Perspective on Risk - May 25, 2024 (Back to Banking & Finance)

Aaa CMBS; Haldane the Austrian; Minsky; Barr Gives Specifics; Sternlight; Capital; Clearing Capital; Tarullo's Conversion; Corp. Credit; Intermediation Chains; Bank Runs; Recession?; NYU Symposium

When I devote a couple of PoRs to non-finance stuff, this is what you subsequently get.

This PoR may be too long for Gmail; if so please click over to the Substack site as there is good stuff later in the post.

On Your Marks …

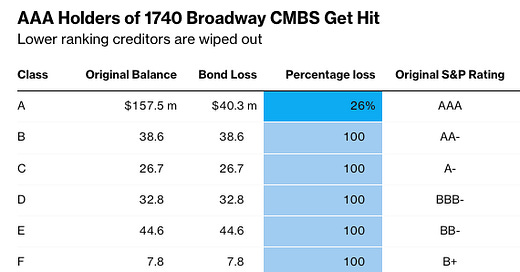

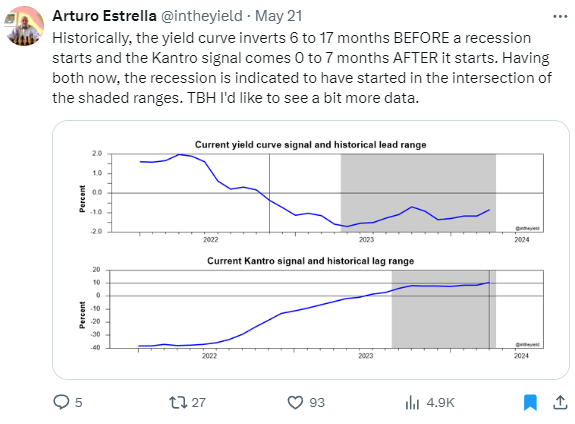

Hat tip to Kevin McGinn for noticing this first: A Really Bad Sign for Commercial Real Estate (Bloomberg)

Buyers of the AAA portion … got back less than three-quarters of their original investment after the loan was sold at a steep discount.

For the first time since the financial crisis, investors in top-rated bonds backed by commercial real estate debt are getting hit with losses. Buyers of the AAA portion of a $308 million note backed by the mortgage on a building in midtown Manhattan got back less than three-quarters of their original investment after the loan was sold at a steep discount. It’s the first such loss of the post-crisis era, says Barclays. As for the five groups of lower ranking creditors? They got wiped out.

This was a Blackstone deal.

Will this time be different?

OK, this so far is one isolated case, and it’s a single asset deal, not a pooled deal, but …

Policymakers worry when Aaa takes losses, because these are generally held by investors looking for “cash equivalent” investments, such as Institutional MMMF. There is always the possibility that the cash investors start evaluating the holdings of the MMMF and seek to take the first-mover advantage and move their funds, which is of course how runs start.

Now, there is not yet any systematic concerns about underwriting incentives, or inappropriate rating agency work, as there was in subprime.

Goldman published US CRE, one year later: Volatile, dispersed, but not systemic

From a credit performance standpoint, the share of loans behind on their debt service payments or being worked out by lenders has increased. But this increase is yet to translate into higher losses on loan portfolios, keeping systemic concerns in check. Lastly, aside from office properties, property operating performance has generally remained resilient, though dispersion across and within property types has been elevated.

… we draw four key conclusions.

The first is that credit availability has been resilient, suggesting the risk of a credit crunch is still remote and leaving us comfortable with our view that the likelihood of a systemic shock from the CRE market is low.

The second is that modifications and extensions will likely remain a key channel through which borrowers address their refinancing needs.

The third is that the resilience of the debt financing backdrop will likely continue to stabilize property performance, especially outside of the office sector.

Lastly, on the market side, we think the magnitude and speed of erosion in the risk premium provided by the new issue CMBS market has shifted the opportunity set to bond selection in older vintages in the secondary market.

But watch this space.

Haldane the Austrian

Andy Haldane is ever pragmatic and iconoclastic. Somewhat surprisingly, but not out of character, he unleashes his inner Austrian-school economist in Why an uncertain world needs to take on more risk (FT).

