Perspective on Risk - May 15, 2023 (Druckenmiller & Brunnermeier; Shots Fired)

Fiscal Domination, Financial Domination, Monetary Policy; Bowman on Banking; 2008 Fed After-Action Review; European Bank Supervision; Did Credit Suisse Default or Not?

Fiscal Domination, Financial Domination, Monetary Policy

This topic will interest at least three of you; it should interest you all.

Concerns about fiscal dominance are back on the table following remarks by Stan Druckenmiller at the Ira Sohn conference. I’m sure many of you have seen them. Perhaps more important are his remarks at USC preceding this event. The text of his remarks is here, and his slides are appended to the end of the remarks. They comment of the same themes, but are more coherently organized.

During the last decade, our debt grew from $15T to $31T today… a level of indebtment only comparable to that after WWII. But what is worse is that this debt does not account for what the government has promised it will pay you in terms of social security and Medicare. It actually assumes these payments will be ZERO.

The arithmetic for your “entitlements” just doesn’t work. Imagine asking yourself how much taxes need to be raised today to maintain the current magnitude of safety nets into the future. Economists call this a “fiscal gap” measure. Today that measure is 7.7% of GDP, up from 7.2% when I presented here 10 years ago. This is equivalent to a 40% increase in all Federal taxes collected, or, an immediate and permanent cut of 35% in federal spending.

