Perspective on Risk - May 10, 2023

Details of the Supervision of SVB; Funding the Banks; Sinners repent; or be scourged; A Primer on Unrealized Losses; Fed’s Latest Financial Stability Report; The Right To Make A Terrible Decision

I do at times feel like I am spamming you, and I do have other topics in the hopper (a nice post on GPT-4), but the banking developments keep coming pretty quickly.

Details of the Supervision of SVB

Wow!

The California Department of Financial Protection has released eight target exam letters, thirteen supervisory reports, and four supervisory actions relating to their joint (with the Fed) supervision of SVB: Review of DFPI Oversight and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. This degree of release is unprecedented. Sneaky too; not released by the Fed, although the Fed had to agree to the release.

Target Letters

The first letter reviewing Global Risk Management in 2019 is classic old-school Fed supervisory-speak. Note how long it takes to get to the meat (I bolded that part).

SVBFG’s board has established a risk committee and the organization’s risk-management program complies with the broad requirements of Regulation YY. Additionally, management continues to develop and implement a risk management framework as the organization grows in size and complexity; however, further enhancements are needed to ensure the effective implementation of an appropriate internal controls and risk oversight structure. While the second LoD has made notable progress and provides sufficient oversight of risk-taking activities, aggregate risks, and concentrations to ensure compliance with the board-approved risk appetite, concerns persist about certain aspects of the structure, independence, and functional expertise within the risk-management framework. The most notable concerns surround the reporting line of the CCO, information technology expertise, and second LoD independence when participating in risk-taking activities. SVBFG has made reasonable progress remediating MRAs within the scope of this inspection; we are closing all three, but recasting two to reflect the remaining work needed to address the underlying supervisory concerns

After this, however, the communication got MUCH better.

The 2022 Global Risk Management target letter is much more direct.

The Firm's governance and risk management practices are below supervisory expectations. The board has not provided effective oversight to ensure senior management implements risk management practices commensurate with the Firm’s size and complexity. The board did not provide effective oversight of management’s responsibility to implement the large financial institution (LFI) readiness initiatives or the foundational risk management program principles applicable for all banks, irrespective of size. When risk management weaknesses were indicated by breaches of internal risk metrics, internal audits and past regulatory examinations, the board did not hold senior management accountable to remediate these issues.

Board oversight does not meet supervisory expectations.

The Firm’s risk management practices are not effective.

The internal audit target very bluntly stated

SVBFG/SVB’s Internal Audit (IA) is not fully effective. The overall assessment was driven by material weaknesses in the risk assessment process, the process to define the IA audit universe, IA’s continuous monitoring, and audit execution.

The liquidity risk management letter gets directly to the point and even gets some of the specifics precisely correct:

The firm’s liquidity risk management practices are below supervisory expectations set forth in applicable guidance. The FR identified foundational shortcomings in three key areas: (1) internal liquidity stress testing (ILST), (2) the liquidity limits framework, and (3) the contingency funding plan (CFP).

But again, what was missed was an adequate assessment of the absolute level of the risk. The level of the risk was addressed strictly through the (accurate) process comments:

Key assumptions rely on incomparable peer benchmarks. SVBFG’s historical analysis was based off other banks largely with a retail deposit base subject to FDIC insurance coverage, while SVBFG’s deposit base is largely commercial deposits without FDIC insurance coverage.

The current stress scenario does not sufficiently stress SVBFG’s liquidity exposures. Without sufficiently designed assumptions and scenarios, the firm’s liquidity buffer under stress may be insufficient.

The firm’s current limit framework is inadequate for the purpose of measuring, monitoring, and controlling risks. These inadequacies may underestimate the demands on available liquidity sources in stress.

Exam Reports/Annual Rollups

Interest rate risk was not addressed through a target exam, and had scant mention in the annual reports before the November 2022 letter that conveys the joint CAMELS rating.

The issue of interest rate risk is addressed up front in that letter, however the letter is not written in a way that conveys the risk of unrealized losses on the securities portfolio and to capital. In fact, the comment strictly conveys concerns about the effect of poor modeling on estimates of net interest income. The language is truly regrettable: “confirmed asset sensitivity and the firm benefiting from rising rates.”

The Firm's interest rate risk (IRR) simulations are not reliable and require improvements. SVB’s balance sheet had been modeled and reported as asset sensitive. While data from the first 3 quarters of 2022 confirmed asset sensitivity and the firm benefiting from rising rates, management is forecasting meaningful Net Interest Margin (NIM) compression, Net Interest Income (NII) decline and significant adverse earnings impact starting in 4Q and into 2023. Changes in NIM, NII and earnings are directionally inconsistent with internal projections and IRR simulations, calling into question the reliability of IRR modeling and the effectiveness of risk management practices. Unreliable IRR modeling directly impairs management and the board’s ability to make sound asset liability management decisions.

