Perspective on Risk - March 4, 2025

More on Delaware Law; Insurance & Private Credit; Hedge Fund Leverage; Prime Brokerage

More on Delaware Law

… the mechanisms that enabled the rise of the institutional investor as a counterweight to insider control may be — well, if not completely unravelled, then at least significantly frayed

Kind of funny that I just wrote about Delaware law and the changing power structure of controlling vs minority shareholders when I read this: RIP American shareholder capitalism (FT).

… a series of legal changes at the SEC and in the corporate haven of Delaware could have enormous consequences. … the combination of the two constitute a violent regulatory swing that reallocates power away from shareholders and toward corporate insiders.

Delaware courts began closely scrutinising relationships among board members — including personal and business ties — when evaluating whether insider transactions had been negotiated at arm’s length.

They imposed even greater scrutiny when the transactions involved a controlling shareholder, two trends that culminated in a Delaware court’s bombshell decision to strike down Elon Musk’s $56bn pay package at Tesla. And last year, another Delaware court invalidated a shareholder agreement at Moelis & Co, on the ground that it handed the company’s founder Ken Moelis too many powers that should have remained with the corporation’s board of directors.

Faced with the ire of the venture capital and private equity firms, the Delaware legislature swiftly amended its corporation law to authorise the kind of agreement that had been invalidated in the Moelis case.

If passed as proposed, the new statute will require courts to assume that board members are independent simply if the company designates them as independent under stock exchange listing rules; make it easier for boards to insulate conflicted transactions from judicial scrutiny; sharply curtail the rights of stockholders to access internal corporate information; and define “controlling stockholders” to exclude anyone with less than 1/3 of the company’s voting power.

Meanwhile, at the federal level, the SEC issued a flurry of new guidances limiting shareholder involvement in corporate governance, the most significant of which concerns whether large investors are deemed “active” or “passive.” … The new guidance could thus turn out to be a dagger aimed at the heart of mutual fund influence.

In sum, the mechanisms that enabled the rise of the institutional investor as a counterweight to insider control may be — well, if not completely unravelled, then at least significantly frayed — in the exact moment that Delaware is retrenching as well. The combination could be exceptionally disruptive.

IYKYK

Insurance & Private Credit

A continuing theme from the last few years has been the growth of the private credit market financed, in part, by insurance companies.

The Atlantic had an excellent overview article, From Investment to Savings: When Finance Feeds on Itself.

The rapidly blossoming marriage of private credit and insurance retirement liabilities contorts the economic identity that investment is a function of savings... The result is a circular system wherein retirement savings feed insurance contracts, which fund leveraged private lending, which then loops back to support the insurers' spreads and payouts.

The author argues that financial markets have shifted from their original purpose:

Financial markets, ostensibly the mechanism for allocating capital to productive enterprises, have come to be viewed by investors, policymakers, and the public as vehicles for funding retirement.

This is important - capital raising has shifted from equity-based entrepreneurial ventures to debt-focused strategies. Of course, most of finance is about refinancing/rolling existing debt.

By favoring debt, collateral-based lending, and guaranteed returns, the system may direct less capital to productive equity investments. In this debt-centric paradigm, real economic growth plays a shrinking role in justifying ever-larger pools of investment capital.

The article explains how private equity firms are leveraging insurance assets:

This makes the normally capital-intensive nature of debt origination considerably more efficient. Whereas in the traditional model, a dollar of insurance assets may only generate ten cents of equity to invest, Apollo's model can turn those ten cents of equity into thirty or forty cents of equity by running it through a private equity structure.

How do I put this more simply.

An insurance company that collects $100 in premiums from customers buying annuities must set aside most of that money (say 90% or $90) to be invested in safe, investment-grade assets like government bonds, the remaining portion, or about 10% ($10) in this case can be used for riskier investments with higher returns and is the insurance companies "equity" portion to invest.

Starting with this “sponsored equity” the Apollo’s and Blackrock’s of the world can attract additional outside equity investments into a fund/pool/security structure. This equity pool can then be leveraged up again.

When Apollo or similar firms own the insurance company, they control both the asset and liability sides of the balance sheet, can direct the large pools of premium dollars into their own investment products and thereby earn fees at multiple levels of the investment chain.

The insurance company serves as the foundation of the whole financial ecosystem. It's what enables firms like Apollo to create a self-reinforcing cycle where retirement savings (through annuities) fund insurance liabilities, which then provide capital for private credit investments, which generate returns to support the insurance products.