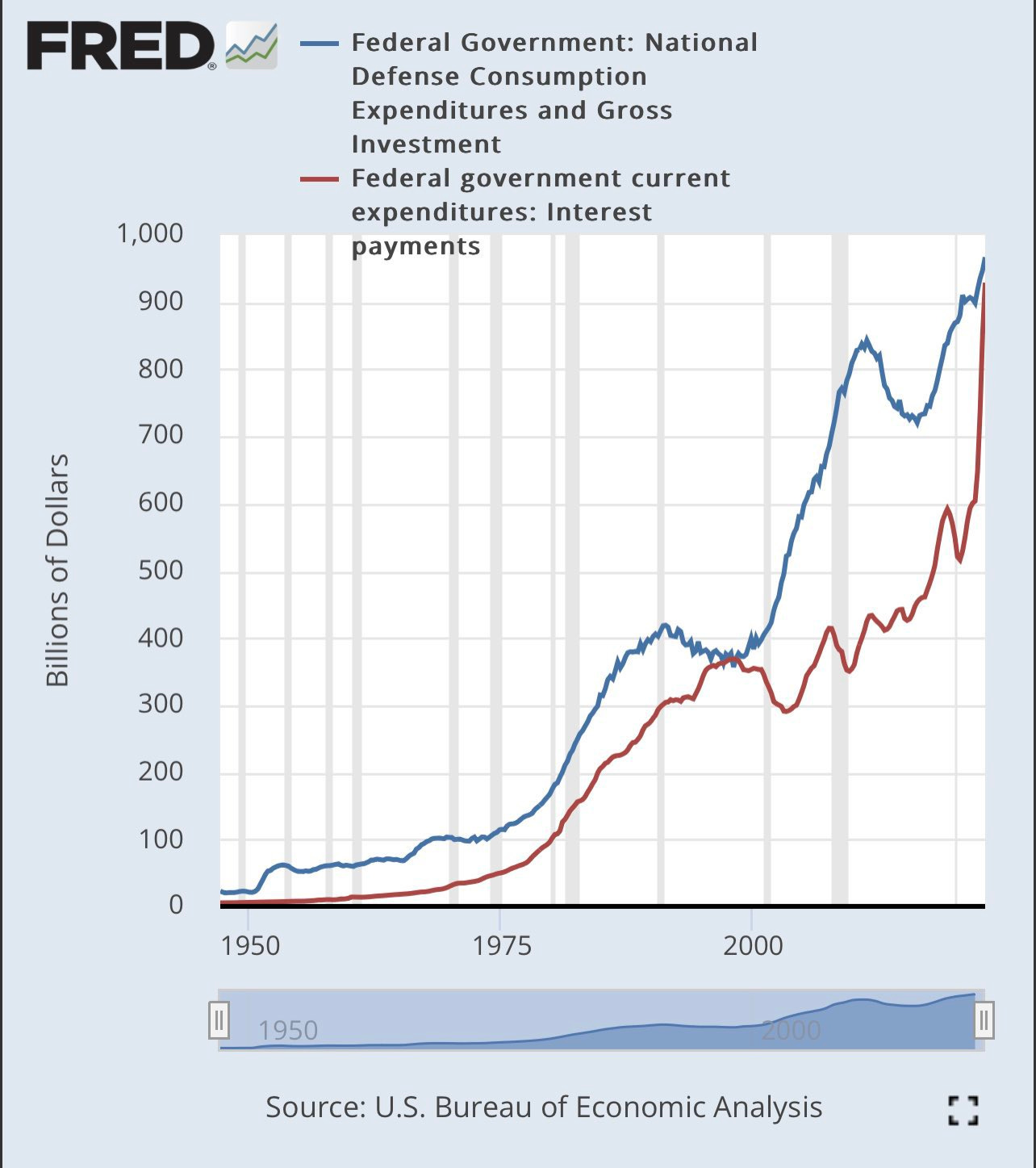

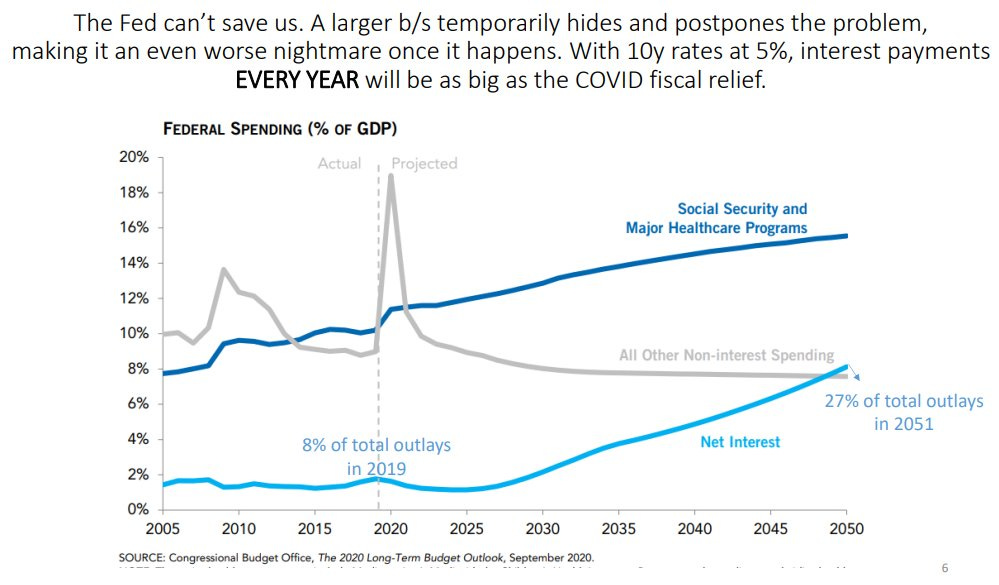

To give you a sense of how bad it could get, with interest rates at 5%, interest payments every year would be as big as the entire covid relief of 2020. As the charts shows, interest payments go from 8% of outlays to 27% by 2050. This is a nightmare for future economic growth, investment and productivity, and, of course you, the future taxpayer.

To put it another way, debt service is now equivalent to defense spending.

As if the irresponsible fiscal behavior wasn’t enough, around 15 years ago the Fed simultaneously decided to start courting with asset bubbles.

Since then, and despite these confident words and several periods of strong growth with very high inflation, the Fed never felt the need to meaningfully reduce its balance sheet. The balance sheet of the Fed today stands at just below $9T, or 10 times as large as before the financial crisis. I repeat… 10 times

Some of the costs of the Fed’s loose policies are now apparent to all.

Druckenmiller followed up the USC remarks with an interview at the widely followed Ira Sohn conference:

It looks to me like the monetary and the fiscal authorities are kind of at the end of their rope

we come into this with fiscal challenges completely unlike any time we've ever been in this situation before

we basically wasted all our bullets amazingly in the last few years in in an economic expansion um but you know the government can always print money. Try look at look at what they did in Japan I mean they tried everything and it didn't work uh the question is are we there - the answer is I hope not.

I’ve written about ‘financial dominance’ in the context of the bank failures. Druckenmiller touches on them obliquely in his USC remarks when he states:

Trying to correct the biggest mistake in Fed history, in the last year they have now raised rates 500bps. Better late than never, I guess. Still at the first signs of trouble, the Fed last month and in just 4 days, undid most of the small progress they had done in reducing their balance sheet. This asymmetric Fed response is what feeds the lack of serious structural action in DC from both sides of the isle. It allows the Biden administration and Congress to avoid having to address our long‐term dilemmas.