Stirring Schumpeter from his slumber requires a radical retuning of all our risk-based rules to a growth-first wavelength.

The Great Crash of 1929 left lasting scars on investors’ balance sheets and risk appetites. … Almost a century on, those same behaviours are in play today. Risk-aversion is rife among workers, businesses and governments. Security is trumping opportunity. Economies face a “paradox of risk” — in seeking to avoid risks, we are amplifying them. Rules and regulations put in place to curb risk are having the same, paradoxical, impact.

One measure of this is the combined rate of job creation and destruction — the reallocation rate. Since the start of the century, this has fallen sharply across most OECD countries and most sectors. … Part of the explanation is that … rates of business start-ups have fallen (lower creation). … Fewer, new innovative companies means lower productivity.

At the other end of the lifecycle, fewer businesses have been going bust (lower destruction). … This has resulted in a lengthening tail of low productivity companies, surviving but not thriving.

This risk-averse behaviour extends to financial companies, with bank and non-bank investors also retreating from risk. … This defensive behaviour has now reached governments.

To resolve the paradox, [debt-first fiscal rules] need to be replaced with rules that prioritise growth and seek to maximise national net worth, not minimise gross debt.

The same logic applies to the rules shaping risk in private markets. The Basel III regulatory rules for banks, and the Solvency II rules for insurance companies, were crafted in an era when risk was too high … Ditto for the regulatory rules around competition and corporate governance.

Our uncertain world is generating collective caution. This leaves economies experiencing too little change and bearing too little risk. Well-intentioned safety-ism is making the world less safe. Stirring Schumpeter from his slumber requires a radical retuning of all our risk-based rules to a growth-first wavelength.

Minskey-Kindleberger

The Minsky-Kindleberger Connection and the Making of Manias, Panics, and Crashes (Mehrling)

This article traces the evolution of what has come to be called the Kindleberger-Minsky model, starting with Kindleberger’s 1978 publication of Manias, Panics, and Crashes and continuing thereafter. The key to understand the affinity of the two men, it is argued, is a shared intellectual ancestry in pre-war American institutionalism, which led to shared outsider status in the post-World War II economics academy. Both also identified with the longer tradition of monetary thought that emphasizes the inherent instability of credit, and hence the necessity for central bank management.

Barr Adds Some Specificity

In a recent speech, On Building a Resilient Regulatory Framework, Fed. Gov. Barr gave some additional specificity on supervisory actions being considered. Here are some quotes: if you’ve been following along none of this is too surprising:

We are exploring a requirement that banks over a certain size maintain a minimum amount of readily available liquidity with a pool of reserves and pre-positioned collateral at the discount window, based on a fraction of their uninsured deposits.

Incorporating the discount window into a readiness requirement would also re-emphasize that supervisors and examiners view use of the discount window as appropriate and unexceptional under both normal and stressed market conditions.

We are considering a restriction on the extent of reliance on held to maturity (HTM) assets in large banks’ liquidity buffers, such as those held under the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the internal liquidity stress test (ILST) requirements, to address the known challenges with their monetization in stress conditions.

Observed deposit withdrawals from high-net-worth individuals and companies associated with venture capital or crypto-asset-related businesses suggest the need to re-calibrate deposit outflow assumptions in our rules for these types of depositors.

Unlike capital, which is likely to be depleted by the time a bank fails, long-term debt is available upon failure to absorb losses, providing better protection for depositors, and limiting the potential cost of the resolution to the Deposit Insurance Fund.

As with many things, there are implications to these changes that I hope supervisors are considering:

Restricting HTM inclusion into LCR calculations is a further push towards an MTM view of the asset side of the balance sheet WITHOUT a commensurate push towards an MTM view of liabilities.

Long-term debt requirement is wonderful in the abstract, but the larger issue is that there is huge amounts of short-term uninsured corporate cash in the market that needs a home. The restrictions are saying we do not want banks to be the direct primary liquidity intermediation vehicle. We are pushing this money out of Prime MMMF, and now disincenting banks from taking this money.

