Perspective on Risk - July 8, 2023 (Liquidity)

Funding Liquidity; A Liquidity Trilemma; Higher For Longer Means Further Liquidity Pressures; FHLBs Are a Systemic Risk

Funding Liquidity

I came across an interesting (to me) post by Meyrick Chapman titled “These go to eleven!” on his ExorbitantPrivilege Substack. He looks at “the transaction volumes (velocity) of all the main cash securities (bonds and equities), transactions for Tri-party, DVP and GCF repo plus the main liquidity draining liabilities of the Federal Reserve (Reserve balances, ONRRP and Treasury General Account)’ and then performs some cluster analysis to analyze the results.

He clusters the various funding liquidity vehicles into three cohorts, segments into two time periods, and then looks at the trends of liquidity within each cluster. Clearly he is torturing the data quite a bit

He concludes:

US system-wide liquidity has shifted very significantly away from securities, including equities and towards HQLA repo. This change is associated with a pronounced increase in the Federal Reserve liabilities held in ONRRP facing money-market funds. That has meant the relative liquidity impact of Reserve balances has declined.

That said, the mean of Cluster 1 has bounced back to be close to zero, which suggests liquidity is currently stable, compared to the entire two year period. The liquidity injection made by the Fed following the bankruptcy of SVB (and others) contributed to this recent turnaround - though the breadth of securities market has become limited, which reflects lower liquidity.

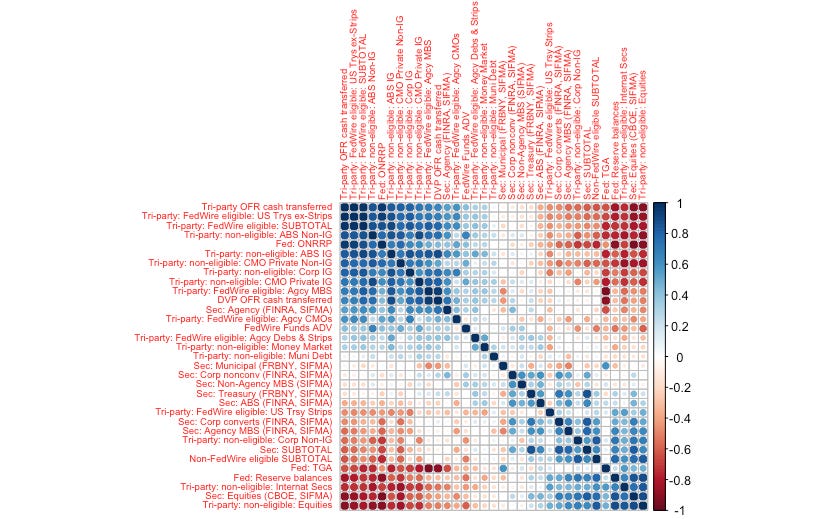

He further produces a correlation matrix that suggests bifurcated liquidity:

Markets that show transactions volumes increasing in line with ONRRP (including most repo markets, including DVP) and FedWire Funds service. These markets/collateral types are presented in top left of the chart.

On the other hand, most securities, including equities, repo for equities, repo for international securities, non-FedWire eligible repo have experienced relative transaction volume decline, concurrent with a decline in Reserve balances at the Fed.

A Liquidity Trilemma

Historical developments have highlighted a conundrum for policymakers.

Wealth inequality has increased the amount of large (uninsurable) pools of capital relative to (insurable) retail deposits

Supervisors and bankers generally prefer regulated banks to be funded with more stable retail deposits (rather than large uninsured ‘wholesale’ deposits).

As a result, more capital gets deployed outside of the regulated banking sector relative to capital deployed within the banking sector.

I was prodded to this simplification when reading Steven Kelly’s The Macro Story of SVB Isn't Just About the Fed on his Without Warning Substack.

Steven begins by highlighting this exchange during the House Financial Services hearing:

Rep. Scott: “Who made the decision to maintain this reliance on uninsured deposits—given the warnings also by our federal regulators? Who made this decision, Mr. Becker? This foolish, irresponsible, and deceitful decision—who made it?”

SVB’s Becker: “Congressman, as I said, that’s been our business model for as long as I can remember-”

Steven continues with two excellent paragraphs of his own:

Throughout his testimonies, SVB’s Becker regularly responded to questions about SVB’s proportion of uninsured deposits as he did above: with some form of “that’s how SVB has always done it.” Which… is actually the start of a really good explanation—but it’s of course horrible by itself. The “why” of this business model wasn’t just some bad management decision, it’s a macroeconomic result. SVB has always done it that way because that’s what the macroeconomics having a large innovation sector called for.