Another issue that I have is that none of the supervisory documents address directly the elephant in the room: the extremely rapid growth of the bank. It is obliquely addressed on page 4 of the 2020 rollup:

With an expectation of continued rapid growth regarding size, complexity, and global presence, a near term focus on acquisition integration must be a priority as other strategic projects are considered.

The only real reference is about the effect of the growth on which supervisory portfolio was handling the bank.

We delayed issuing the ratings for the 2021 supervisory cycle to account for the full onset of large bank supervisory expectations and to better assess the thematic root causes associated with the previously cited supervisory findings.

Funding the Banks

The $64 question coming out of the SVB debacle is how to think about bank funding going forward. The scale and speed of the deposit run far exceeded what we have seen historically, and is far in excess of what they system was designed to accomodate.

Silicon Valley Bank, for example, lost $42bn, or a quarter of its entire deposit book, in a single day.

From the latest Fed Financial Stability Report (discussed later):

Frances Coppola has a nice primer on liquidity in her latest substack Bank failures: it's all about liquidity.

The job of banks is to make illiquid things liquid. When a bank lends, it creates new liquidity for the borrower, accepting in return an illiquid asset such as real estate or an intangible asset such as a credit score. This process of making illiquid things liquid is what we mean when we say “banks create deposits when they lend”.

The deposit created as a result of lending is real money as far as the borrower is concerned: it can be drawn in the form of banknotes, transferred to another account, or paid out in return for goods and services. It is indistinguishable from money the borrower deposits in their account.

But as far as the bank is concerned, deposits are merely an accounting record, not a means of settlement. Banks create deposits, but they can’t create the liquidity needed to enable those deposits to be drawn. So when a bank whose liabilities consist mainly of deposits withdrawable on demand suffers a bank run, it can literally run out of money. Its ability to “create money” doesn’t help it. It can’t bootstrap its own liquidity.

We’ve discussed SVB’s liquidity management weaknesses before; high-levels of uninsured deposits all ran in a coordinated way over two days. Why couldn’t SVB just borrow from the FHLB system or the Fed’s discount window?

The first problem was that SBNY’s management didn’t know how much money it needed. And the second was that although the bank had plenty of illiquid assets, they either weren’t of sufficiently good quality or their value was unknown. Or they were already encumbered. The NY DFS says that the bank’s attempt to obtain funding from the NY Fed’s discount window was seriously hampered by the fact that it had already pledged much of its good-quality collateral to the FHLB

The problem in both cases was insufficient information about the collateral. Like a traditional pawnbroker, the amount the Fed will lend through its discount window depends on the quality of the collateral: the poorer the quality, the smaller the amount the Fed will lend. But evaluating the quality of loans and securities is nowhere near as simple as weighing jewellery and biting coins. It means estimating credit and market risks. This takes time and needs accurate information.

Most discount window borrowing involves collateral the Fed already knows about and has had time to evaluate - this is known as “pre-positioning.” But SBNY hadn’t bothered to pre-position collateral at the NY Fed. So it was asking the NY Fed to accept as collateral a package of CRE loans about which it knew nothing. No pawnbroker will lend against collateral that could be worthless or already claimed by someone else. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the NY Fed told SBNY it wouldn’t accept the CRE loans as collateral for discount window borrowing for Monday morning.

This, unlike the subsequent decision by he Fed to create a funding facility that would fund for term securities at their face, rather than market, value is classic central banking. Bagehot 101:

Lend freely, at a penalty rate, against good collateral.

So part of the problem comes down to the need to create information on collateral before you need to borrow. Creating information takes time.

According to this FT article, Former BoE deputy calls for radical overhaul of bank funding, Paul Tucker, the former Bank of England deputy governor

has called for a radical overhaul of how banks are funded so they could withstand a 100 per cent deposit run without following Silicon Valley Bank, Credit Suisse, Signature Bank and First Republic into finance’s graveyard.

The collateral would take the form of high-quality government bonds, portfolios of loans or other assets accepted by central banks, who would assess the collateral’s value daily, and ask for more if the assets’ value had fallen too far.

Tucker said the proposals would not necessarily result in lower lending over an economic cycle,

So Tucker is proposing to solve the problem primarily by prepositioning unencumbered externally-rated collateral at the central bank discount windows. This solves the information problem, but at the expense of decreasing the quantity and increasing the cost of credit to the real economy.

One could modify this to require banks to pre-position loan a certain minimum quantity of collateral at the discount window. This would require a massive increase in staffing and expenditure on the part of the central banks to evaluate the collateral, but would not affect the provision of credit to the extent of Tucker’s proposal.