In researching how to write this substack, I came across this Rethinking Monetary Policy in a Changing World (IMF; Brunnermeier), Marcus Brunnermeier is one of the most thoughtful and insightful economists working today. His work is closely followed by central bankers and other policymakers.

Although financial stability remains an important concern, there are important differences between the current environment and the one that followed the global financial crisis:

Public debt is now high, so any interest rate increase to fend off inflation threats makes servicing the debt more expensive—with immediate and large adverse fiscal implications for the government. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis in early 2020, it is also evident that fiscal policy can be a significant driver of inflation.

Instead of deflationary pressures, most countries are experiencing excessive inflation. That means there is now a clear trade-off between a monetary policy that tries to reduce aggregate demand by raising interest rates and one that aims to ensure financial stability.

The nature and frequency of shocks have changed. Historically shocks were mostly from increases or decreases in demand—with the prominent exception of the supply shocks during the so-called stagflation of the 1970s. Now there are many shocks: demand vs. supply, specific risks vs. systemic risks, transitory vs. permanent. It is difficult to identify the true nature of these shocks in time to respond. Central bankers need to be more humble.

The low interest rates and less extreme public debt levels that prevailed after the global crisis permitted central banks to ignore what were then relatively inconsequential interactions between monetary and fiscal policy. The period following the 2008 crisis was one of monetary dominance—that is, central banks could freely set interest rates and pursue their objectives independent of fiscal policy. Central banks proposed that the core problem was not rising prices, but the possibility that weak demand would lead to a major deflation

During the COVID-19 crisis, circumstances changed dramatically. Government spending rose sharply in most developed economies. In the United States, the federal government provided massive and highly concentrated support in the form of “stimulus checks” sent directly to households.

This is pretty much saying the same thing as Druckenmiller, just in academic speak.

The accompanying buildup of public debt raised the possibility of fiscal dominance—in which public deficits do not respond to monetary policy. Whereas low debt levels and the need for stimulus allowed monetary and fiscal authorities to act in tandem following the global financial crisis, the prospect of fiscal dominance now threatens to pit them against one another. Central banks would like to hike interest rates to rein in inflation, whereas governments hate higher interest expenses.

A key question for policy is what determines the winner of any contest between fiscal and monetary dominance. Legal guarantees of central bank independence are insufficient, by themselves, to guarantee monetary dominance: legislatures can threaten to change laws and international treaties can be ignored, which could cause a central bank to hold off its preferred policy.

As Druckenmiller puts it

I think the fed's independence will survive. I will say it'll be the most risk of that Independence that I will have seen in 50 years so it's not a slam dunk. I think there's a five to ten percent chance if the hard lending got really bad and people looked back at the record of the fed the last five or ten years …

Brunnermeier continues:

Central banks face new challenges in the interaction between monetary and financial stability. They now operate in an environment in which private debt is high, risk premiums on financial assets are depressed, price signals are distorted, and the private sector relies heavily on the liquidity the central bank provides in a crisis.

Now, there are clear trade-offs between inflation management and financial stability, because interest rate hikes to fight inflation threaten to destabilize financial markets.

The willingness to maintain large balance sheets has led to a buildup of private debt, depressed credit spreads, distorted price signals, and high house prices from increased mortgage lending. The private sector has come to depend on the liquidity provided by central banks and has grown accustomed to the low-interest-rate environment. Indeed, financial markets have come to expect that central banks will always step in when asset prices fall too low. Because the private sector has become so dependent on the central bank, the contractionary effect of unwinding central bank balance sheets may be significantly more visible than the stimulus provided by QE.

The reliance of the private sector, especially the capital markets, on central bank liquidity has led to a situation of financial dominance, in which monetary policy is restricted by concerns about financial stability.

These problems call for rethinking how monetary policy interacts with financial stability. It is crucial that central banks aim to restore price signals smoothly in private markets in which they have intervened excessively.

Central banks should anticipate this tension and impose greater macroprudential oversight—that is, regulating not only with an eye to the soundness of individual institutions, as has been the aim of financial regulation historically, but also to ensure the soundness of the financial system as a whole. Such enhanced macroprudential regulation should have a particular focus on monitoring dividend payouts and buildup of risk in the nonbank capital markets. Finally, central banks should reconsider their roles as lenders and market makers of last resort and ensure that any interventions are only temporary.