Much of the uninsured deposits questions from Congress, as in the example above, almost seemed to suggest that SVB just greedily decided against renewing an FDIC insurance policy for the rest of its deposits. Even the Government Accountability Office picked up on this suggestive language, saying, “SVB and Signature Bank relied on uninsured deposits to support their rapid growth.” As has now been well publicized, supervisors had at least noted the resultant risks, but failed to pursuantly rein the banks in.

I’ll skip the next section of his piece, where he thoughtfully covers SVB’s arguments that it was all the Fed’s fault.

Steven then makes the case that SVB’s business and comparative advantage begins with niche lending:

Lending to high-risk startups means you need a strong understanding of their cash flows.

And that the banking relationship was an incidental add-on that strengthened their overall ability to manage the risk.

Loans to investor funds often meant the startups that the funds invested in also had to bank with SVB. This is an understandable demand for visibility given the inherent risks in lending to the innovation economy. It also is a business model that means you end up with huge amounts of uninsured deposits—given the current structure of deposit insurance at least.

He concludes by asking the essential question, which goes to my trilemma; he essentially asks whether there is room within the regulated banking sector for a firm with this business model, whether it must be done outside of traditional banking, or whether there is some type of ‘hybrid approach.’ He suggests:

There’s probably a middle ground of killing some of the lending while the rest ends up being done by private equity, private credit, insurers, etc.

The problem with SVB was not the loans to startups. And it was not the sizeable uninsured liabilities. It was how the intermediary, SVB, used the liabilities to add duration risk, and it was the unrealized losses on the mortgage securities portfolio and the inaccurate regulatory measure of capital strength that did not account for these losses that is at fault. That is a failure of bank management, and a failure of bank supervision. And it was a failure on the part of regulators to impose losses on the funding providers, something more likely to happen (in a more gradual manner) in private markets.

Would things have been better it the activity was conducted outside of regulated banking? Perhaps. The uninsured liabilities would likely be invested in institutional money market funds that have much tighter duration limits. The lending would either be done by private pools of capital or through securitization.

This would avoid the problem of the correlation of assets and deposits seen within one singular institution. The cost of startup funding would likely be higher. There would be one less marginal buyer of longer dated mortgage securities, and that could have a marginal effect on the price of mortgage debt (but the funding of longer-duration assets is a wholly different problem). More intermediation would occur outside of regulators sights, and we’ve seen in the GFC the problems that this can cause.

Anyway, Steven’s post is worth a read, and his Substack is another recommended read (in this post-Twitter era of information diffusion).

Higher For Longer Means Further Liquidity Pressures

The yield curve has been inverted, we all know this. Initially, rising rates are a tremendous benefit to banks as they lag the market in paying interest on deposits and expand their net interest margin. However, over time this advantage disappears as consumers become more aware and sensitive to the opportunity cost of higher rates. Banks face the pressure of either paying higher rates, or losing core funding.

The problem also affects asset financing. An inverted yield curve means there is no positive carry on a number of assets. This pushes down prices for those assets.

The market has been forecasting a Fed reaction function that has them lowering rates rather quickly once rates peak. Conversely, the messaging from the Fed has been that rates will be held ‘higher for longer.’ As this occurs, the expectation of lower future rates will not materialize, and firms carrying these assets will face greater pressure to sell.

FHLBs Are a Systemic Risk

One of my earliest and deepest philosophical memories of my time at the NY Fed was the deep distain we had (believe it or not) for situations where there was private gain due to a public bailout or put option (‘moral hazard’ for those familiar with the term). At the time, perhaps the biggest concern was the two government GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fannie in particular had expanded its business considerably beyond the narrow conforming mortgage niche for which it was chartered. No tears were shed when it was nationalized in Sept. 2008 as one of many measures in the GFC.

A lesser, but always noticeable, concern was the Federal Home Loan Bank system. Congress established the Federal Home Loan Bank system in 1932 as a government sponsored enterprise to support mortgage lending and related community investment activity in the wake of the Great Depression. The original mandate of the FHLB System was to provide a reliable source of funding for thrift institutions (savings and loans) that lent money to homebuyers. This is back when we still had thrifts.

As with FNMA and Freddie, there is no explicit government guarantee, but there sure is an implicit one. And just like the mortgage GSEs, the FHLB system has expanded greatly beyond its initial mission: commercial banks, credit unions and insurers can now be members, and collateral requirements have loosened to allow the pledge of small business, small farm, and small agri-business loans as collateral for advances. To illustrate, about 20% of FHLB collateral is now backed by commercial real estate.

