can happen as their justification, while also reporting that market behavior at this time does not appear to warrant concerns.:

At present, the financial stability risks posed by private credit appear contained. … The use of leverage appears modest, as do liquidity and interconnectedness risks.

I think the IMF does highlight one concern: the potential for hidden layers of leverage.

Leverage deployed by private credit funds appears to be low compared with other lenders such as banks, but the presence of multiple layers of hidden leverage within the broader private credit system raises concerns. Leverage may not always be at the fund level, and the entire private credit system can form a complex network involving several potentially leveraged participants, including borrowers.

Private credit investors, funds, and borrowers deploy leverage extensively, forming a complex multilayered structure. Investors such as insurance firms and pension funds may use leverage … Private credit investment vehicles may employ leverage directly within a fund, through special-purpose vehicles or holding companies. Leverage can also be increased through more complex strategies such as collateralized fund obligations, in which the interests of the fund’s limited partners are transferred to a special-purpose vehicle to loosen cash flows and access a wider investor base … In addition, private credit borrowers extensively deploy leverage.

The fear, if we present it in terms of the above papers, is that policymakers may not be able to monitor the leverage, credit or risk cycles due to the migration of activity out of the regulatory perimeter.

But it does strike me that we may be in a fundamentally better structure. We have private sector discipline in credit extension without the agency problems of regulated institutions, and we have private capital at risk before problems hit the banking sector. This makes the core financial system potentially safer, but does nothing to mitigate the behaviors that Fisher, Kovner, Geanakoplos and others worry about.

It is also worth noting that this may be an efficiency gain. Just as larger borrowers can now observe the tradeoff between bank and capital markets funding, smaller non-IG borrowers may now have more options between bank and private credit.

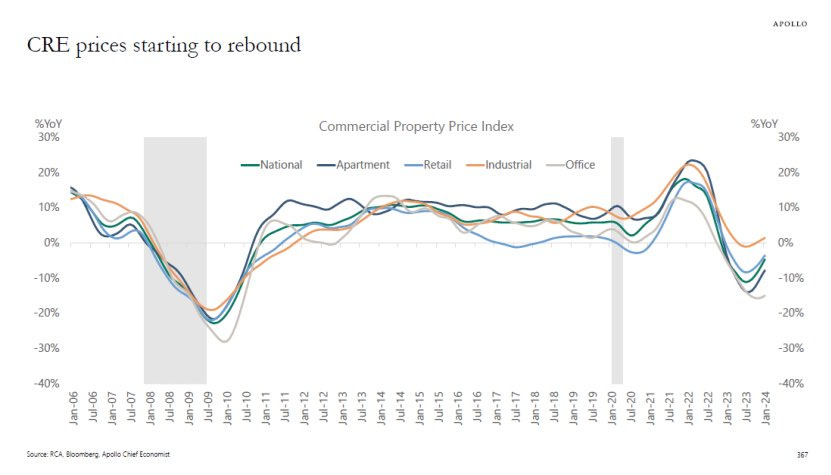

Commercial Real Estate

Fundamentals

Jon Gray Says CRE Has Bottomed

If only we could trust that he wasn’t talking his book.

Blackstone Says Time to Buy Real Estate as Prices at Bottom (Bloomberg)

“The perception is so negative and yet the value decline has occurred, so when you get into this bottoming period that’s when you want to move,”

Update From The WFH Paper Guys

Back in Perspective on Risk - Nov. 17, 2022 I highlighted an NPER paper Work From Home and the Office Real Estate Apocalypse These guys are back with revised views they share in an OddLots discussion: Can New York and San Francisco Escape the Urban Doom Loop? (OddLots). Their key point seems to be that they believe their Doom Loop has long and variable lags.

We are going to be speaking with Arpit Gupta, the co-author of a paper " Work From Home and the Office Real Estate Apocalypse."

… we found is that over the course of the pandemic, the price of suburban real estate … have gone up from massively … relative to real estate in the center of the city.

… across many cities like New York or San Francisco, you see a population loss of about 6-to-8% that happened over the course of the pandemic. And this population loss has sort of stabilized. So San Francisco gained a small amount of population last year. New York continued to lose population, but at a smaller rate than previous years.

San Francisco right now has something like a 37% office vacancy rate. At those rates, if you had the fastest office absorption in history, you would still need seven or eight years just to fill the existing vacant office space. If you are filling San Francisco office at the average rate of absorption over the last 20 years, you would need something like 15 or more years to actually fill all of that office space. So there's just a huge vacancy problem in a lot of these West Coast tech-centric cities. In comparison, New York just has a broad diversity of different industrial uses and you have a lot of firms like big law or financial firms that do seem to be more able to get workers into the office.

More Wirecard

Wirecard fugitive helped run Russian spy operations across Europe (FT)

Fugitive Wirecard COO Jan Marsalek used compromised intelligence officials in Vienna to spy on European citizens and plot break-ins and assassinations by elite Russian hit squads. He also obtained a Nato government’s cutting-edge cryptography machine and smuggled stolen senior Austrian civil servants’ phones to Moscow.

Tuckman, B. (2012) “Federal Liquidity Options: Containing Runs on Deposit-Like Assets without Bailouts and Moral Hazard,” Journal of Applied Finance 2, pp. 20-38.