Central banks overlearned the lessons of the 2008 crisis, which caused them to abandon their traditional approach to inflation expectations.

That was a real shot at the Fed

Central banks also took a complacent approach to dealing with supply shocks.

The intellectual framework adopted by central banks after the 2008 crisis does not yet appear to have de-anchored inflation expectations. But it would be costly to wait until de-anchoring begins to alter the framework. Warning signals have already emerged in recent inflation expectations data. The loss of the inflation anchor, with its attendant consumer and business uncertainty, would hinder both aggregate demand and supply.

Policy cannot tighten only after inflation occurs. Instead, central banks should take action as soon as warning signals flash. Central banks must incorporate both households’ and financial markets’ expectations of future inflation, since those expectations shape both aggregate demand conditions and asset prices.

This last bit means higher for longer.

Essentially, this is two ways of saying the same thing, while chastising monetary and fiscal authorities for decisions made during Covid.

So what does all of this imply?

On the fiscal side, get the house in order to reduce the outstanding debt. This likely means both tax hikes and spending restrictions, particularly on entitlements.

On supervision, more aggressive supervision to make sure the system continues to function appropriately. Figure out how to get capital into the banks that need it (or get the losses out through failure, which is a 2nd best solution).

Monetary policy: without (1) and (2) there is a risk that monetary policy will not be able to be aggressive enough to excise inflation. The argument is that rates need to rise despite the risk to the financial system and the cost to the national debt. Will Powell cave during an election year?

And yes, I do expect to hear from a number of you on this post.

Shots Fired? Fed’s Bowman on Banking & Supervision

Important speech by Fed Gov. Michelle Bowman: The Evolving Nature of Banking, Bank Culture, and Bank Runs (Fed)

Shots fired. Randy Quarles wont be happy

In practice, the "maintenance" of the bank regulatory and supervisory framework has often been challenging, in part because maintenance requires vigilance in responding to evolving circumstances and risks. Lapses in this effort are revealed when something breaks, which could include fragilities resulting from the emergence of unidentified risks and financial stability threats; banking practices that expose shortcomings in the supervisory framework; or policymakers, regulators, and/or examiners who have lost sight of the fundamental goal of encouraging prudent banking practices and appropriate risk management.

The need for maintenance of the U.S. bank regulatory and supervisory framework has come into stark relief with the failures of two large banks in March, followed by a third at the beginning of May.

Then we get some wise framing. Recognizes that banks are only part of the financial system, and that risk can move out of the regulated banking system, in which case it usually shows back up as counterparty risk.

The future and current policy choices made in responding to these failures will have important consequences for the U.S. banking system. Including the extent to which bank regulation will continue to drive banking activities from regulated banks and into shadow banks. While shoring up the resiliency of the banking sector is important, it is also important that we consider the consequences of any regulatory change.

Given the recent banking sector stress, it is clear that we need to review the bank regulatory and supervisory framework to determine whether updates are needed. As we consider potential changes to improve supervision and regulation, we should start from a baseline understanding of the available tools and determine whether those tools have been utilized and implemented effectively. Before regulators seek new tools, it is necessary to understand the need—how would the use of those new tools address deficiencies in the existing regulatory toolkit? Imposing additional requirements on regulated institutions without understanding this need results in additional costs and can have unintended consequences like encouraging bank consolidation and constraining credit availability to critical business activities or geographies. In addition to these unintended consequences, we also need to carefully consider the broader implications of regulatory change for financial stability.

Diving into supervision, she suggests that there will be more formal supervisory actions. However, the focus is yet again on process. Implicitly, supervision is about process while regulation is about constraining risk; I don’t like this.

Starting with supervision, effective bank supervision requires both transparency in expectations, and an assertive supervisory approach when firms fail to meet these expectations.

Part of the solution to inaction may simply be to take a stronger approach when examiners have identified deficiencies in need of remediation. But for some banks, management's responsiveness to supervision—traditionally an area that rewarded conservative and prudent management—has changed, with a greater emphasis on innovation, especially those that promise to transform the business of banking.

These shifts impact supervision, in that we need to reevaluate the effectiveness of formal and informal enforcement mechanisms. If moral suasion as an informal tool is less effective, and bank management and boards are less attuned to hear and respond to supervisory messages, we need to reconsider our supervisory toolkit. This may mean taking more formal remediation measures, with definitive timelines, and imposing meaningful consequences for firms that fail to remediate issues in a timely way.