More importantly, many financial institutions use FHLB funding as a source of leverage, and the FHLB system has supplanted the Fed’s Discount Window as the primary lender during a time of crisis.

The FHLBs pose a systemic risk. The former regulator in me is encouraged that there may finally be some movement to rein in these guys.

US Regulator Considers Limiting Big Banks’ Borrowing From Backstop Lender (Bloomberg)

The FHFA started a review of the system in 2022. The effort has gathered more attention after the crisis this past March highlighted their expansive role.

A report on the review is expected by the end of September, FHFA Director Sandra Thompson told lawmakers in May. She has said it will include recommendations to Congress and changes the regulator itself can make.

FHFA considering recommending curbs on advances to big banks

Legislation passed in 1989 — in the wake of the Savings and Loan crisis — opened up access to the FHLBs to almost all banks and credit unions.

In addition to limiting access for big banks, regulators have discussed requiring banks that want to borrow from the FHLBs to hold a minimum percentage of their assets in mortgages

Here is a paper that addresses the FHLB system and financial stability; it is notable because former Fed Gov. Dan Tarullo is one of the authors.

Federal Home Loan Banks and Financial Stability

The Federal Home Loan Banks are the less well-known siblings of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Since these government-sponsored enterprises were created in 1932, changes in housing finance markets have rendered largely irrelevant their original purpose of increasing the availability of mortgages.

Yet the level and scope of their activities have increased dramatically in recent decades. These activities have at times both exacerbated risks to financial stability and obstructed the missions of federal financial regulators. Behind these undesirable outcomes lies the public/private hybrid nature of the FHLBs.

The private ownership and control of the FHLBs provide the incentive to take advantage of the considerable public privileges from which they benefit – including an explicit line of credit from the United States Government and an implied guarantee of all their debt similar to that enjoyed before the Global Financial Crisis by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This paper examines the past incidence and future potential for the FHLBs to amplify financial stability risks. It offers a framework for regulatory reform by the Federal Housing Finance Agency to contain these risks and avoid harmful interference with the activities of other federal regulators.

They go on to say:

We think the FHLBs present… a structural problem created by two circumstances: first, the hybrid public-private nature of the FHLBs and, second, the absence of a well-articulated contemporary purpose for FHLBs.

These factors create the potential for the FHLBs … to heighten risks to financial stability.

The ownership and control of the FHLBs are in private hands.

At the same time, the FHLBs enjoy very significant public privileges. Like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac before 2008, the FHLBs benefit from an explicit line of credit with the U.S. Treasury and from the market assumption of an implicit U.S. Government backstop for the FHLBs beyond that $4 billion statutory amount.

Troubles may arise either because of a conflict between private incentives and public goals or because the governmental privileges are incomplete and are more likely to reach their limit during periods of stress. The latter circumstance carries the risk that the increased, subsidized lending extended to FHLB members in normal times cannot be sustained just when they need it most.

The hybrid structure may also foster moral hazard if, as seems likely in light of the Fannie/Freddie experience in 2008, FHLB lenders and borrowers both assume that the Federal Reserve will ultimately step in to mitigate the stress associated with the limitations of the FHLBs.

The paper goes on to articulate the problems with the FHLB system:

We also explain why regulatory oversight of the FHLBs by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) may not take account of the ways in which FHLB activities affect the missions of other federal regulators.

{The paper] presents a number of examples of how the hybrid structure of the FHLB system has in the recent past contributed to systemic stress and undercut financial regulation.

Finally, I’d recommend those interested in this topic listen to Professor Katherine Judge on the Federal Home Loan Bank (Spotify link ’Forward Guidance’ podcast). She notes some interesting points:

The regulatory structure means that the Fed doesn’t pay (sufficient) attention to FHLB borrowing. Had they been closely watching FHLB advances they would have seen the developing regional bank liquidity needs. Same dynamic was observed in 2007/8.

The FHLBs initially help weak institutions by providing liquidity, but during times of stress, by increasing haircuts, they exacerbate problems.

FHLB advances take priority over FDIC claims due to their ‘super-priority’ status, increasing potential losses to the insurance fund.

The biggest banks are the biggest beneficiaries.

Limiting FHLB lending to any one institution would have forced SVB and Signature to the Fed Discount Window earlier, providing an opportunity to resolve sooner at a smaller loss.

It will never happen, but the FHLBs should be designated as systemically important financial institutions (SIFI) and subject to Fed supervisory oversight. Or someone should send in Tim Clark (IYKYK).