Doing Anything To Avoid Capital Calls and Markdowns

Starwood’s $10bn property fund taps credit line as investors pull money (FT)

Starwood Real Estate Investment Trust (Sreit), one of the largest unlisted property funds, has drawn more than $1.3bn of its $1.55bn unsecured credit facility since the beginning of 2023 following heavy redemption requests.

Unlike publicly traded property trusts, in which investors are free to sell shares on an open market, private Reits are able to control withdrawals and avoid a fire sale of assets.

In the first quarter of 2024, Miami-based Starwood granted a diminishing portion of redemption requests. Investors asked for $1.3bn of their money back, but received only $501mn on a pro-rata basis because of a cap on quarterly withdrawals set at 5 per cent of net assets. In March, only about a quarter of such requests were satisfied.

Starwood’s declared net asset value is down more than 16 per cent from its September 2022 peak at nearly $10bn. Private funds have broadly declined to mark down their net asset values as much as listed funds have fallen in value.

Facing Possible Cash Crunch, Giant Real Estate Fund Limits Withdrawals (NY Times)

Starwood Real Estate Income Trust is restricting what investors can redeem rather than sell its properties to raise cash.

Starwood Real Estate Income Trust, which manages about $10 billion and is one of the largest real estate investment trusts around, said on Thursday that it would buy back only 1 percent of the value of the fund’s assets every quarter, down from 5 percent earlier.

Starwood said that it had chosen to tighten the limit because it was facing more withdrawals than it could meet with its cash on hand, and that it was a better option than raising money by selling properties at discounted prices.

How Much Capital Is Enough?

The Bank Policy Institute tweeted a short statement by Rep. Richie Torrez of the Bronx; I couldn’t have put it any better:

When setting capital requirements, there is a tradeoff between safety and soundness … and capital formation ... But the best regulatory outcome lies not in maximizing safety and soundness to the exclusion of capital formation, nor does it lie in maximizing capital formation to the exclusion of safety and soundness. The best outcome lies in striking the optimal balance between the two.

Graham Steele (formerly of Treasury) then tweeted out a reference to this paper form the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis:

An Empirical Economic Assessment of the Costs and Benefits of Bank Capital in the United States (FRB-St. Louis)

We evaluate the economic costs and benefits of bank capital in the United States. The analysis is similar to that found in previous studies, though we tailor it to the specific features and experience of the U.S. financial system. We also make adjustments to account for the impact of liquidity- and resolution-related regulations on the probability of a financial crisis. We find that the level of capital that maximizes the difference between total benefits and total costs ranges from just over 13 percent to 26 percent.

Capital Rules & Clearing

Courtesy of David Merkle, this IFRE article Capital rules add to clearing concentration fears in US$715trn derivatives market

Only 12 banks provide over-the-counter derivatives clearing services in the US – a near 50% drop from a decade ago – with six firms accounting for 84% of activity.

For the clearing system to remain healthy, it needs to retain enough institutions that can step up when the going gets tough.

Tougher capital rules due to go live next year are stoking concerns that the business of banks clearing trades in the US$715trn derivatives market could reach dangerous levels of concentration, amplifying systemic risk when regulators are pushing more activity into clearing than ever before.

Proposed rules could force the largest US banks to increase capital levels by more than 80% for providing derivatives clearing services to clients – the equivalent of US$7.2bn per institution, according to analysis by the Futures Industry Association

Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Nomura, BNY Mellon, State Street and NatWest are among those to have quit the business in recent years.

Some believe the US proposals could help reduce concentration by redistributing activity towards European banks and firms outside the banking system that are looking to grow their OTC clearing franchise.

… clearinghouses rely on their members to help them weather periods of severe market stress and take on client trades that need to be moved and absorbed if another clearing broker is on the point of collapse.

Tarullo Reconsiders

First, the usual disclaimer; I have not been the biggest fan of former Gov. Tarullo all the way back to when I worked at the NY Fed. That said, when he writes about stress testing it is worth reading. He recently authored Reconsidering the regulatory uses of stress testing (Brookings).

Tarullo seems to have had a conversion!

In this paper, he critiques the current use of stress testing in bank regulation, arguing that it has become too predictable and bureaucratic to effectively assess the resilience of large banks, something many of his detractors have been saying for years.