They’ve quasi-internalized the cycle.

Moodys/Bloomberg has noted that Insurers to Deepen Private Credit Ties, Moody’s Says (Bloomberg).

The ratings firm expects to see more insurers flock to private credit investments, as they continue to search for yield, particularly through asset-based finance opportunities

The volume of managed retail private debt assets is growing at a faster pace than institutional fundraising, Moody’s wrote in its report.

Regulatory Interest Continues To Grow

I’ve written before about how the Bank of England has been focused on the growth of private credit; we now see other regulators getting into the game.

I might have to pay more attention to FRB-Cleveland Pres. Beth Hammack. She’s a debt capital markets veteran from Goldman who has chaired the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee(TBAC).

Trading Places: My New View from Inside the Federal Reserve (FRB-Cleveland)

A couple of financial market developments are on my radar: the considerable growth in private credit and hedge fund leverage …

… private credit is a significant and growing part of investment strategies for both pension funds and life insurers—and several private-credit managers have purchased insurers to provide predictable funding for further investment. It is worth considering what the implications of large losses at pensions and insurers during an economic downturn could be and whether these risks would spill into the broader financial system.

Finally, the banking system itself may not be immune to financial stability risks posed by private credit … Private-credit firms also take on bank risk via synthetic credit-risk transfers … Concerningly, we have heard of banks’ providing leverage on bank credit-risk transfers, a practice which could bring that risk back into the banking sector.

One area to closely watch is whether we are moving into a new leveraged phase for these funds. As the rapid growth in private-credit investments compresses returns, private-credit funds may employ leverage to increase returns and ensure return of capital to investors. Doing so enables fund managers to ask investors for new money for follow-on funds, thus generating additional fee income for the managers. In other cases, leverage may be used to prop up struggling portfolio companies, while payment-in-kind features exacerbate the layered leverage at risky firms.

German Watchdog to Probe If Insurers Grasp Private Credit Risks (Bloomberg)

Germany’s financial regulator plans to ask the country’s insurers if they grasp the risk of investments they have made in direct loans and private credit funds after a search for yield in the previous decade.

Insurers’ management of risks from private debt and other alternative assets will be a special focus of BaFin’s assessment this year of their investment behavior, Mark Branson, who leads the watchdog, told reporters in Frankfurt on Tuesday.

Private equity made up 5.2% of German insurers’ investments in mid 2022 while private credit accounted for 4.1%, compared with a combined 4.7% at the end of 2019, according to findings of a now discontinued BaFin survey.

ECB Warns Bank Lending for Risk Swaps Can Hide Dangers in System (Bloomberg)

The European Central Bank said it will keep a close watch on banks that are providing leverage to credit funds to invest in synthetic risk transfer trades because that could result in “substantial hidden risks being retained in the banking system.”

The ECB didn’t identify any lenders, but the warning comes after Bloomberg reported that Deutsche Bank AG began tightening the terms under which it provides loans for investors such as hedge funds to buy SRTs.

Nomura Holdings Inc., Morgan Stanley, NatWest Group Plc, Banco Santander SA and Standard Chartered Plc, are also some of the most active lenders to investors in SRTs, which are also known as significant risk transfers, Bloomberg has previously reported.

There are a number of aspects for policymakers to watch here. To date, most of the discussion has been about concentration risk - is firm XYZ controlling too much of the risk, and should they be subject to more oversight? There is a bit of, if not exactly regulatory arbitrage then perhaps regulatory avoidance here as the Apollo/Blackrock’s avoid regulatory oversight while directly controlling the investment, and the insurance company has a somewhat restricted degree of fiduciary responsibility.

The bigger issues for me are the possibility of leverage amplification combined with pricing/valuation opacity. It strikes me that the opacity is worse here than it was for subprime securitizations.

I’d also have concerns about the robustness of the execution chain. As we saw with the subprime crisis, there were incentive issues (underwriting vs volume; backup liquidity exposure) and an unclear understanding of some process issues that only became apparent when things started breaking.

The current private credit market is in the same general order of magnitude as the subprime market was at its peak, though still somewhat smaller than the total non-traditional mortgage market of 2006-2007.

While the absolute dollar amounts aren't quite at subprime crisis levels yet, the trajectory, structural characteristics, and potential for hidden leverage suggest this market could reach or exceed subprime in scale and systemic importance over the next several years. The key difference may be that this system is evolving more gradually and with somewhat more regulatory awareness.