Doesn’t seem a fan of increased regulation. As discussed in the last Perspective, some like Amati are lobbying for materially higher capital requirements. My reading of this section suggests he may be pushing back even on extending the LCR to a broader set of banks.

In response to the recent bank failures, it is tempting to engage in a wholesale revision of the bank regulatory framework. Before changing rules, we need to take a critical look at actual weaknesses, and acknowledge the strengths that should be preserved.

Overall, our regulatory framework is also strong. This framework has materially increased bank capital and liquidity and added a number of other requirements to improve resiliency, including new stress testing and resolution planning requirements.

We should be careful and intentional about any significant changes to the regulatory framework, including imposing new requirements that will materially increase funding costs, like higher capital requirements or the requirement of firms to issue long-term debt. Many of the issues related to the recent bank failures have been identified in bank management and supervision. Therefore, a broad-based imposition of new capital requirements on all banks with more than $50 billion in assets would be a far more costly solution than taking the time to specifically identify and address known management and supervisory process issues.

Going forward:

First, I believe that the Federal Reserve should engage an independent third party to prepare a report to supplement the limited internal review to fully understand the failure of SVB. This would be a logical next step in holding ourselves accountable and would help to eliminate the doubts that may naturally accompany any self-assessment prepared and reviewed by a single member of the Board of Governors.

Wow. That is clearly a shot at Barr.

Second, I believe we need to do a better job identifying the most salient issues and moving quickly to remediate them. It is clearly evident that both supervisors and bank management neglected key, long-standing risk factors that should be an area of focus in any examination. These include concentration risk, liquidity risk, and interest rate risk. We have the tools to address these issues, but we need to ensure that examiners focus on these core risks and are not distracted by novel activity or concepts.

A call for a more aggressive supervisory approach. What was missed was 1) the risk introduced by SVB’s rapid growth, and 2) funding reliance on ‘hot’ money.

Finally, we should consider whether there are necessary—and targeted—adjustments we should make to banking regulation. This will likely include a broad range of topics, including taking a close look at deposit insurance reform, the treatment of uninsured deposits, and a reconsideration of current deposit insurance limits. We should avoid using these bank failures as a pretext to push for other, unrelated changes to banking regulation.

That is preemptive pushback on the Warren crowd.

I have heard the drumbeat calling for broad, fundamental reforms for the past several years, shifting away from tailoring and risk-based supervision. I believe this is the wrong direction for any conversation about banking reform. The unique nature and business models of the banks that recently failed, in my view, do not justify imposing new, overly complex regulatory and supervisory expectations on a broad range of banks. If we allow this to occur, we will end up with a system of significantly fewer banks serving significantly fewer customers.

Gotta say I like this. She gets it. She is aware of both Chesterton’s fence and the Law of Unintended Consequences.

The other thing I’d note about the speech is that it discussed the failures as idiosyncratic. The word ‘systemic’ never appears in the speech. I would prefer that, rather than focusing on how to supervise non-systemic banks better, it focused instead on identifying systemic risks and left the supervision of non-systemic firms to the FDIC and States.

… three U.S. banks with unique risk profiles

The unique nature and business models of the banks …

And as for the timing of any new regulations, most of you know my mantra: “take the over.”

2008 Fed After-Action Review

Following the GFC, the NY Fed commissioned Report on Systemic Risk and Bank Supervision from David Beim of Columbia Business School on possible learnings from what worked and what did not in supervision prior to the crisis. I didn’t agree with all of their findings; I felt that some of the participants had a bit of a conflict of interest in advancing their findings. Regardless, it is an interesting historical document, and there is a link to it in footnote 169 of the Barr report.

I was struck by reviewing the Beim Reports eleven major recommendations. Here they are:

Here is a summary of our recommendations:

Foundational Matters

Adopt financial stability as a central mission, on a par with price stability.

Build the intellectual and political case for systemic risk regulation.

Organizational Matters

Establish a new senior position of Systemic Risk Advocate and dedicate resources from various areas of the bank in support of this position.

Establish a process for collecting and analyzing cross-firm exposures to identify financial market vulnerabilities that could affect a broad range of institutions and markets.

Cultural Matters

Launch a sustained effort to overcome excessive risk-aversion and get people to speak up when they have concerns, disagreements or useful ideas.