He suggests that initially a critical tool post-2008 crisis, stress tests now need more dynamism to adapt to emerging risks. Tarullo now proposes decoupling stress tests from capital requirements, allowing them to serve purely as a supervisory tool. This, he believes, would reduce institutional inertia and enhance the flexibility of stress tests, making them more effective in anticipating and mitigating future financial shocks.

Now, as an attempt to be fair, Gov. Tarullo had to play something of a political game along the way that many of us could easily ignore. If one were to trace his evolution, one might characterize five phases of his position:

2009-2010: Advocacy for rigorous, post-GFC stress tests.

2011-2013: Focus on refining stress testing models and transparency.

2014-2016: Addressing criticisms, advocating for more dynamic and diverse scenarios.

2017-2019: Reflection on stress testing's successes and limitations, pushing for continuous evolution.

2024: Reconsideration of stress testing's regulatory uses, proposing significant changes to enhance its dynamism and effectiveness.

Now I think most of us would agree that the 2009-2010 approach was necessary for restoring trust in the banking system, the banking system needed more capital and this was a reasonable way of determining the level, and the 2011-2013 approach was at least directionally correct if one were going to have the regime. It is the post-2014 world where there were diminishing marginal returns to the supervisory stress testing regime, and one could argue that the diversion of resources towards the regulatory scenarios was harmful. He did acknowledge in the 2018 period that there was the risk they had become too predictable.

I would highlight two particular quotes from his paper:

The first of the realistic options would decouple the annual stress test from the determination of minimum capital requirements. Annual stress testing would become a supervisory exercise designed to elicit information about risks faced by individual banks and by the banking system as a whole.

To compensate for the decline in actual capital requirements that would result from this decoupling, point-in-time capital requirements would be increased. Although the results of stress tests would no longer be the presumptive basis for setting minimum capital levels, they could still be used by supervisors as an input in deciding whether to direct specific banks to increase their capital ratios and to inform changes in generally applicable capital requirements."

For the positive, this would lessen the role of the supervisory process in setting PUBLICLY-DISCLOSED capital levels for each institution, and would provide MARGINALLY more latitude for banks to set their own capital targets.

I say marginally for two reasons. The first is that target rating agency rating requirements may be the binding constraint, and second, because the stress test is really just a way to put a sufficient capital buffer in place to insure that regulatory minimums will not be breached. Any lowering of the amount of total capital below the sum of minimum requirements and a capital buffer able to absorb significant stress is a defacto increase in the probability the firm will breach the threshold. As I have stated in prior PoRs, the regulatory minimum represents something of a proxy for the need of the sovereign to intervene, and the buffer is the firm’s decision on what probability of this distress they are willing to bear.

Anyway, I think Tarullo’s conversion is a good development, and perhaps when combined with an agreement on the Basel 3 Endgame we may be able to revert to more proper risk management rather than regulatory compliance.

Corporate Credit

Sometimes the best papers just document what we all understood to be happening. In The Changing Landscape of Corporate Credit (Liberty Street), NY Fed economists Boyarchenko and Elias do just that, providing a nice overview of changes in intermediated and bond credit over the last few decades:

… we investigate how the composition of debt instruments on U.S. firms’ balance sheets has evolved over the last twenty years.

… the share of intermediated credit has increased over time.

[However] for firms that have both loans and bonds outstanding at a given point in time, the share of intermediated credit has declined by approximately 8 percent over the last twenty years.

… the share of intermediated credit for the top 25th percentile of firms has stayed relatively constant (at around 30 percent), the share of loans has decreased considerably for the rest of the firms (from around 60 percent to 50 percent). That is, smaller firms that have access to both bond and loan markets are increasingly relying more on bond financing.

… the weighted-average maturity of corporate bonds outstanding has decreased almost monotonically over the last twenty years, from about eleven years in 2002 to slightly lower than 8.5 years in 2022.

In contrast, while the average maturities of bank loans were increasing prior to the global financial crisis (GFC), peaking at more than six years average maturity in the 2009–11 period, they have sharply decreased since then, reaching an average maturity of four years in 2022.

