Perspective on Risk - August 23, 2023

Hubris and Leverage; The Future Financial System; China; Correlation, and Synchronization In Collective Systems; Happiness

Hubris and Leverage

LTCM: 25 Years On (Net Interest)

A defining moment in 1990s finance.

“LTCM’s experts start with an academic research framework and quantitative orientation to build and refine models and to put concepts into practice on a large scale,” the firm’s marketing materials note. Its brochure describes LTCM not as a fund but as a “financial technology company.” (A red flag if ever there was one.)

The Future Financial System

Some History of Non-Bank Money

An interesting historical article by Daniela Gabor of UWE Bristol. She goes through some of the history of the dealer call market, which was an early form of a type of repo between banks. She argues that:

The alchemy of (shadow) banking is the alchemy of monetary time — of ordering time in balance sheets to create new forms of money that credibly promise par convertibility on demand

Much of this resonates with me as it aligns with Gerald Corrigan’s seminal Are Banks Special?

Shadow money without a central bank (FT)

Par convertibility into state-backed money is critical to moneyeness (as SVB depositors recently learnt). But state-backing, as the late Victoria Chick once noted, is expensive.

In return for deposit guarantees or a lender of last resort, the state imposes regulations that constrain profitability. That triggers repeated efforts to invent new forms of money that can credibly store value without the state. And time is the key ingredient. Money creators are time entrepreneurs that experiment with the temporal horizons of their pledges to construct par convertibility in the process of financing credit assets.

Repurchase agreements, IOUs backed by collateral securities. These become shadow money through daily collateral valuation — mark-to-market of collateral portfolios and margin calls — that preserves par convertibility between the repo IOU and the market value of collateral securities.

The fragile day order that characterises money in market-based finance — then and now — requires policy interventions that preserve the market value of collateral securities. Such interventions include central banks’ adoption of market-maker of last resort after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, or the US Federal Reserve’s recent turn to par-value lender of last resort with the Bank Term Funding Program. The BTFP is revolutionary in that it extinguishes time from collateral valuation, once a fundamental tenet of crisis central banking.

As Corrigan, though, noted, all liquidity risk ultimately comes back to the banking system as banks “are the backup source of liquidity to all other institutions, financial and nonfinancial.”

Fed’s Recognition of Non-Bank Finance

Excellent post by Paul Davies on the (late) recognition of the shift to non-bank lending

How the Fed Got Drawn Into the Shadows (Bloomberg Opinion)

Proposed new rules recognize the pivotal economic role of hedge funds, private equity and private credit

The evolution of capital rules since the 2008 financial crisis has been focused on making the banking system stronger, safer and less likely to need bailouts. The supply of credit from financial markets instead has ballooned partly as a consequence of this. But pushing risk from banks into what’s often called shadow banks hasn’t necessarily made the system as a whole safer, nor has it reduced the Fed’s role in lending support when times get tough.

In fact, the Fed formalized its job as the lender of last resort to the shadow banking system – or what could be called dealer of last resort – after seeing the problems that emerged during the dash for cash at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and when money markets seized up in September 2019.

These changes have given primary dealers, which handle government debt trading, and money-market funds access — either directly or through dealers — to the sort of central bank deposit and borrowing facilities that traditional banks have always had in modern finance.

What central bankers and regulators realized in 2008 and had reinforced for them even more in 2020 is that the shadow banking system can suffer chaotic and destructive runs just like traditional banks.

Part of the reason shadow banking grew so large, according to the money-market specialist and former Credit Suisse Group AG analyst Zoltan Pozsar, is that companies and foreign central banks with large amounts of dollars couldn’t safely keep their cash in banks: Deposit insurance only stretches to $250,000, and there aren’t enough big, safe banks to spread it around.

China

Policy

Bill Bishop on the Sinocism site publishes a speech from John Garnaut. I’d add this to the “must read” list if you want to understand China. Engineers of the Soul: Ideology in Xi Jinping's China by John Garnaut. The quote that sticks with me is:

Today the PRC is the only ruling communist party that has never split with Stalin, with the partial exception of North Korea.

Counterpoint to Recent Predictions of Gloom & Doom

I’ve been a bit surprised how much the popular press has jumped on the China Crisis story. For instance the WSJ’s China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over. What Comes Next?

For decades, China powered its economy by investing in factories, skyscrapers and roads. The model sparked an extraordinary period of growth that lifted China out of poverty and turned it into a global giant whose export prowess washed across the globe.

Now the model is broken.

Nick Lardy, longtime China watcher, argues that the concern is premature (and in some cases wrong). Lardy has frequently been on this side of arguments.

How serious is China's economic slowdown? (Peterson Institute)

A new consensus has emerged among many economists, journalists, and other analysts regarding the current slowdown in the Chinese economy. Their contention is that China's stumbles in spring 2023 portend a far more serious long-term problem derived from flawed, insular, and Communist Party-controlled policymaking in response to COVID and its aftermath, with likely adverse consequences for the global economy.

That widely popular assessment is likely premature and, at least in part, perhaps simply wrong.

China and its people suffered greatly during the COVID pandemic, both in terms of lives lost and economic output foregone. The analysis above suggests that economic recovery may have begun. But it is fragile. Time will tell whether recovery takes hold or whether China is falling into a cyclical downward spiral.

Correlation, and Synchronization In Collective Systems

A Century of Global Equity Market Correlations

In this paper, we use a unique long-run dataset of regulatory constraints on capital account openness to explain stock market correlations. We argue that changes in the co-movement of indices have not been random. Rather, they are mainly driven by greater freedom to move funds from one country to another. We examine this pattern systematically for the last century, and find it to be most pronounced in the recent past. We conclude that greater [capital account] openness has been the single most important cause of growing correlations during the last quarter of a century, though increasingly correlated economic fundamentals also matter.