A different idea would be to require banks to purchase liquidity puts from the central bank sufficient to cover their uninsured deposits. Most central bank research and thinking is about how to handle an institution that is already having an acute funding liquidity shortage. In this case, time is compressed, and the central bank is making a hurried lending decision without the benefit of portfolio effects. Requiring ex-ante purchase of liquidity puts would put the decision into a portfolio context, and relieve some of the time pressures. In theory, the Fed should be able to make an informed decision due to their access to inside information about the banking organization. The cost would presumably be somewhat similar to deposit insurance, but probably priced higher as it reflects uninsured deposits, This would internalize the externality of the Fed funding put.

Sinners Repent

Karen Petrou starts out strong in How to End the Sins of Supervisory Omissions and Bail-Out Commissions:

The reason the FDIC sold First Republic to JPMorgan is that it didn’t want to do yet another resolution that bailed out uninsured depositors. The reason the FDIC didn’t want to backstop more uninsured depositors is that it would have had to say First Republic was as systemic as SVB and Signature Bank and this was nowhere near as credible. The reason the FDIC had to find these two earlier failures systemic was because it couldn’t think of anything better and the reason it couldn’t think of anything better in any of these resolutions is that it was wholly unprepared for them and, now, for any of the others that may come suddenly upon us.

The FDIC must quickly rewrite its resolution playbook, but even a good one won’t work without a new set of triggers for meaningful prompt corrective action that forces change at troubled banks and readies the FDIC for resolution – not bail-out – if change doesn’t come quickly.

And closes strong

The lesson of the last few weeks and especially the last few days is that bank regulators have been living in a cocoon of capital ratios, one into which they will softly settle again if they raise all the capital ratios Mr. Barr’s report also targets. Neither his report nor the FDIC’s mentions what will be done about most of the other risks each agency spots beyond a few promised internal personnel and operational improvements. Worse, nothing is said about resolution beyond a repeat call by Mr. Barr for new long-term debt rules for large regional banks. These new rules will be a waste of time and money if the Fed, OCC, and FDIC do not first ensure that resolutions are unlikely because supervisors step in fast and the FDIC is alerted immediately when a PCA trigger is breached so it can ensure living-will or other resolution plans are credible and operational. Without sound PCA, banks will linger on life support; without resolution, they’ll come out of their decline via bail-out. Been there, done that, let’s not.

Ms. Petrou has an agenda, but she’s not wrong and its a fun read.

Sinners Must Be Scourged

So the authors of Credit Suisse: Too big to manage, too big to resolve, or simply too big?, Anat Admati, Martin Hellwig and Richard Portes are probably on the opposite side from Ms. Petrou. But they too have written an excellent analysis:

Calls to expand government guarantees are misguided. The breakdowns of SVB and Credit Suisse had little to do with the kind of fragility that Diamond and Dybvig (1983) studied in the research recognised by the Nobel Committee. In the Diamond-Dybvig analysis, runs are due entirely to depositors’ self-confirming prophecies about each other. Information about the value of the banks’ assets and their other liabilities plays no role. 3 By contrast, the runs on SVB and Credit Suisse were triggered by announcements that alerted depositors and other investors to deeper problems affecting the solvency of the banks. The failures of bank executives and supervisors to address these problems must be the starting point for any policy discussion.

Swiss authorities actions “raise several questions.”

First, why did the authorities avoid using the vaunted resolution procedures that had been introduced after 2008? … Why was total loss absorbing capacity not used?

Second, did the authorities believe that Credit Suisse was solvent? If they believed that the bank was suffering from only a pure liquidity problem, why was the initial liquidity support from the central bank so limited? And why did the authorities end up taking so many measures that could be justified only if there were serious solvency concerns. … If the authorities doubted the bank’s solvency, why did the Swiss National Bank try to stop the run by a supposedly reassuring statement on 15 March, combined with an announcement of limited support?

Existing arrangements for resolving systemic institutions without disruptions and without bailouts have several fatal weaknesses.

First, there is no satisfactory mechanism to prevent fragmentation along jurisdictional lines once a resolution or bankruptcy procedure is triggered.

Second, existing rules seldom provide for funding a bank while the resolution procedure is implemented.

Third, in many jurisdictions legal provisions about fiscal backstops are unclear.

Finally, the authorities may not have the institutional and human resources needed for handling bank resolution.

Petrou doesn’t want capital standards raised; Admati et. al. do. But the issue now is the speed with which liquidity can run.

A Primer on Unrealized Losses

Economists at the FRB-KC put out a nice primer on unrealized losses and their effects: The Implications of Unrealized Losses for Banks. They have some nice observations, some many of us already know, and a few empirical observations post the Covid downturn. This is a nice simple story your grandmother can understand.