Intermediation Chains & Leverage

Leverage finds a way: a comparison of US Treasury basis trading and the LDI event (Bank Underground)

This post explores the similarities and differences between the activity of asset managers and hedge funds in US Treasury (UST) futures markets, and the relationship between liability-driven investment (LDI) funds and lenders in the gilt repo market.

LDI strategies and the UST basis trade both represent an intermediation chain that link asset managers’ demand for leveraged long-term interest rate exposure on one side to a demand for short-term safe assets by investors such as MMFs on the other side, with dealer banks sitting between them.

This is a moderately interesting paper that outlines differences in the way leveraged asset managers in the US and UK used sovereign bond leverage. There is a bit of apples-to-oranges in the paper as they are comparing UK insurers with US asset managers. They attempt to make the case that the difference between the US and the UK is the US presence of hedge funds making the UST basis trade.

Bank Runs

An outstanding and important paper from NY Fed economists Cipriani, Eisenbach, and Kovner Tracing Bank Runs in Real Time (NY Fed)

We use high-frequency interbank payments data to trace deposit flows in March 2023 and identify twenty-two banks that suffered a run — significantly more than the two that failed but fewer than the number that experienced large negative stock returns. The runs were driven by large (institutional) depositors, rather than many small (retail) depositors. While the runs were related to weak fundamentals, we find evidence for the importance of coordination because run banks were disproportionately publicly traded and many banks with similarly bad fundamentals did not suffer a run. Banks that survived a run did so by borrowing new funds and then raising deposit rates — not by selling liquid securities.

We identify 22 run banks with significant negative net outflows on one of the days between March 9 and March 14, all with net liquidity outflows exceeding 5 standard deviations of their historical net outflows.

the new borrowing is consistent with a pecking order where banks prefer borrowing from FHLBs over borrowing from the discount window/

the runs were entirely a wholesale phenomenon

Run banks have worse fundamentals along several dimensions that make them vulnerable to runs. They have significantly lower cash holdings and capital ratios, and rely significantly more on uninsured depositors; they also borrow significantly more from FHLBs. Run banks also have higher unrealized losses on HTM securities, although the difference to non-run banks is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Consistent with perceived too-big-to-fail status …being very large (above $250 billion) is negatively associated with runs: banks smaller than $250 billion are 7 to 15 percentage points more likely to be run.

There is a very good section of the paper subtitled Anatomy of the 2023 runs.

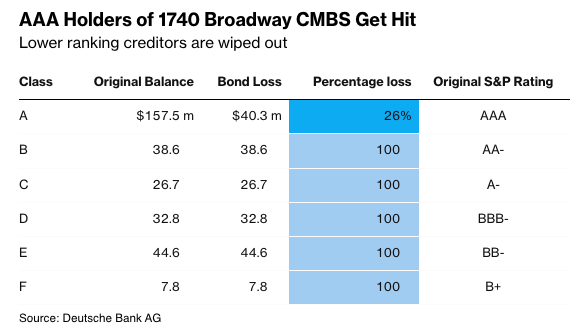

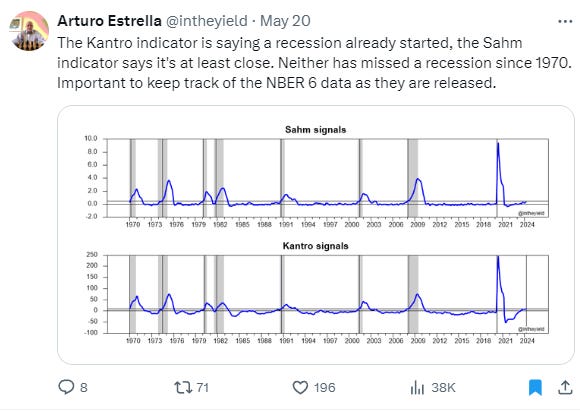

Are We In A Recession?

Majority of Americans wrongly believe US is in recession – and most blame Biden (Guardian)

Just to be clear, the Sahm Rule indicating that we are in a recession, has not triggered.

This NYU Symposium Sounds Interesting

I can’t find an online registration link. If someone shares me a link I will post it in a future PoR.