Give more resources to the Relationship Managers and demand from them a more distanced, high-level and skeptical view of how their bank tries to make money and what distinctive risks this entails.

Refocus Risk Management away from studying banks' systems and toward developing standardized approaches to assessing risk itself. Strive for a better understanding of the aggregate level and trends in bank risk.

Re-think risk-focused supervision to increase the emphasis on independent identification and examination of actual risks at banks compared to risk-control reviews

Improve the interaction between Relationship Management and Risk Management by providing them with customized training in executive communications and conflict management.

Communication Matters

Announce that improved communication across organizational lines is a centrally important need for recognizing and understanding emerging systemic issues and institute practices that encourage it.

Remember and repeat the factors in successful regulatory initiatives. Articulate the personal qualities and behaviors wanted in supervisors, repeat them frequently and use them in both hiring and personnel reviews.

If I think about the current spate of bank failures with list list in mind, recognizing that these findings did not get automatically implemented as written, I have the following observations:

Certainly point 1 has not fully been embraced, not that it necessarily should. The Fed has tailored its supervision, with more aggressive supervision of firms designated as systemically-significant.

Point 4 touches on systemic risk when it states “identify financial market vulnerabilities.” If we accept that there was systemic risk in the failure of SVB and its potential to provoke a run that has systemic consequences, then the Fed missed it. It’s not clear, however, that they lacked the necessary information.

I’m not going to kill the examiners for points 4 & 5; excessive risk-aversion and “a more distanced, high-level and skeptical view of … their bank…” The examiners did highlight the liquidity issue once the responsibility was moved to the LFBO group.

Points #7 and #8 are probably the big misses. All of the communication seemed to focus on process and MIT rather than an independent assessment of the risk.

Refocus Risk Management away from studying banks' systems and toward developing standardized approaches to assessing risk itself. Strive for a better understanding of the aggregate level and trends in bank risk.

Re-think risk-focused supervision to increase the emphasis on independent identification and examination of actual risks at banks compared to risk-control reviews

The one thing we do know about Fed culture is that it is very self-critical and will focus intently on “lessons learned.” My main concern is that the Fed course-corrects away from systemic-risk supervision with an increased emphasis on smaller, non-systemic banks.

European Bank Supervision (of Credit)

The European Court of Auditors issued EU supervision of banks’ credit risk.

We decided to carry out this audit where we assessed whether the ECB’s approach to supervision of credit risks in banks and in addressing legacy non-performing loans (classified as such before April 2018) was operationally efficient. Our focus was on the ECB’s action in the 2021 supervisory cycle, including a sample of 10 banks with identified challenges with non-performing loans.

Our overall conclusion is that the ECB stepped up its efforts in supervising banks’ credit risk, and in particular non-performing loans. However, more needs to be done for the ECB to gain increased assurance that credit risk is properly managed and covered.

The methodology, newly applied in 2021, for determining the additional capital requirements (pillar 2) to be imposed by the ECB as supervisory authority did not provide assurance that the banks’ various individual risks were appropriately covered. Moreover, the ECB did not apply its methodology consistently: it did not impose proportionally higher pillar 2 requirements the higher the risks faced by a bank.

The ECB also did not escalate its supervisory measures for some banks even in the presence of high and sustained credit risk and persistent control weaknesses. The supervisory cycle in 2021 took very long (13 months). The final decisions were not issued to banks until February 2022, mainly due to a lengthy dialogue and approval phase. Such a long duration implies a risk that ECB’s assessments do not reflect banks’ actual risk profiles

Lastly, supervision suffered to some extent from the fact that several national supervisors fell short of their commitments to provide staff resources.

Did Credit Suisse Default or Not?

Some people hedge with credit default swaps. Some speculate. The CDS pay out when a firm defaults. So did Credit Suisse default?

FT Alphaville noticed developments with Credit Suisse CDS at ISDA ISDA* happening!

This week, someone finally asked the determinations committees — a group of up to 10 representatives from banks and five from investment groups that decides whether credit-default swaps pay out — whether CS defaulted.

There was about $20bn of CDS on CS debt at the time of its collapse, and, as Risk reported at the time, it wasn’t “crystal clear” whether the AT1 bond vaporisation would trigger CDS payouts. But it seems some hedge funds have grown confident that it will.

Be careful how you reduce risk. Sometimes a hedge is just a banana.