Unrealized losses can influence bank behaviors due in part to the way banks report securities on their financial statements.

Bank balance sheets changed dramatically during the COVID-19

pandemic, making banks more vulnerable to rising interest rates.

Borrowers quickly increased their precautionary cash holdings by drawing down existing lines of credit, thereby increasing loan growth. As the economy recovered, however, loan growth began to decline as firms and households, flush with cash, demanded fewer loans. Facing higher deposits and a dearth of safe investment options, banks began to rapidly accumulate securities.

In addition to simply acquiring more securities, banks also purchased longer-maturity securities during the pandemic.

Larger shares of longer-maturity securities substantially increased

duration risk for banks.

Banks have … classified more securities as HTM [relative to AFS].

Notably, unrealized losses on HTM securities are larger than those

on AFS securities, suggesting banks are strategically protecting their [regulatory]

capital levels by increasing the relative level of HTM securities

Unrealized losses have increased substantially since the pandemic

due to both the sharp increase in interest rates and an increase in duration risk at banks.

Declines in securities prices lower total firm value, and market equity prices typically decline in turn. Lower valuations also reduce bank liquidity by reducing

the amount of cash that can be raised in a sale or reducing the amount of collateral that can be pledged in a repo transaction. This makes the bank riskier, all else equal, and should raise the cost of equity

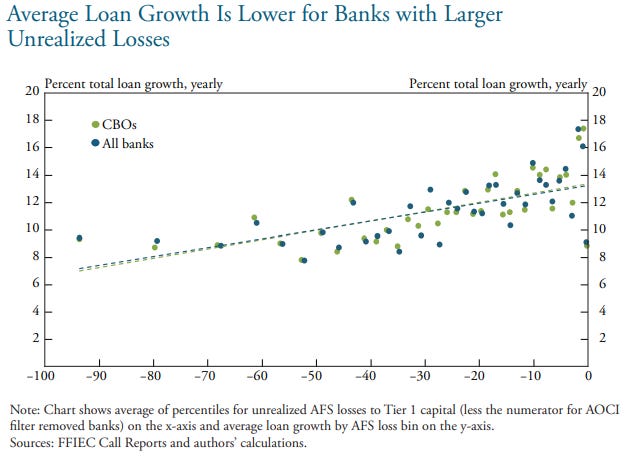

Across all banks, the share of unrealized losses is correlated with slower loan growth, suggesting that banks with fewer unrealized losses expanded loan growth more than their peers with more unrealized losses.

Fed’s Latest Financial Stability Report

Financial Stability Report - May 2023

There’s not much in here that you are not already likely aware.

Selections from the overview:

Risk premiums in equity and corporate bond markets continued to be near the middle of their historical distributions.

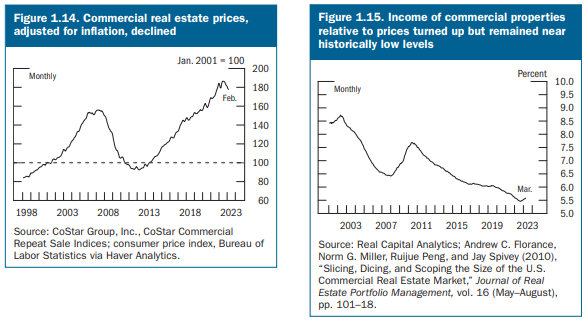

Real estate valuations remained very elevated even though activity weakened. Both house prices and commercial property prices have shown recent declines.

The ratio of total private debt to gross domestic product (GDP) edged down but was still at a moderate level. The business debt-to-GDP ratio remained at a high level, but debt issuance by the riskiest companies slowed markedly. Interest coverage ratios for publicly traded firms declined a bit from historically high levels. Household debt remained at modest levels relative to GDP and was concentrated among prime-rated borrowers.

Broker-dealer leverage rested near historically low levels. Hedge fund leverage remained elevated. Bank lending to nonbank financial institutions stabilized at high levels.

Structural vulnerabilities persisted at money market funds, other cash-management vehicles, and stablecoins. Certain types of mutual funds continued to be susceptible to large redemptions.

Liquidity risks for life insurers remained elevated as the share of illiquid and risky assets continued to edge up

Near-Term Risks to the Financial System

Ongoing stresses in the banking system could lead to a broader contraction in credit, resulting in a marked slowdown in economic activity

Further rate increases in the U.S. and other advanced economies could pose risks

A worsening of global geopolitical tensions could lead to commodity price inflation and broad adverse spillovers

The Right To Make A Terrible Decision

Love this court decision from Delaware

Thank you for the time and thought you put into these notes! They’re always dense (in a positive way, like Ben and Jerry’s ice cream) and informative.