I remember when we all believed that different regional US housing markets were weakly correlated. National banking and the rise of large non-bank pools of money could be thought to have driven that risk in correlations as well.

Empirical evidence on the stock-bond correlation

Our empirical evidence points to inflation and real returns on short-term bonds, and the uncertainty surrounding inflation as important factors for understanding the sign and magnitude of the stock-bond correlation. Our historical analyses across countries suggest that our findings are robust. We apply these insights to analyze the implications of a shift in stock-bond correlation regime for the risk of multi-asset class portfolios and for bonds risk premia.

Our historical data starting in 1875 indicates that a positive stock-bond correlation has been more common than a negative one, even though the latter has been observed mostly in the past two decades. Our overarching finding is that for the post-1952 period with independent central banks, a positive stock-bond correlation is observed during periods with high inflation and high real returns on Treasury bills.

Our empirical results show that bond risk premiums solely derived from the term structure of interest rates are positively related to those based on the CAPM and therefore derived from the stock-bond correlation. This may be some indication that the CAPM has a stronger empirical basis across than within asset classes

New Proof Shows That ‘Expander’ Graphs Synchronize

I don’t know if this is ultimately related or not, but I read it concurrently with the aforementioned paper.

Expander graphs are special types of networks which are sparse but also well connected. Bandiera proved that synchronization is inevitable in expander graphs. Spontaneous synchronization is a phenomenon in which oscillators, which might take the form of pendulums, springs, human heart cells or fireflies, end up moving in lockstep without any central coordination mechanism.

There’s probably only one or two of you who will be interested in graphs, but here it is.

Happiness

The Socio Political Demography of Happiness

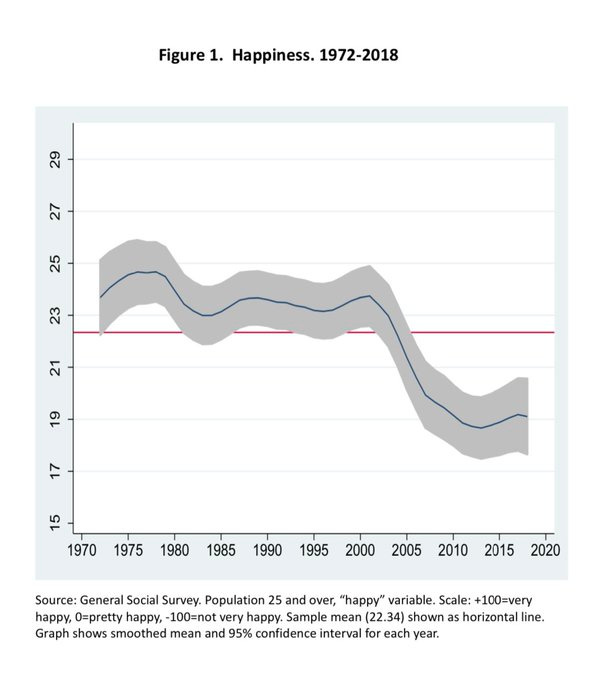

Since 1972 the General Social Survey (GSS) has asked a representative sample of US adults “… [are] you …very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” Overall, the population is reasonably happy even after a mild recent decline.

Being married is the most important differentiator with a 30-percentage point happy-unhappy gap over the unmarried.

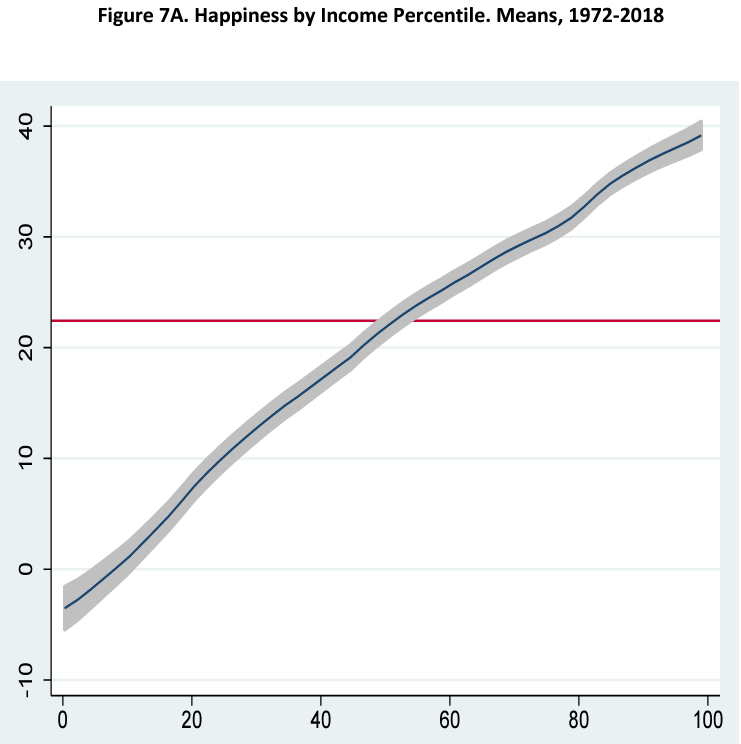

Income is also important, but Easterlin’s (1974) paradox applies: the rich are much happier than the poor at any moment, but income growth doesn’t matter.

Education and racial differences are also consequential, though the black-white gap has narrowed substantially.

Geographic, gender and age differences have been relatively unimportant, though old-age unhappiness may be emerging.

Conservatives are distinctly happier than liberals as are people who trust others or the Federal government.