Hedge Fund Leverage

Might as well start by again posting FRB-Cleveland Pres. Beth Hammack’s remarks

Trading Places: My New View from Inside the Federal Reserve (FRB-Cleveland)

A couple of financial market developments are on my radar: the considerable growth in private credit and hedge fund leverage.

A second area I am keeping an eye on is the surge in hedge fund leverage, particularly in US Treasury markets. … The top 10 hedge funds account for 40 percent of total repo borrowing and have leverage ratios of 18 to 1 as of the third quarter of 2024.

This just means that more capital is now attracted to Treasury basis arbitrage opportunities. Post-LTCM, I suspect most practitioners understand the risks of these positions.

Some studies have suggested that capital requirements led banks to reduce basis trading because of limits on their ability to lever up, a situation which might have encouraged hedge funds to pick up the slack.

What makes hedge funds of keen interest to financial stability policymakers is the important role they play in US Treasury market functioning. Hedge funds, through their arbitrage activities, support an efficient yield curve through US Treasury cash futures basis trades, asset swaps, and relative value trading. However, recent research has highlighted hedge funds’ basis trades as an emerging area of concern.

If highly levered entities such as hedge funds decide to unwind their positions, regulatory requirements may limit the market-making capabilities of dealers to facilitate this activity.

Makes sense.

Hedge funds hit back against new leverage limits (FT)

Bodies representing big hedge funds — including Izzy Englander’s Millennium Management, Ken Griffin’s Citadel, Paul Singer’s Elliott Management and Cliff Asness’s AQR — have attacked proposals by financial policymakers to limit how much leverage they take on and force them to be more open about it.

Prime Brokerage

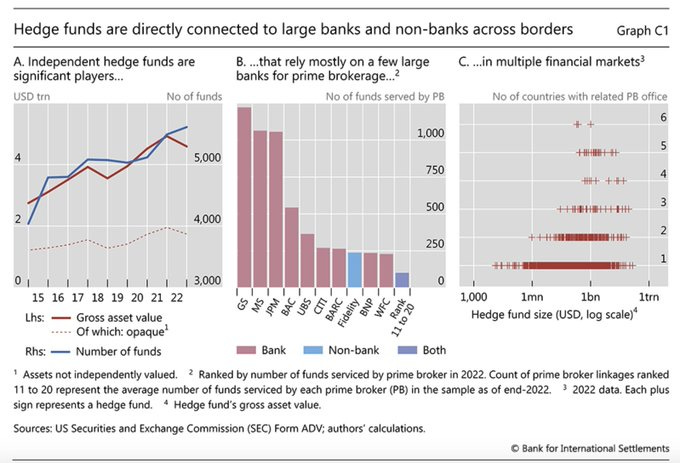

Of course, much of the current financial market environment is predicated on the effectiveness of bank’s prime brokerage businesses. This has been important since the 1990s, but has taken on even more importance post-GFC as risk exposures have increasingly been pushed out of the regulated banking sector while still being funded through the banks.

In that light, Rebecca Jackson of the Bank of England gave the following speech: Prime brokerage - speech by Rebecca Jackson. Noting the above evolution, she begins

[The Prime Brokerage] business [is] where growth improves margins, and whose growth makes it increasingly important for firms' bottom lines, and crucially, their balance sheet return and regulatory capital return metrics.

… last year we conducted a thematic review on the client risk disclosure standards applied by prime brokers, aimed at understanding existing practices across the industry, and to what extent the quality of counterparties’ risk disclosures directly influences firms’ risk appetite and the terms under which they are willing to do business.

What we hoped and expected to see, in a nutshell, was transparency, with a direct and verifiable relationship between the information that a client provides and the risk appetite that they’re allocated. But that’s not what we typically found. Instead, the information environment is rather foggy, with many firms generally falling short of the expectations around disclosure set in the aforementioned letters and guidelines.

… a disclosure score that is one of the many factors that can marginally affect a client's credit rating.

So: a large, complex and still fast-growing business, one that's highly international and interconnected; a business that may prove irresistible for new entrants and demands scale from existing ones; and a business that comes with exposures to some of the most sophisticated counterparties known to finance, but without the disclosures to match.

I guess I can add now that this is exactly the same thing we (NY Fed) found in the 1990s when we conducted a similar review. Some things don’t change, and likely won’t. The banks are chasing the business more that the HFs chasing the funding. And the long-entrenched players can and will be firmer on terms than the weaker new entrants looking to expand.

The prime broker–hedge fund nexus: recent evolution and implications for bank risks (BIS)